On the 8th of March, Georgia joined many other countries around the world in celebrating the International Women’s Day. While this particular way of appreciating the many contributions of the Georgian women may be said to have been inherited from the Soviet Union, women have historically played very important roles in Georgian society and politics. The most prominent among them were Medea of Colchis, St. Nino, who brought orthodox Christianity to our country, and “King” Tamar, who ruled the state in its “Golden Age“. It was during this “Golden Age“, as early as in the 12th century, that Shota Rustaveli wrote, “Lion cubs are equal, be they male or female”.

Despite these early feminist tendencies, partriarchal traditions remain deeply rooted in Georgia’s society. In particular, Georgians remain convinced that it is up to the men to provide for their families. For instance, according to 2010 Caucasus Barometer data, 83% of Georgians believe that men should be the major breadwinners in the family. That said, only 36% considered this to be really the case. Moreover, 39% believed that the main breadwinning function is actually performed by Georgian women, not men.

Regardless of local traditions and norms, gender equality has been internationally recognized as an important milestone in a country’s development. It is regarded as a basic human right, and is also one of UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for 2015. But does gender equality promote economic growth? If so, in what way?

GENDER EQUALITY AND GROWTH: WHY ARE GOOD TIMES SUPPOSED TO BE GOOD FOR WOMEN?

Gender equality, as defined by the UN, is about “equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women and men, girls and boys”. The concept encompasses many difficult-to-measure aspects of social life – customs, traditions, attitudes and believes. Here I will focus on a particular measure of gender equality commonly used in economics – female Labor Force Participation (LFP).

There is a vast economic literature analyzing the relationship between gender equality in terms of LFP and welfare. Even though there is no agreement as to what causes what (women’s LFP increases welfare, or greater welfare increases women’s LFP), there is consensus among the researchers that “good times are good for women” (Dollar & Gatti, 1999). In other words, economic prosperity and welfare go hand in hand with female LFP.

A rather simple (if not simplistic) theoretical explanation for the empirical observation that relative wages of women rise as countries industrialize was offered by Galor and Weil (1996). According to them, the process of industrialization increases the ratio of capital per worker, which raises the relative wages for females. This happens because machines can substitute for brute male force while at the same time creating job opportunities for gentle and patient female operators. In other words, the process of industrialization tends to offer greater rewards for skills in which women have a comparative advantage – such as fine motor skills in textiles (US and UK in the 19th century) or electronics (present day Asia). As the opportunity cost of not working in the modern industrial sector goes up, women increase labor force participation. As a consequence, fertility rates decline and capital per worker ratio increases even more, further stimulating economic growth and female LFP. In this way, the theory claims, female LFP and economic development reinforce each other.

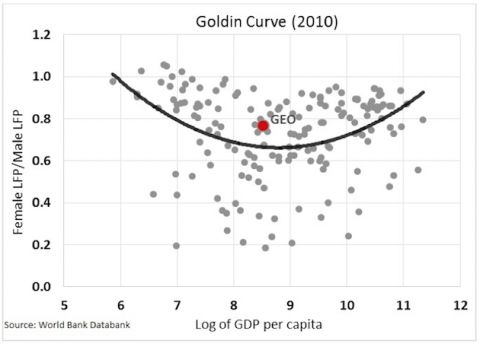

So far so good, however, the empirical relationship between LFP and economic development is not always positive. Rather, at low levels of economic development, female LFP tends to decrease as GDP per capita goes up. As observed by Goldin (1990 and 1994), female LFP starts increasing only beyond a certain threshold of GDP per capita, resulting in a puzzling U-shaped relationship.

Several explanations emerged in response. One explanation is related to fertility and infant mortality dynamics at low levels of income. High infant mortality in low-income countries creates the incentives for families to have more children than the actual “desired” number (whatever it is), as a sort of old age insurance. As income levels and welfare rise, however, the quality of healthcare services tends to improve fairly fast, leaving families with more children than they have anticipated. Thus, up to a certain threshold level of income, economic development and related declines in child mortality leave mothers with less and less time available for participating in the labor force.

Yet another, complementary explanation is that at low levels of income, economic development is mainly achieved through the expansion of traditional industries, such as agriculture, arts and crafts, which are not “rival” to child rearing. Thus, while being informally involved in the traditional sector, women remain outside the formal labor force statistics in low income countries.

ARE GOOD TIMES GOOD FOR GEORGIAN WOMEN?

