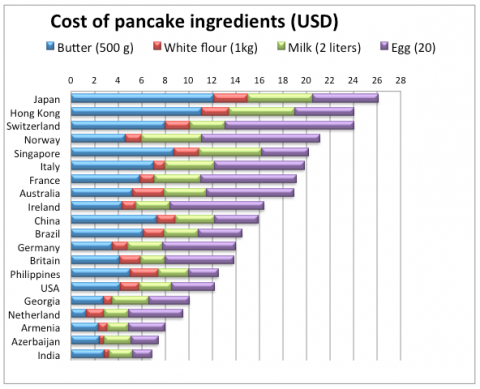

Last week, The Economist published a comparison of the costs of pancake ingredients across many countries of the world. The pancake recipe used for the calculations included flour, eggs, milk and butter – all of which are also part of the Khachapuri Index regularly compiled by the ISET Policy Institute. Thus, incorporating Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia was a piece of (pan)cake!

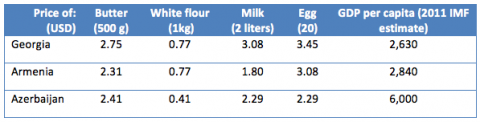

Table 1: Cost of pancake ingredients (12-15 portions) in the South Caucasus, USD

The good news is that pancakes (and khachapuri) are still a lot cheaper to cook in the South Caucasus than in the much richer Japan or Switzerland. No surprises there.

Table 2: International comparison of pancake prices

But how come pancake ingredients, and, in particular, flour and eggs, are so much cheaper in the oil rich Azerbaijan? With oil and gas export volumes at their peak, one might expect Azerbaijan to experience price inflation and a real appreciation of the national currency relative to its neighbors and the rest of the world.

Likewise, how come the most liberal economy in the region, Georgia, is more expensive than both of its neighbors? In recent years, Georgia has completely liberalized its trade, abolishing or dramatically reducing import tariffs, introducing modern customs terminals, simplifying import procedures and eliminating corruption. And yet, despite all these trade liberalization measures, the price of flour – the bulk of which is imported to both Armenia and Georgia – is not lower in Georgia than in the much less liberal and land-locked Armenia.

We will leave the question of Georgia open for discussion by the blog readers. As for Azerbaijan the answer may be relatively straightforward. First, Azerbaijan is a producer of grain. Second, Azerbaijan is a producer of oil and gas. Thus, Azerbaijan may be able to use a part of its oil windfall to directly subsidize domestic grain production (and consumption). Such a policy would disproportionately help the poor for whom food expenditures constitute a very large part of the family budget. For this policy to be effective, however, Azerbaijan would also have prevent the cheap grain and flour from leaving the country (for instance, to Georgia). This could be achieved by means of establishing a state (or quasi-state) grain monopoly. I don’t know for a fact that such an institutional arrangement exists, but this would be my (easily testable) hypothesis.

Incidentally, the policy of providing cheap bread (and pancakes, and Khachapuri) for the “populace” is probably as old as the world. For example, in Ancient Rome:

Maintenance of [grain] supply was critical to survival, especially due to the policy of distributing free grain (later bread) to all Rome's citizens which began in 58 B.C. By the time of Augustus, this dole was providing free food for some 200,000 Romans. The emperor paid the cost of this dole out of his own pocket, as well as the cost of games for entertainment … The preservation of uninterrupted grain flows was, therefore, a major task for all Roman emperors and an important base of their power.

Source: Rostovtzeff, M., The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire, 2nd ed., 2 vols. London: Oxford University Press.1957: 145.

The bread and circus tradition is still very much alive in today’s world: Egypt and other Arab dictatorships have for decades relied on food subsidies to ensure stability -- a social contract so pervasive that the Tunisian scholar Larbi Sadiki described them as "democracies of bread." Israel – purportedly the only democracy in the Middle East – used strict price controls and subsidies for basic bread until as late as 2007, when these measures were replaced by another form of “targeted” government assistance for the poor.

Interestingly enough, the cheap bread policy of the Azerbaijani government is complemented by a large investment in popular entertainment and breathtaking architectural designs (see a previous blog post by Michael Fuenfzig). In just a couple of months, this policy will bear its first significant fruit as Azerbaijan will be hosting the 2012 Eurovision contest – the ultimate modern version of the Roman circus.

Comments

Indeed a puzzling finding for an outsider. However, knowing one of the countries pretty well I guess this is a clear demonstration of how "easiness of doing business" does not readily convert itself into higher competition!

