In his blog post “The puzzle of agricultural productivity in Georgia and Armenia” , Adam Pellillo raises the following question:

Georgia seems to be the only former Soviet republic in which agricultural productivity hasn’t returned to or exceeded its level in 1992. As of 2010, agricultural productivity stood at only 77 percent of where it was at nearly two decades ago. Why hasn’t agricultural productivity improved in Georgia over the past two decades, while it has at least recovered in every other former Soviet republic? It is even more puzzling to consider why agricultural productivity has grown by nearly 200 percent in Armenia since 1992, while it has declined in Georgia since then.

Adam’s post drew quite a few reactions from the agricultural business and economics community. These fell into three categories.

Type A reactions focused on the reasons (some well known, some less so) for the low productivity in the Georgian ag sector such as “civil war and many years of lawlessness”, “loss of the Russian market”, “land fragmentation and lack of cooperation among small farmers”, “low priority on the government agenda for so many years”, “collapse of irrigation and drainage systems”, “lack of inputs, technology, and knowledge”, “low commercialization of ag. output”.

Type B reactions (fewer in number) focused on what could have worked so well in Armenia. Possible candidates are “better utilization of Soviet era infrastructure, including irrigation”, “higher concentration of agricultural machinery”, “better ability of the country’s processing industry – such as the local brandy industry – to add value”.

Type C reactions, including one by Adam himself, were somewhat skeptical about the accuracy of the underlying data. For instance, an Armenian economist commented that “when comparing the rural life stories of our Georgian and Armenian students I did not get the feeling that the Armenian farmers’ standard of living is several times higher than that of their Georgian partners. Both groups are more similar than different to each other”.

To find the truth, we consulted two senior international statisticians working to improve the quality of agricultural statistics in Georgia and Armenia. Both tend to subscribe to the skeptical view. In particular, they suggested that the Georgian agricultural statistics are based on a rigorous survey of farmers that draws a fairly accurate picture of output and productivity concerning all the main crops. The Armenian ag statistics, on the other hand, are collected using a “reporting system based on community books that may still be influenced by the Soviet style of thinking, with a political pressure to report about increased production levels”.

Now, if Armenian statistics are truly unreliable what’s the point in using Armenia as a benchmark for Georgia (or any other country for that matter)? In despair, we turned to the (higher value) Georgian statistics.

Georgia consists of several regions all of which (except Tbilisi) have a very sizeable share of the labor force (self) employed in agriculture. The regions specialize in different types of agricultural production (crops, husbandry) due to radically different climate and soil conditions. Now, since productivity changes could not have been uniform across all subsectors, we thought that something interesting could be learned about the puzzle of agricultural productivity from a comparison of income per household across Georgia’s regions.

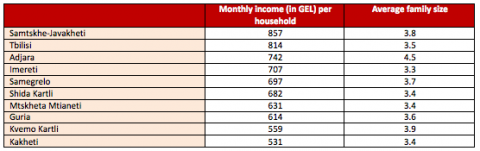

To our great surprise, instead of telling us anything about the evolution of agricultural productivity, the data are once again pointing in the Armenian direction. According to 2011 GeoStat household survey data, the region with the highest income per household (857 GEL) is Samtskhe-Javakheti. Not Tbilisi, not Samegrelo or Adjara. Samtskhe-Javakheti.

For those who don’t know, Samtskhe-Javakheti is the only region of Georgia were Armenians are in a majority (Tbilisi has the second largest Armenian population). Reflecting this demographic reality, the GeoStat sample of the Samtskhe-Javakheti region includes 198 Georgian and 477 Armenian families.

One might think that Armenian households are simply larger, but with 3.8 members per household Samtskhe-Javakheti is not far from the national average (3.6).

