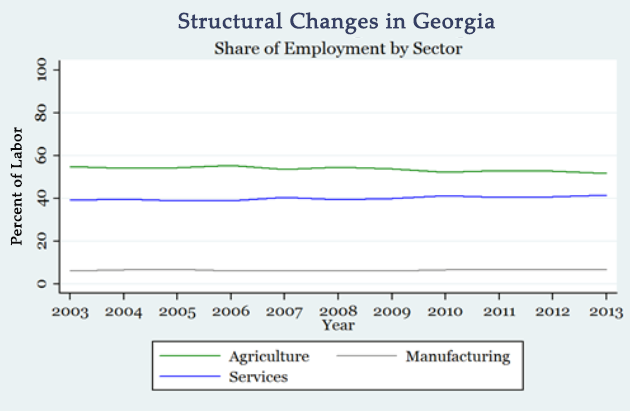

Any observer of the Georgian economy would probably agree that the country has too many people employed (or, rather, under-employed) in agriculture. Historically, many countries have experienced a secular decline in the share of employment (and GDP) related to the agricultural sector. Yet, Georgia has seen limited structural change out of agriculture (other than, perhaps, into seasonal or permanent labor migration). For more than a decade, the share of employment in the agricultural sector has been around 52-54%. As illustrated in the figure below, the remainder of jobs were in the services sector, with scarce few in manufacturing. What we observe is therefore a persistently high share of employment in a low productivity sector.

STRUCTURAL CHANGE (OR THE LACK THEREOF) IN GEORGIA

The notion that too many Georgians are stuck in agriculture was a central tenet of the Saakashvili government reform agenda. An argument has often been made by Georgian politicians at the time that “no developed country has more than 3-4% of its workforce in agriculture.” The conclusion drawn from this (correct) observation was that, in order to develop, Georgia has to go through a rapid process of land consolidation and urbanization. Hence, projects such as Lazika, miniscule agricultural budgets and neglect of agricultural policy. When subsidies started being thrown at rural dwellers in 2010-2012, it was done for purely political reasons.

Yet, perhaps paradoxically, agriculture is today one of the fastest growing sectors in the Georgian economy, encouraged, on the one hand, by the re-opening of traditional export markets in Eurasia, and, on the other, a spate of government and donor initiatives seeking to complete land registration and start an effective land market, repair rural infrastructure, improve skills and provide cheap finance and other services.

This recent development begs the question – in line with the great ISET Economist tradition of thinking about potential growth sources for Georgia – whether or not agriculture (and related food processing) could serve as an engine of job creation and inclusive economic development for the country.

SEARCH FOR A NEW DEVELOPMENT MODEL

A recent thought-provoking piece by Dani Rodrik ("Are Services the New Manufactures?") discusses whether developing countries need a new growth model. As argued by Rodrik, “export-oriented industrialization, history’s most certain path to riches, may have run its course.” On the one hand, he writes, “manufacturing today is not what it used to be. It has become much more capital- and skill-intensive, with greatly diminished potential to absorb large amounts of labor from the countryside.” On the other, China’s success makes it much harder for many other countries “to establish more than a niche in manufacturing.”

Now, while urban services are constituting a very large and increasing share of GDP in many developing nations, Rodrik is skeptical as to their potential to “deliver rapid growth and good jobs in the way that manufacturing once did.” His skepticism stems from two observations.

Banking, finance, other business and ICT services are certainly high-productivity activities that can help lift economies with an adequately trained work force. However, in most developing countries such internationally demanded (“tradable”) services cannot absorb more than a fraction of the labor supply.

Other types of locally demanded (“non-tradable”) services, such as retail trade, hairdressing and taxi driving can certainly absorb excess agricultural workers, yet, jobs in these sectors do not promise a lot of productivity gains.