Well, I wonder who decided to use the word "Caucasus", not even "South Caucasus" or "Transcaucasia", but "Caucasus" when somebody speak about Armenia and Azerbaijan? Is this a gradual tribute to Russians to gradually wipe away the memories that Caucasus included everything including the Kuban river (including Sochi and Krasnodar region which today are presented as purely Slavic lands). I present the link to Britannica (as Brits unlike French never favored Armenians so it is hard to claim of a British favor to Armenians)

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/35301/Armenian-Highland

As for Armenia it was always part of Asia Minor having separate name of Armenia which in turn was a part of Greater Iran or Iranian Plateau. Note that Transcaucasia means "beyond Caucasus", and this term does not men anything as if you look from the Georgia to the North, it is also "beyond the Caucasus" so the Siberia is "Transcaucasia" too. My question is who decided to use the word "Caucasus" in this article, who assists Russians in their attempt to cover that Chechnya, Kabarda, Cherkessia,Krasnodar, Dagestan and other regions are the real Caucasus and thus hide away the fact of the unlawful occupation (which included massacres and eventually Genocide of Cherkess people which is officially recognized in Georgia) of the real Caucasus?!

Not even Southern Caucasus, but Caucasus!

Second, who said that Georgia is much more liberal? I mean what are the criteria for this? Reforms? Take a little time and see that those reforms were done in Armenia much earlier then in Georgia, corruption? Go to the "Voksliz Moydan" and around 5 PM take a minibus which usually carries Yezdi fruit-trader women to Armenia and see the entire beauty of Georgian border corruption. Go to the Armenian flee market and buy military and policy uniform which bears appropriate stamps that they were counted in the stock of Georgian Army or police (by the way, i wear now Georgian Army boots, much better then Armenian ones, they are made in Turkey and sold to Georgian Army).

Thanks for noting - I changed the title to South Caucasus. As for Georgia being more liberal than Armenia, in the context of the article what would matter is how easy it is to import goods into Armenia taking into account tariff and non tariff barriers, such as licensing, border "thickness", availability of storage facilities and distribution channels, etc. I was actually looking for some objective measures and data but could not find any. Your suggestions would be most welcome. The fact that the price of flour is identical across the two countries suggests that the flour market in Georgia is not perfectly competitive.

"The fact that the price of flour is identical across the two countries suggests that the flour market in Georgia is not perfectly competitive"

How?

Eric, it seems you have controlled all possible differences between individuals in different countries

By the way, if you used milk as a basis of your argument, you would have been able to tell "interesting" story for Armenia as well.

As for Azerbaijan, it imports a large amount of grain and the problem of lower prices might be the following: "Turan researched the situation in the recent years and suggested that under the guise of food grain the country mainly imports cheaper feed grain of Classes 4 and 5, which results in poor quality of bakery products and the growth of gastrointestinal diseases"

Different countries, different preferences, different opportunity costs, they matter for different prices in the countries.

Supply and Demand!

As far as I know Georgia levies import tariffs on certain agricultural products - to protect Georgian agriculture. While I don't whether it includes flour, I am pretty sure that this in iself will do nothing to promote agriculture...

Lasha, homogeneous goods that can be traded internationally should be sold at the same price in every country regardless of different tastes. The quantities would adjust to account for preferences and income levels. A much higher % of Americans use iPhones 4s models than Georgians, but the price would be about the same + VAT + small fee charged by US2Georgia for transportation.

I am not an expert, but I would think that flour or grain come close to the definition of a traded homogeneous good. Georgia has a sea port and a very "thin" border. Armenia is landlocked and flour has to travel further, by Georgian road or rail, plus it has another border to cross. Thus, Armenia should face higher transportation costs compared to Georgia. The fact that the Armenian consumer prices for flour are not higher suggests (to me) that Armenia has a more competitive distribution and retail network.

What about subsidies to the agriculture sector? It is striking that Netherlands is cheaper than Georgia. Is Geo a combination of relatively liberal trade regime with relatively constrained agriculture production (dsitribution, storage, logistics, etc)? Observe that milk and eggs are most likely domestically produced, while flour is imported.

Eteri, welcome to the ISET bloggers community!