Samtskhe Javakheti does stand out on a quite a number of parameters reflecting or affecting agricultural productivity:

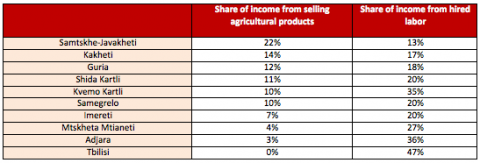

- The highest share of income (22%) from selling agricultural products (Kakheti is second with 14%). In monetary terms, an average Samtskhe-Javakhetian farmer receives 2.5 time higher income from selling agricultural products than his Kakhetian competitor. Other regions are much further behind.

- The lowest share of income (13%) from hired labor. Kakheti (17%) and Guria (18%) and are second and third on this parameter, far behind Tbilisi with 47% of income from hired labor.

- The largest area used for cultivation by an average household: 0.85 ha in Samtskhe-Javakheti compared to 0.7 in Guria (second) and 0.3ha in Adjara (last).

- No or very few large farms and a relatively equal distribution of cultivated land among households: plot sizes of interviewed households in Samtskhe-Javakheti run from 0 to 4.5ha compared to 0-48ha in Shida-Kartli, 0-17ha in Guria and 0-39ha in Kakheti.

- The highest average number of cultivated plots (including on leased land) per household: 3.4 in Samtskhe-Javakheti compared to 2.2 in Shida-Kartli and Imereti (dividing the second and third place on this parameter).

There is no escape from the Armenian productivity factor also when one compares the incomes of Armenian and Georgian households within the Samtskhe Javakheti region (who thus operate in very similar conditions). The average income of the surveyed Armenian households in Samtskhe Javakheti is 923 GEL as compared to 729 GEL for Georgian families. Armenians households own 2.5 times more land on average (1 ha compared to 0.4 ha).

The Armenian productivity factor evaporates only when we travel some 50-60 km from Samtskhe-Javakheti to Tbilisi. The GeoStat sample of Tbilisi households includes 1741 Georgian and 113 Armenian families. The average income of an Armenian household is almost twice lower than that of a Georgian one: 448 GEL compared to 867 GEL. Perhaps because agriculture is not the best money maker in Tbilisi…

Comments

My father has a farm service center and mechanization service center in Shida Kartli Region (Kaspi District). He provides agricultural services for farmers such as ploughing, cultivation, harvesting and so etc. This fall, number of his customers half diminished, even though autumn is a busy season as farmers are cultivating land for grain cultures (wheat and barley mostly). The reason for this is that farmers are waiting for new government to cultivate their land for free, which I doubt will happen. It was just like this after collapse of Soviet Union; People had expectation that new government would come and assist them to do something on their land. I believe such a low number for cultivated agricultural lang for Georgian farmers is that they don't realize that they are the ones who has to take care of their privatized land and after everyone has done little something on their land it is possible that government or other donor organizations will assist them.

Another thing I want to mention is that in my area if farmer wants to expand his farm he or she has to go through tough process to find original owner of the land who migrated somewhere else and in worse case passed away. Family members need to do paperwork to legalize land on their name and then sell it, which increases final price of the land and in most cases paperwork costs more than a land. So mostly farmers have to deal with the area they got after land privatization.

It is worth looking at houshold incomes in Marneuli also, a district with an Azeri-majority population.

Seems like Kvemo Kartli to which Marneuli belongs is quite low on income per household. Local households report a very high portion of income from hired labor (35%), sharing the second and third places with Adjara after Tbilisi (47%). This seems to suggest that the rural Armenians are more entrepreneurial than the Azeri, at least as far as agriculture is concerned.

If nothing else, this issue brings the problem of measuring or indicating productivity to the forefront. Not only is it difficult to measure or estimate agricultural productivity within a region, but cross region or international comparisons are difficult to make, even under more stable circumstances over longer periods of time in relatively developed economies. Add in the transition context, additional statistical collection, verification, and values for inputs, outputs, as well as qualitative changes in what is grown, and demographic changes, and well, I would not put too much faith in relative differences that show up, unless they are overwhelmingly large, consistent, and are under conditions where most factors are reasonably constant over a long number of years. This does not mean that productivity measures should not be made, or attempted, in these contexts, just that we should be hesitant to draw too rash a conclusion from weak diagnostics.