With per capita income of 5,036 international $ in 2010, Georgia finds itself near the threshold income level (6,667 international $) of the Goldin curve. While not an outlier, Georgia has higher “gender equality“ than the Goldin curve predicts, implying that Georgian female LFP relative to male is higher than the average for countries with similar level of income per capita.

And the process of gender equalization and female empowerment is clearly gaining momentum! While the ratio of female to male LFP stayed roughly the same over the last decade (75%), the wage gap between Georgian men and women has been slowly but steadily closing since 2005. In 2011, the average female wage amounted to 60% of that of men. This is exactly what Galor and Weil model would have predicted. Moreover, many Georgian women are selling their child-rearing and housekeeping skills abroad by serving (often illegally) as nannies and housekeepers. As Labadze and Tukhashvili (2012) estimate, the women’s share among Georgian labor migrants increased from 40% in 2002 to 43.4% in 2008. Additionally, as Dushuashvili (2012) points out, with Russia closing its borders, Georgian women are actively migrating to Greece and Turkey. The share of remittances from these countries has consequently increased from 3% in 2007 to 14% in 2012.

If women are indeed gaining economic power in terms of relative wages, one would expect their bargaining power inside the household to increase as well. One indication of this is the dramatic increase in divorce rates experienced by Georgia in recent years, more than doubling between 2005 and 2011 (from 4 to 9 per thousand of population).

In light of this, can we say that good times are indeed good for Georgian women? I will let the reader judge…

Comments

I find the figure that the average female wage in Georgia amounts to just 60% of the average male wage quite confusing. How does this figure come about? Does it take into account different qualifications and the fact that women work more often part-time?

There seems to be an easy way to check whether or not a study controls for part-time work. If it compares "hourly wages", it takes into account part-time employment, if it compares "weekly wages", it doesn't (http://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/re/articles/?id=2160).

When Ana Revenga, leading author of the Worldbank's "Gender Equality and Development Report", presented that publication here at ISET, she came up with a similar number for Germany -- she claimed that the average woman in Germany earns less than 70% of what a man earns. As she admitted, this number did not take into account different qualifications and the fact that women are more inclined to work part-time. Presenting such a staggering figure without mentioning these crucial facts is very misleading; in my opinion it comes close to deception.

I do not know about Georiga, but in Germany I simply cannot believe that there should be massive wage discrimination based on gender. It dramatically contradicts my perception of the social climate predominant in Germany. On the other hand, it is very obvious that there are differences in preferences (sometimes denied by gender researchers). In 2009, the fraction of female students in Germany in computer science was 15.4%, in physics 18.9%, and in mechanical engineering 17.2%.

Norway is the country that arguably has the highest gender equality worldwide. Nonetheless, since 20 years the fraction of women in typical male professions is decreasing. This paradox is discussed in this installment of the controversial Norwegian Hjernevask (brainwash) series: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KQ2xrnyH2wQ.

It is outrageous and despicable if women get paid less because they are women. But it is not good for the legitimate cause of gender equality if manipulative and tendentious figures are used. It seems to me that gender research has been heavily contaminated with ideology.

Sorry, what important role did Medea of Colchis play in society and politics?

Medea from Colchis facilitated Georgia's integration in the global economy!

RT, true, Medea of Colchis is not as positive heroine from our history as others I cite here, and Greek authors did their best to make her personage even worse. However, she is the first Georgian woman, prominent and quite influential (wife of Jason and Egeos) in the world. Additionally, she is recognized as a founder of pharmacology and cosmetics. And if you ask about Georgia, according to some sources, in the end she came back to Colchi and returned the throne to her father.

From economist's point of view, I think market forces eventually allocate women's labor to its best use. And in case of inefficiencies I am sure the most part is due to traditions and it should be left to anthropologists, sociologists etc. Given the absence of all those superstitions, traditions and taboos of course, good times are good for women everywhere - return from being in a labor force becomes higher than from home production and whoever has necessary skills joins the labor force. But given the traditions and beliefs, do we know that "good for women" means joining labor force? If not, then we should ask what is good for women and if yes then we have to maybe deal with discrimination.

We do not really know that, Giorgi. That is why I left the question unanswered. As for discrimination, I also believe that it can not persist, as it is too expensive for discriminators.

Florian, I agree with your opinion. If women average monthly salary is just 60% of that of men this does not necessarily imply discrimination. Part-time jobs, qualifications, risk-aversion or alike could contribute to such a difference and that would be fair. The point I want to emphasize here is that as this wage gap is narrowing, this points to the fact that more women start working from part-time to full-time or women get better paid. I suspect both of those would be evaluated as "good" by feminists.