Yes, there is something odd going on. The Dutch agriculture is probably subsidized but extremely efficient (judging by yields). Georgia's ag sector is not subsidized at all but very inefficient. Georgia's import or investment regime is extremely liberal but new entry into the inefficient sectors takes time because the market is very small. For instance, I am told that there is only one major importer of flour (not sure why, maybe because he controls the distribution channels?). I would also think that there is very little competition in the local processing of dairy products. There are just two or three plants. Prices are high and the quality is awful (I would not buy anything locally produced, but I can afford paying an even higher price). The Russian Wimm Bill Dunn (now owned by Pepsi) has built an excellent dairy plant about two years ago, but its market share is still very small.

Another anomaly is that Georgian butter is very cheap relative to milk (much cheaper than in Armenia). I cannot confirm with data, but am told that some of the locally produced "butter" contains very little animal fat (i.e. real milk). Thus, it is not really butter.

I can confirm: Dutch agriculture is heavily subsidized. Especially with regard to Milk - I have never seen milk so cheap!

Eric, You are right if we believe that static, perfect information competitive economies exist and they are in equilibrium and P=MC=MR. But... There is an array of prices for butter, milk and white flour in the supermarket below my flat

Lasha, there is a similar array of dairy products in the Populi next to my house on Gogebashvili :-). It does not mean, however, that there is a lot of choice for consumers. In fact, there is almost no choice. You've lived for a while in Spain, and can compare. The Georgian dairy sector is not really competitive, there are very few plants, the range and quality of their products is funny. Unfortunately, new entry does not happen as fast as we (consumers) would like. It takes time because the Georgian market is very small and modern plants require considerable investment. This has nothing to do with perfect competition, P=MC=MR or E=MC². Thank God, Wimm Bill Dunn (now Pepsi) opened a new plant two years ago. It produces decent fresh milk and sour cream and was able to gain market share (and shelf space in my Populi). Still, there is a long way to go...

I think the main reason of lower bread price in Azerbaijan in compared to Georgia and Armenia is the subsidizes for agricultural sector.These subsidizes increase productivity in this sector.However,the wheat fields decrease year by year and Azerbaijan import the significance portion of wheat from Kazakhstan.Maybe,the main reason for this low price is associated with low transportation cost. As we know, Azerbaijan has sea transportation with Kazakhstan and the cost of sea transportation is lower than other ones.Hence,It leads to the low price of bread.

Welcome to the bloggers' community, Vusal! Am very glad we finally have an Azerbaijani participant.

Yes, Azerbaijan is different in many ways, and having cheap supplies of wheat from Kazakhstan might help reduce the price of wheat. However, the retail price would not be as low without subsidies and/or price controls imposed through a state (or quasi state) grain monopoly. The cost of transportation is a relatively small component in the total consumer price. But I am not sure what is the actual institutional arrangement in place in Azerbaijan. Would be great to explore this in greater depth (a possible topic for your Master's thesis).

You probably wanted to say that wheat subsidies increase wheat production and not productivity (a measure of efficiency). Right? In the short run, if wheat is subsidized, farmers are likely to simply switch from, say, potatoes to wheat. In the longer run, wheat subsidies may also increase efficiency if farmers decide that wheat growing is a profitable business and invest in better seed, machinery, fertilizers, drying and storage facilities, etc. Growth in productivity may be sped up by state through subsidies that directly target investment (cheap credit, seed, etc.).

BTW, I am not saying that this is what the Azeri (or any) government should do. Subsidies come at a cost to the economy. There may be better uses for the oil money.

Lump-sum or targeted cash transfers are preferable. Let households decide whether to use these transfers to buy wheat, or a plasma TV.

Hi! Someone during my Myspace team shared this excellent website with us so I came to take a look. I’m definitely adoring the information. I’m social bookmarking and will be tweeting this specific to my followers! Fantastic blog along with great design.

მე ვფიქრობ რომ სოფლის მეურნეობამ უნდა იმუშავოს უფრო კარგად ყველგან საქართველოში თუ გვინდათ ხორბალის ფასი არ იყოს მაღალი აქ მომავალში.

I think that the Georgian agriculutal sector needs to work better if we desire that prices for wheat are not high in future. Opening your borders when you do not have local production is not a good policy.

Dear David, welcome to the ISET bloggers' community! I know you are growing wheat to provide fodder for your cattle and know more about the subject than all of us, theoretical economists, combined. But let me ask you this: Georgia has some local wheat production, which suggests that at the going global price (quite high, and potentially increasing) it is possible to grow wheat in Georgia and make a profit. Why do we need extra protection in this particular sector? Would it allow Georgian wheat production to become more price competitive in the future?