Your survey appers to confirm that the amount if land cultivated is not correlated to income. Am I correct?

We did not systematically check how the amount of land correlates with income but Samtskhe-Javakheti has BOTH more land and income per household (particularly the Armenian households). Land there is also more equally distributed.

I have trouble understanding why one would choose income as a proxy for productivity. One could use GDP per capita (better: GDP per worker), far more appropriate. If one would do so Samtskhe-Javakheti is the second-poorest region of Georgia, not really indicating an "Armenian productivity factor".

Income (per household or worker) should be a very good proxy for productivity in rural regions mostly populated by smallholder farmers and small family-owned businesses. At an extreme, it is exactly identical to GDP (per household or per worker), as discussed in any undergraduate macro textbook (at the national level).

It is a bad proxy of productivity in regions populated by large firms producing value that is not passed onto the local households (for whatever reason). In such regions (e.g. Tbilisi), the "Armenian productivity factor" is indeed not observable from the household data.

Which GDP data are you talking about?

Sorry, but it is a very poor proxy as income includes transfers and remittances. They later are likely to be important in Javakheti and probably explain the discrepancy. Geostat has GDP data by region, which combined with population numbers gives GDP per capita.

You are right, income from transfers and remittances could be a distorting factor. But it is not, at least not based on the same GeoStat household data. If anything, Samtskhe-Javakheti (S-J) is getting less of both, so it seems.

in 2011 S-J households reported:

1. Below-average reliance on "income from relatives" (8%, compared to 16% in Samegrelo - max, and 6% in Kvemo Kartli and Adjara - min)

2. The lowest income from "Pension, Scholarships, Aid" (10%, compared with 16% in Mtskheta-Mtianeti and Kakheti - max)

3. Slightly above-average income from in foreign currency (5%, compared to 6% in Imereti - max, and 3, 4 and 5% in all other regions except Guria which has 1%)

4. The only potentially distorting source of income on which S-J is high is "other income". Not sure how it was presented and understood. It could be income from selling an asset. On this source, S-J is second after Mtskheta-Mtianeti with 19%. Most other regions are in 10-16% range, except Samegrelo and Guria with 10% and 8%, respectively.

Ah well, now we are onto the bigger issues of productivity. While economic convention would have it that productivity is measured using output/input(s), the problem is in carrying it out. Output per worker is simply output per worker, it is not productivity. It is also not labour productivity. Output per worker, even in real terms, has to be adjusted for factors that changes other than productivity, such as product specific prices, etc. cylces, climate, accounting definition changes over time, etc. to get at whether, all else equal, the input it able to produce more output that before, and whether it is "more productive" that other inputs used in other contexts. Income per worker of per household is by standard productivity measures not a proxy for productivity. It still has to be adjusted, and derived from the inputs in the process at hand.

Surely productivity cab be measured by yield per hectare. I achieved 4 tons of wheat and 7 of corn this year. Cost and amount of inputs was much higher than the average in Georgia.

Yes, you can start by using yield per hectare, to get land productivity, and then make adjustments to the stats for the different amounts of other inputs used (quality and quantity of labour and capital, etc. among other adjustments) to see, if all else equal, some land is more productive than others. Or, you can resort to total factor productivity, which combines all inputs to produce the output, and then is similarly adjusted for those factors that need to be held (all else equal) such as quality differences, price fluctuation differences, etc. or base measures, different statistical approaches to totaling up the amount of labour used, etc.

How do you determine the employment in agriculture in Georgia? In Armenia there is always this problem of accounting as employed in agriculture persons who just possess a piece of land (larger than a defined minimum) and isn't employed in any other place.

Still it is strange that those living in S-J have reported lower than average reliance on the remittances. Armenians living there usually (and historically) are very active on the Russian labor market.

Why don't you use the statics on value added by sectors of economy and regions ? is there such statistics in Georgia available?

