Wages and productivity levels differ across countries. For instance, in 2011 the average yearly income in the US was about $53 000, whilst the same indicator was $250 in Madagascar. Clearly then, Madagascar has a competitive advantage in labor cost over the US. But the issue is not so simple because workers in the US operate in a completely different environment (with better capital facilities, more educated colleagues, higher level of technologies, etc.) that determine a much higher productivity level. Higher wages can positively affect productivity in an economy. However, at the same time the opposite can also be true.

The unit labor cost (ULC) is an important macroeconomic variable for an economy. It measures the average cost of labor per unit of output. In general, costs are essential concepts in terms of competitiveness because they have common determinants such as taxation, input prices, productivity (efficiency), and regulatory and environmental measures. Therefore the ULC is a measure of cost/price competitiveness. ULCs are defined as a ratio of a worker’s total compensation to labor productivity. They positively depend on a worker’s compensation (nominal wages) and they are negatively correlated to labor productivity. The labor productivity itself depends on the following factors: new technologies, investments and savings, and human capital. At the macro level, increasing productivity and reducing ULCs (which is associated with economic growth) is not an easy task because this does not happen overnight. The ULC is mainly used to assess a country’s competitiveness at the global level, explain price developments within an economy, and evaluate export opportunities in a given industry. Lower ULC is also considered as a contributor of income through exports.

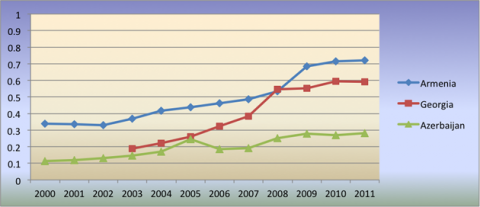

Figure 1. Unit Labor Costs (rescaled) for Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan

There are different methodologies for calculating ULCs. In this investigation, they are computed as a ratio of hourly compensation to productivity. It also should be noted that compensation is expressed in current prices. As for labor productivity, it is given in constant (real) prices.

Figure 1 shows the dynamics of development of the unit labor costs for Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan over time. As it can be seen from the graph, in 2011 Azerbaijan had the lowest ULC among these countries. This can be explained by the fact that Azerbaijan gets a huge amount of financial resources from the export of oil products (the share of oil products is 92% of total exports), while the industry directly employs only a small percentage of the workforce – close to 7%. As a result, the productivity in the oil sector is high, whereas the overall ULC in Azerbaijan is low. As for Georgia and Armenia, they have had relatively similar developments of the ULC over time. Georgia has a competitive advantage over Armenia in terms of unit labor costs. It should also be highlighted that the ULC has been constantly increasing over time in both Georgia and Armenia, which means that workers’ nominal compensation grew faster than labor productivity. As for Azerbaijan, it managed to keep the ULC relatively much less volatile. I think that the last fact basically stems from the tendency, at the macro level, for labor productivity to be increasing very fast (mainly caused by the high growth in oil production). It should also be mentioned that the relatively constant ULC of Azerbaijan indicates equal rates of growth of workers’ nominal wages and labor productivity.

In 2007 Georgia experienced a sharp increase in nominal wages that caused the unit labor cost to rise. The increase in productivity mitigated and obscured the rising cost of labor in Georgia, resulting in only a modest increase in unit labor cost. As a consequence, according to this measurement, the competitiveness of Georgia considerably worsened during the 2006-2008 period. In addition, it should be underlined that the high growth rates of the ULC could be a significant contributor to the high inflation in the country over this same period (8.8%, 11.0% and 5.5% in 2006, 2007 and 2008respectively). As a result, high inflation (pushed by higher ULC)could cause an increase in imports (domestic goods became more expensive on the international markets) and raise the trade deficit.