Moreover, argues Rodrik, any growth in low productivity non-tradable services is ultimately self-limiting. His point becomes evident if one cares to analyze the taxi service market in Tbilisi. As more and more villagers started driving taxis in Tbilisi, taxi fares went down to a level only slightly above earnings in the low-productivity agricultural jobs, therefore reducing or completely eliminating the incentives for the arrival of new drivers (and their shoddy Ladas).

For this very reason, micro-lending institutions, such as (most famously) the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, often become victims of their own (initial) success. Micro-financed enterprises, e.g. providers of cellphone services in remote villages, tend to go out of business once the number of identical enterprises hits a critical threshold and the fees they could charge collapse. The result is bankruptcy for both lenders and borrowers.

WHY NOT AGRICULTURE?

Why might the agricultural sector serve as a potential growth engine in Georgia? One reason is that Georgia does not have too many other options. As the country has learned the hard way, manufacturing and services startups are not easy to sustain in an open global economy of today, particularly in the absence of a skilled and disciplined workforce.

But there are many ‘positive’ reasons for agriculture to serve the locomotive function.

First, while some might view the agricultural sector in Georgia as more of a safety net for hundreds of thousands of under-employed individuals, this is the sector where a lot low-hanging fruit remain (both figuratively and literally). In other words, productivity gains would be relatively easy to achieve with very modest financial investment, through improved organization and processes.

Second, it’s worth considering that many economies in East Asia achieved their high rates of growth by first experiencing development of their agricultural sectors. Increases in agricultural productivity fed into further investment in light manufacturing in urban areas and both the ‘labor push’ and ‘labor pull’ effects went into full force (see “Agriculture and Structural Transformation in Developing Asia: Review and Outlook” for more). While, as Rodrik points out, export-led industrialization might be a challenge for countries like Georgia, the economic boon arising from increased agricultural productivity may induce the development of other industries (including those which we cannot predict ex ante).

Third, when looking at global trends, there seems to be increasing demand for differentiated agricultural products (both primary and processed). Just look at microbrewery startup rates in the United States, agritourism or the slow food movement in Italy, etc. With its multitude of soil and climate conditions, unique culture and traditions, there is great potential for Georgia to generate unique, high value, geographically denominated products and engage in innovative agroprocessing and organic farming.

Fourth, and very significantly, gradual commercialization of smallholder surplus production can be one avenue for lifting people in rural areas out of poverty and ‘readying’ them for functioning in a modern exchange or money economy. As Peter Bauer argued in Dissent on Development: Studies and Debates in Development Economics (1972):

There are various reasons why in many poor countries a large measure of continued reliance on agriculture, notably on agricultural production for sale, is likely to represent the most effective deployment of resources for the promotion of higher living standards. One reason is the familiar argument based on comparative costs. Another, less familiar, reason is that production of cash crops is less of a break with traditional methods of production than subsidized or enforced industrialization. Agriculture has been the principal occupation in most of these countries for centuries or even millennia. Thus in the production of cash crops the difficulties of the adjustment of attitudes and institutions in the course of the transition from subsistence production to an exchange or money economy are not compounded by the need to have to acquire at the same time knowledge of entirely new methods and techniques of production. After some time spent on the cultivation of cash crops, people find it easier to get used to the ways, attitudes and institutions appropriate to a money economy. This greater familiarity with the money economy facilitates effective industrialization. In these conditions of transition from a subsistence to a money economy, conditions widely prevalent in poor countries, production of cash crops and effective industrialization are complementary through time. The unfavourable contrast often drawn between agriculture and manufacturing, to the detriment of the former, is an example of a time-less, unhistorical approach to economic development, an approach which is inappropriate to the historical development of societies.

Bauer wrote in a period characterized by the “Green Revolution”, when productivity in agriculture grew at unprecedented levels. This might explain his optimism and his strong support for the introduction of cash crops as a way to foster development. While the experience of many countries shows that investing in the mass production of cash crops does not necessarily lead to success, Bauer’s ideas remain valid in a broader sense.

