Many countries in the world run their public pension systems under the so called pay-as-you-go (PAYG) scheme, where pensioners receive their money from those who are currently working. The transfers are made through separate obligatory contributions to the pension system or through general taxes. Unfortunately but predictably, in the last decades the shrinking and ageing populations caused severe problems for PAYG systems, both in advanced as well as in less developed countries. An inevitable consequence of people living longer and fertility rates going down are higher percentages of pension receivers. Sustaining a PAYG scheme under such circumstances may bring about intolerably high transfers flowing from the economically active generation to those who receive pensions.

It was recognized by economists very early that PAYG systems are vulnerable to demographic risks, but optimism prevailed. Sufficient growth rates of the PAYG economies and, even more important, high birth rates were considered to warrant a long-run functioning of these systems. The Nobel Prize laureate Paul Samuelson called the PAYG system a Ponzi Scheme, i.e. a redistribution system that works by transferring money from those who entered later to those who entered earlier (sometimes also called a Financial Pyramid). Strangely enough, it did not cause Samuelson to doubt the solidity of the system. While ordinary Ponzi Schemes have to come to an end in a finite world, Samuelson was truly enthusiastic about the PAYG idea. In 1963, he wrote: “Social Security is a Ponzi Scheme that works. The beauty of social insurance is that it is actuarially unsound. Everyone who reaches retirement age is given benefit privileges that far exceed anything he has paid in — exceed his payments by more than ten times (or five times counting employer payments)! How is it possible? It stems from the fact that the national product is growing at a compound interest rate and can be expected to do so for as far ahead as the eye cannot see. Always there are more youths than old folks in a growing population. More important, with real income going up at 3% per year, the taxable base on which benefits rest is always much greater than the taxes paid historically by the generation now retired. […] A growing nation is the greatest Ponzi game ever contrived.”Likewise, but with a more critical undertone, fellow Nobel Prize Winner Milton Friedman called the PAYG system the “biggest Ponzi scheme on Earth”.

Also politicians were fond of PAYG systems. A PAYG system allows them to promise to those who are working (and voting) higher pensions for their future retirement – to be paid by the coming generation (which is neither working nor voting yet). When the PAYG system was reestablished in Germany after the Second World War, old people were generously endowed with pensions, though in post-war Germany there was little left of the capital these pensioners had created when they were economically active. Yet Konrad Adenauer, the first chancellor of Germany after the war, was not worried. As he famously stated: “People will always get children!”

As it turned out, Samuelson and Adenauer were wrong. PAYG systems are Ponzi schemes, but they do not work. In many countries, the irresponsible policies of the past now impose heavy burdens on those who have to finance the pensioners, and government budgets are excessively strained through the massive subsidies transferred to the pension systems.

A little bit more on pension plans: Economists distinguish between two types of pension schemes depending on whether or not they constitute an inter-generational contract. Besides the PAYG scheme, there are also funded pension schemes. In a funded pension plan, the contributions of the current workers are invested in interest bearing assets like treasury bills and corporate bonds. The capital stock built up in this way is then used to finance the future pension benefits of those who accumulated the money. While the majority of public pension systems operate under the PAYG principle and are hence unfunded, private pension schemes are typically funded.

A pension scheme (funded or unfunded) can be of the defined contribution (DC) or the defined benefit (DB) type. In the case of DB, benefits are predetermined based on the employee’s earnings when working and the length of service and age. Under the DC scheme, the level of pension payments depend on the actual contributions made and, if the plan is funded, on the returns on the invested money. Usually, unfunded (PAYG) public pension schemes are DB, although some countries have public pension systems which offer flat-rate benefits to every citizen above retirement age.

The case of Georgia: Georgia’s current old-age pension system operates as PAYG, with meager pension benefits being financed directly through the government budget (no separate public pension funds exist). The system is neither DB nor DC, since a flat-rate pension is paid to every person above the minimum retirement age. Life work times and the amount of money paid into the system are not taken into account.

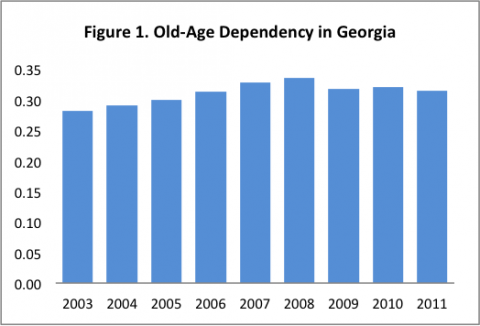

Yet also Georgia suffers from an aging population. The trend of an increasing old-age dependency ratio, i.e. the ratio of people aged 65 and above to those aged between 15 to 64, has disappeared since 2008 (see Figure 1). This releases some pressure, yet the long-run forecasts are still pessimistic. According to UN projections, by 2050 the aged population (people aged above 65) of Georgia will comprise more than 25% of the total population as opposed to 19% nowadays.

As in other countries, this demographic shift will result in a growing per capita fiscal burden in the future, bolstering concerns about the long-term fiscal viability of Georgia’s existing state-funded pension system. For coping with demographics-related fiscal risks, several options exist. The least radical policy measures try to keep the PAYG system alive by gradually changing its parameters. A typical idea of this kind is to increase the retirement age, as many EU countries already did or intend to do. Similarly, one can increase taxes and pension contributions and/or reduce pension benefits. These policies are socially and politically painful because they make one group better off at the expense of another.