Vardan, agricultural employment is actually determined in the same way, here and in Armenia. This explains why unemployment is supposedly lowest in rural areas.

I am not sure that S-J remittances are lowest. They may be lowest as a share of income, but not necessarily in absolute terms. Given the large size of plots and their rather equal distribution among households, S-J population may not depend on remittances, not as much as others. [We had a blog http://www.iset.ge/blog/?p=779 on the interplay of different motivations to remit - investment vs. altruism].

The value added data by sector and region is, of course, available, and it ranks regions in a very different way. S-J ranks second from the bottom because value added is lowest in smallholder agriculture. Still the puzzle is this: Why S-J smallholder farmers are doing so much better than other Georgian farmers? Why Armenian agriculture has been (supposedly) able to exceed its pre-1991 productivity level by more than 200%, while Georgia's is yet to recover.

Yes, you need to use value added as part of the output, but the problem remains choosing what inputs were used to produce that value added (output). There is no perfect answer I am afraid and usually a mixed approach is needed - based on the specific case, data availability, conditions, etc. Some people who are part of the household, for example, are given tasks on the farm just so that they are making a contribution. But in fact, even if they were not there, the farm would produce the same amount with the remaining people - this labour actually did not produce anything, and maybe the person was given tasks simply for moral or ethical reasons - to make someone feel useful, or part of the family, or to earn their keep/maintenance! This is called "latent" labour because it is hidden in the statistics and can throw off productivity measures. It is also highly relevant in the Caucasus and Central Asia after 1990 or so when many people returned to family farms - not really adding to value added, but adding to the inputs - thereby forcing productivity to appear to decline more than it really did. This is especially true in areas where there was little private sector, urban development and partially (not fully) explains some of the possible differences in agricultural productivity observed between transition economies in Eastern Europe versus Central Asia and the Caucasus.

I think that yield per hectare may represent a true measure of input irrespective of the problem of measuring and valuing inputs as land is a finite resourse and Georgia is a net importer of almost all types of food. If Georgia increased the yield per hectare by a factor of say 4 and increased the amount of kand cultivated by 4 times I posit that would be positive for the economy. Do you agree?

David, I've just interviewed Fadi Asli related to a project we are doing on Georgia's competitiveness. Among other things we talked about agriculture. According to him, 1kg of Brazilian poultry costs about 70c in Poti, compared to $1.5 for a Georgian equivalent (ok, fresh, not frozen).

)? Say, labor, fertilizer, machinery, fuel, the cost of capital (depreciation), whatever else you used...

)? Say, labor, fertilizer, machinery, fuel, the cost of capital (depreciation), whatever else you used...

Now, 70% of the cost of poultry is the cost of feed (grain) and, according to Fadi, Brazil is vastly more competitive in grain because of its vast size and climate (three harvests a year!). Even assuming that Georgian yields per hectare go up by a factor of four (at the cost of additional inputs), Georgia is not going to be able to compete with Brazil on grains (and on poultry).

An ag statistician (quoted in the post) I talked to suggested that Georgia could do relatively well in special "niche" crops that are not as scale intensive. He was telling me how important it is to collect data and monitor productivity in these crops. At the moment, GeoStat is doing a fairly good job of covering the major crops (potato, corn, grapes), but the smaller ones need a different sampling approach.

BTW, have you been able to estimate your own (farmgate) costs of producing one unit of grain (ignoring your personal time

It is highly interesting that on average the Armenians in Tbilisi have just half the income of the Georgians. Could this be caused by an ingroup bias (discrimination) on part of the Georgians? Does anyone have an explanation why the Armenians in Tbilis are economically doing so poorly?

An interesting question, Florian. This could be the case since the best paid positions in Georgia are those in government administration (not teachers and doctors but ministers and deputy ministers, heads of departments and divisions at ministries, government agencies and investment funds. There could be ingroup bias in hiring for these well-paid positions. Not sure if any research has ever been done to explore this question in any depth. Another category of well-paid people are financial sector employees (not starting level though).