BUT NOT JUST ANY TYPE OF AGRICULTURE

Agriculture has a great development potential and, as stated above, differentiation in agricultural production and related agribusiness activities (rather than homogenization and mass production) is driving currently some of the most interesting success stories in agriculture around the world. In a globalized world, where mass products can easily be reproduced – at ever decreasing costs, driving profit margins to zero – well-trodden paths do not show much promise anymore. What matters is what cannot be easily reproduced or copied. Georgia and other developing countries should try new tricks, building on their own strengths and on what makes them unique.

Luckily for Georgia, the country’s history, culture, biological diversity and agricultural tradition put it in the condition to do much better than just import some “modern” high yield crop and engage in large scale (capital intensive) agricultural production of standardized agricultural products. Georgia can carve its niche in the high value added (more labor intensive) segment of the international markets, turning its weaknesses (such as abundance of labor force in the countryside) into a strength.

Crafting appropriate policy instruments to support the agricultural sector is a challenging endeavor, and much more analysis must be conducted ex ante before launching any new policy initiatives. Taxing the private sector only to subsidize potentially unproductive activities in agriculture is surely something to be avoided. That said, we are certain that Georgia’s agriculture can play the role Bauer suggested back in 1972, and be a key to the country’s long-term inclusive development.

Special thanks to Giorgi Kalakashvili at the National Statistics Office of Georgia for providing data about employment by sector.

Comments

Unfortunately, according to Geostat, growth in the agricultural sector in the first two quarters of 2014 has been stagnant and lagged every other sector; only 1.2%, disappointing compared to the 11.3% growth in the first two quarters of 2013. Processing industry, on the other hand, has shown double-digit growth most years since 2010.

http://factcheck.ge/en/article/as-of-today-tourism-is-the-only-sector-in-our-economy-showing-growth/

Industrial employment not surging correspondingly over the past four years might be attributable to training and investment in modern equipment paying dividends in worker productivity.

The East Asian model of enhancing productivity in all segments of the agriculture sector (corporate, SME and smallholder) by stimulating linkages between the segments, while aggressively encouraging urbanisation and industrialisation via attractive tax concessions for labour-intensive manufacturers, has worked relatively well; more people have been lifted out of poverty in the past three decades than at any other time in human history as a result. The processing trade on Georgia's Black Sea Coast is doing quite well, mostly in the garment sector, and has huge potential if positive Turkish investor sentiment can be cultivated. Matching the incentives that rival manufacturing FDI destinations offer is needed if manufacturing is to absorb labour displaced by increased farm labourer productivity. Urbanisation and consolidation of agricultural holdings is an inevitable trend in a growing economy. In Georgia, a balanced policy is needed, devoid of romantic rural utopianism or active neglect of promising agricultural sectors.

True, though given that much of the economic activity taking place in the agricultural sector is informal and unreported (or under-reported), it's difficult to say for sure.

I think that's part of the puzzle - that urbanization and consolidation of agricultural holdings have taken place in most growing economies, but that these trends have not been observed in Georgia (which again might be due to data limitations). This may indeed be due to limited linkages between smallholder farmers, SMEs, and agriprocessors..

Consolidation of land holdings is hard when a large proportion of landowners of small plots live in Moscow, Tbilisi or Istanbul. Even for local villagers, contacting remote landowners with a purchase offer on their plot is very difficult. It is also very hard when over 70% of farmland has no formal title yet. Suspension of farmland privatisation also has impeded farmland consolidation. Exempting smallholders from paying land taxes may be compassionate considering how vulnerable many smallholder households are, but an unintended consequence is that it reduces the incentive for absentee small-plot landlords to sell off fallow land that more active neighbours might want to acquire and bring into production. Choking off capital for consolidation by banning foreign capital from involvement in farmland acquisition also dramatically slows down the process; instead of accessing billions of dollars in capital from abroad, local entrepreneurs must rely on a tiny pool of wealthy individuals in Tbilisi as equity investors, or turn to local banks who place a big discount on the market value of the land when calculating collateral and charge high interest rates.