The comparison of the ULC measures for Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan gave us the following results: Azerbaijan has a significant competitive advantage over Georgia and Armenia, mainly caused by the rapid growth in labor productivity pushed by the high growth rates of oil production. Georgia is more competitive than Armenia in terms of unit labor costs. Furthermore, unit labor costs can be used to explain inflationary processes in a country. In order to increase the competitiveness of a country, it is necessary that the growth rate of labor productivity be higher than the growth rate of worker’s compensation. But it is still questionable whether these measures give us a realistic picture about the situation of competitiveness issues in these countries. The following very relevant questions can still be raised: Is the unit labor cost a perfect measure in assessing the competitiveness of a country? Does a higher ULC truly reflect the loss of competitiveness? What are the factors that caused high growth rates in the ULC in Georgia within the period 2005-2007? Why did the ULC in Armenia rise significantly in 2009? What were the reasons for a decline in the ULC in Azerbaijan in 2006? Why has the growth rate of Azerbaijan’s ULC grown so modestly over time?

Comments

Some of these statements and figures would need a deeper explanation (even just to answer to the questions you are raising). For example: would it be possible to know exactly how productivity has been calculated, whether compensations have also been converted in costant (real) prices and whether this has been done using a comparable methodology? Moreover, would it be possible to estimate the trends in the non-oil sector of Azerbaijan? Before clarifiying all these (and maybe other) aspects, every statement is potentially questionable.

While Turkey is our main trade partner, it would be very interesting to assess the ULCs compared to Turkey as well.

There are different methodologies for calculating ULCs. In this investigation, they are computed as a ratio of hourly compensation to real productivity. Compensation is expressed in current prices. As for labor productivity, it is given in constant prices. Labor productivity in real terms is measured as a ratio of real output to hours worked per year (1920 in this case).

I am not sure whether it is possible to estimate trends in non-oil sectors of Azerbaijan. Anyway I think it is a good idea.

I think every statement can be potentially questionable in macroeconomics because there is no such thing as a perfect measure.

Question to NP: What do you mean in comparable methodology?

I was referring to the conversion of remuneration in current prices to remuneration in constant prices. In case it had been performed, I was wondering whether the same deflator had been used.

Going back to the post, I am not sure it is wise to calculate ULC dividing nominal compensations by real labor productivity. This, for example, risks to show patterns that might be just due to differences in the country inflation rates. If you are interested in measuring ULC trends it might be interesting to take real values both at the numerator and at the denominator.

Another thing. Are numerator and denominator expressed in the same currency? If so, in local currency or foreign currency?

If you are interested in the impact of ULC on the competitiveness of exports, you should then include in the analysis an indicator that takes into account the exchange rate (maybe have everything numerator and denominator in constant dollars?). Looking at the exchange rate is crucial to see whether or not an increase in nominal wages (in local currency) automatically translates into a loss of competitiveness.

It is a very interesting article.

It would be great to see industry-by-industry breakdowns of ULC, for agriculture, mining/oil& gas, manufacturing and service industries.

The ratio of real wages to real productivity is a different measure of labor costs which is called real unit labor cost (RULC). Actually these measures can also be calculated for Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. But they need further search and investigation (more data, calculations like deflating wages/compensation). In my opinion it would be interesting to calculate them also and compare but I doubt that a comparison of the RULCs would change the overall picture considerably.

Both numerator and denominator are in the same (local) currencies.

I think Azerbaijan has not a significant competitive advantage over Georgia and Armenia. Simple calcualtion proves this. 93% of work force of Azerbaijan is working in the non-oil sectors, such as Agriculture, service and others.If we divide the amount of production to this high number of people, we will get lower productivity. This lower productivity will increase the level of ULC for the non-oil sectors tremendously in Azerbaijan. And it shows that Azerbaijan have not competitive advantage in the non-oil sectors over Georgia and Armenia. I think you should calculate the level of ULC for each sector and then compare which countries have competitive advantage in the certain sector.it will give more proper comparison and insight.I think it is not good idea to compare the levels of ULC for whole production. Azerbaijan has a significant competitive advantage in the oil sector over Armenia and Georgia and the reasons are quite clear I think

I suggest that inflation is driving ULC measured by described methodology rather than opposite. It will be interesting to compare ULC with inflation and printing money(as primary source for inflation). I guess this will explain fluctuations questioned at the end of the article.