An excellent piece!

I would like to elaborate further in regarding the correlation between agriculture modernization and employment.

• The asseveration by the previous Georgian government that no developed country has more than 4% of its workforce in agriculture was highly inaccurate. In 13 out of the 27 EU member States (all of which are developed countries) the working force in agriculture is above 4% including in countries such as Austria!); and in 5 of them, it is even above 10% (Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Greece and Portugal). For more background on agriculture labour statistics in the EU: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/rural-area-economics/briefs/pdf/08_en.pdf

• The production in agriculture employment in all modern economies was (and still is) a gradual process that in most countries took many decades. I really doubt if Georgia will ever have just 4% of its working force agriculture, but even if so, I think it is obvious that the process will require many, many years, so before thinking on unrealistic hypothesis as if Georgia one day soon would become like the Netherlands (which was probably the only understanding of European agriculture that Shaakhasvili had), it would be perhaps better see what has happened in those countries with more relevant backgrounds to the local context here.

• Poland, with a very vibrant, modern and diversify economy is not a bad example case of were Georgia would like to be in a not too distant future. To reach Poland's wellbeing levels is indeed much brighter future than, let's say, to become like Bulgaria: Poland's per capita GDP is roughly 50% higher than Bulgaria's. Well, 19% of the Poles work in agriculture, while in Bulgaria it's only 6%. The correlation between wealth of the nations and percentage of people in agriculture is sometimes paradoxical.

• The reform and modernization of the agriculture sector that has taken place in Europe countries has indeed, reduced the number of jobs in primary production, but has in parallel augmented the employment in the food sector, which is currently the leading manufacturing sector in Europe in terms of jobs (15%) . The food industry features in the top 3 manufacturing activities in terms of turnover in several EU Member States and ranks first in France, Spain, the UK , Denmark and Portugal.

• We have to add the expansion of jobs in the agriculture supply industry (e.g. agriculture equipment manufacturers, fertilizers industry and so on) and the agriculture-related service sector activities (e.g. veterinarians, farm accountants, agro marketing sector…and so on!). All of these jobs are dependent on the agriculture sector. It is estimated that for every farmer in Europe, there are on average another two jobs.

• To sum up: A modern agri-food sector requires less people farming, but needs more people doing many other activities along the value chain. This is the very point that the previous government (which its lack of understand of modern agriculture) never fully grasped. This extra new jobs may normally cannot fully compensate the job destruction in primary production but a sensible analysis of the effects of agriculture modernization in the labor market shall consider its effects in the other industries too.

• Besides this direct job creation in other sectors, the modernization of the agriculture means more and better production and thus better income for the (fewer) farmers which will them have better purchasing power. That also indirect creates jobs.

• When a country modernizes its agri-food sector, there is indeed a destruction of jobs in primary production, but also a creation of other kinds of jobs. If a country keeps large parts of its population (under) employed in a noncompetitive agriculture, at best it will keep that portions of the society at poor levels of subsistence, and at worst the destruction of farming jobs will happen anyway, and at higher speed (due to inability of the farmers to compete) and without those other new direct and indirect jobs along the value chain that the modernization of the sector could have brought.

Another gross miss-conception still well spread in Georgia is that the modernization of agriculture will inexorably produce massive migration to the cities. Well, people normally move seeking for better jobs and living standards. If jobs are destroyed in agriculture and no alternative jobs are provided (and no social and leisure infrastructures are developed) in the villages and small towns, indeed people will migrate to wherever better job opportunities exist (i.e.to the cities or abroad). So the whole issue here regards to what policies (if any) will be developed to channel private and public investments to the rural areas.

In most European countries, the percentage of population living in the rural areas has not changed significantly even if the percentage of people working in agriculture has constantly declined. In Spain, for instance, 18% of the working population was in the agriculture sector in 1980. 30 years later, in 2010, only 4% was employed in agriculture. Someone could expect that such massive reduction of agriculture employment generated massive villages-to-cities migration. Well…not really: In 1980, 75% of the Spaniards were living in the cities, whereas in 2010… they were 77%, i.e. just a minimal augmentation.

Spain has almost as many people in its villages as 30 years ago…despite having only less than a fourth of the number of farmers that the country used to have.

Most rural areas in Europe are not mainly dependent in agriculture anymore, because the economic fabric of the villages is now highly diversify and citizens have similar opportunities of wellbeing (access to health care, fine education and so on) –whether they live in Madrid or in some small village somewhere in the countryside of Andalucía.

Fewer jobs in agriculture will not necessarily mean killing the village life… it all depends on how policies are shaped.

Dear Juan, many thanks for your comments. I only want to re-iterate one point you've made: for Georgia to become a modern country it should really make sure that its villagers have much improved access to education (particularly pre-school and elementary school levels). The healthcare situation and many other things needs fixing as well, but elementary education is the key for social change.

This is far from being about formal 'teacher qualifications', 'education standards' and 'textbooks' - something all Georgia's ministries of education have been preoccupied (obsessed?) with so far.

This is about changing the children's role models. How do you achieve that? Only by bringing new teachers into the classroom. Individuals who are committed to education, come to class on time, prepare for classes (do their own homework!), don't litter the environment, know something about the world outside the village. Georgia needs not 'teachers' but leaders in education!

There are plenty of successful examples since many developing countries around the world have tried achieving the same feat. Even Georgia itself has had huge successes in bringing light to the country's darkest corners. In the 19th century, under Ilya Chavchavadze's leadership, and in the early Soviet period, as part of the general drive to eliminate illiteracy.

Along with points above, I would like to highlight the demographic situation in Georgian agriculture. Georgian farmers are ageing. According to the Agricultural census of 2004, persons 55 and over operate 54.7% of all agricultural holdings, and another 20.9% is operated by persons from the 45 to 54-age bracket. Today these people, who are over 55 and over 65 years old accordingly, will leave the sector. At the same time, youth tend to neither stay in the village nor work in agriculture. Moreover, due to low productivity and income afforded by agriculture farmers are encouraging young from rural areas to migrate to cities for a better future. Who will fill the gap? There is a possibility to restructure Georgian agriculture and ensure higher standards of living in rural areas and increase of commercially oriented farms through accurate development policy.

Along with points above, I would like to highlight the demographic situation in Georgian agriculture. Georgian farmers are ageing. According to the Agricultural census of 2004, persons 55 and over operate 54.7% of all agricultural holdings, and another 20.9% is operated by persons from the 45 to 54-age bracket. Today these people, who are over 55 and over 65 years old accordingly, will leave the sector. At the same time, youth tend to neither stay in the village nor work in agriculture. Moreover, due to low productivity and income afforded by agriculture farmers are encouraging young from rural areas to migrate to cities for a better future. Who will fill the gap? There is a possibility to restructure Georgian agriculture and ensure higher standards of living in rural areas and increase of commercially oriented farms through accurate development policy

When properties are effectively consolidated, and labour productivity rises to international norms due to training, mechanisation and a cadre of fitter, younger workers, the entire Georgian food and agriculture sector will not require a very large workforce. A pool of 300,000 well-trained, well-equipped, well-motivated workers and landowners would be enough to operate the entire agri-food sector on 100% of available farmland and grazing land, including deep processing, logistics and service industries, to a level where Georgia imported no foodstuffs other than wheat, and exported five times as much fresh produce and wine as it does now. At that level of productivity, wages and salaries could be on par with European norms while still being cost-effective for employers. For the other 800,000 people in the countryside of working age, viable occupations in non-agrifood enterprises like tourism, logistics or light industry in villages, regional towns or new cities must be considered as an imperative for development. To think more boldly, Georgia needs to create such a dynamic service sector and manufacturing industry as to attract many of the 1.5 million Georgians living abroad to return home and rebuild their motherland, with agriculture, light industry and the service sector as the pillars of this success.