The more principled approach is therefore to abandon PAYG altogether and rapidly move to a funded pension system. Unfortunately, this is practically impossible because of prohibitively high transition-related costs. The generation of workers in the transition period would have to pay for the current pensioners and build up funds for their own retirement simultaneously. To impose such a burden on the generation of current voters would swiftly end any politician’s career. The third policy option, adopted by a number of advanced and post-Soviet Union countries (for example Denmark, Netherlands, Switzerland, and the Baltic States) is known as the “multi-pillar approach” to pension reform. It has been advocated by the World Bank for many years, and essentially it aims at a gradual, piecemeal transition from PAYG to a funded system.

As suggested by its name, the multi-pillar system consists of three components (or pillars). It has a PAYG component that ensures every eligible person to receive a basic pension. In addition, it forces every working citizen to pay into a funded mandatory defined contribution plan. Finally, through direct subsidies and tax incentives it tries to encourage people to voluntarily pay into a defined contribution plan. An advantage of this approach is increased economic security due to pension income diversification.

The multi-pillar approach seems the most relevant in the Georgian context. On the one hand, in a country like Georgia with high unemployment rates and a lot of people out of the labor force, the PAYG component alleviates the poverty among elder people and reduces inter-generational inequality. At the same time, the obligatory funded defined contribution pillar ensures that the economically potent young will at least partly self-finance their future pension benefits. Arguably, this may significantly reduce the fiscal burden incurred through social benefits (which accounted for 20% of total government budget expenses in 2011) and at the same time increase private savings, which in Georgia have been dramatically low (sometimes even negative)over the past decade.

In addition, one may hope for a growth effect resulting from the introduction of the funded pension component of the multi-pillar system. This effect is two-fold. Firstly, it will increase savings that may fuel domestic private investment, fostering higher economic growth. Secondly, through the reduction of the fiscal burden more funds will be available in the government budget for pro-growth spending purposes such as public infrastructure. Public investment was an important driving force of Georgia’s impressive growth rates over the past ten years, but Georgia’s infrastructure is still far below the standards of advanced industrial countries. Although Georgia’s current demographic situation does not necessarily require an immediate restructuring of the pension system, these advantages might in themselves justify the introduction of a three pillar system.

The earlier Georgia starts the reform process the smoother will be its transition. The desperate situation in which many European countries find themselves teaches a lesson what will happen to Georgia if it lets its Ponzi scheme run too long.

Comments

Why would one even try out PAYG Scheme because, as far as I understand, Funded Pension Scheme is at least as good as PAYG Scheme in any dimension

Just the other day, I asked a few people working at ISET whether they are able to put any money aside. The answer was no. If they save at all, it is only in order to finance a nice vacation in the summer. Whatever they earn they spend on current consumption (including electronic gadgets!) and – this is important – supporting their parents and extended family. Judging by what I hear around, this is pretty much the general rule. Essentially, in addition to the government-provided meager PAYG scheme, Georgia is operating a voluntary, private PAYG system whereby every working individual is providing for the old age of his/her parents, and “unemployment” or “disability” benefits for other members of his/her household. In addition, a very significant portion of the Georgian people, up to 50% according to some counts, rely on subsistence agriculture to provide for their needs. This is exactly the way societies used to operate before the introduction of modern pension schemes in the second half of the 19th century. Thus, the Georgian people traveled some 150 year back in time.

One advantage for Georgia in establishing a mandatory funded pension pillar is related to the fact that Georgians appear to be “discounting” their future needs at rates much higher than most other people in the world. For instance, when I observe how people drink, smoke, drive and cross the Rustaveli avenue, I think that Georgians place a zero value on their future life (i.e. use a discount factor of 100%). I don’t know whether there have been any studies to confirm this psychological factor, but the very low private savings rate – even among people with reasonable earnings – seems to confirm this hypothesis. Why save for old age if you are a) unlikely to reach it, and b) don't really care. If true, people have to be forced to save for their old age. And a mandatory funded pension pillar would do just that.

Some of my Georgians colleagues are at least aware of their inability to put money aside, and force themselves to save by drawing a mortgage and buying an expensive property. At the going lending rates, this seems to be a very expensive way of providing for one’s old age.

I understand the theoretical appeal of a multi-pillar scheme and I believe it could make sense. However I do not agree that this should be interpreted as a way to "allow" the government to cut public pensions or to save money. First of all, these pensioners (those who have worked) have already paid taxes and social contributions (which are now merged together). There is absolutely no comparison between pensions in western Europe and pensions in Georgia and I doubt that most pensioners are receiving more than they paid for (directly or indirectly) to the state, during their lifetime. Secondly, it would make no sense for the public pillar to go below the 80 lari per month, an amount which is already well below the poverty line set by the government. If a state cares about its (older) citizens, that is.

Good points, Norberto. Of course there is nothing wrong with PAYG scheme if demographics are fine, in that case it might be even superior to its alternatives, and from social point of view (income distribution, equality, etc) it might be the best one can ever think of. But what we argue here is that current demographic trends are not optimistic, which may further increase fiscal burden in the future and put quite severe pressures on the fiscal feasibility of the existing plan (you will need to increase taxes or significantly cut public investments to sustain the system). So, it might be advisable to start thinking about this concern right away, in "good times”, rather than just before the time when the pension reform becomes inevitable. And it turns out that multipillar system has additional advantages (for example pro-growth effects we talk about in the blog) beyond its ability to better respond to demographic risks. As for the amount of pension, indeed, the majority of pensioners in Georgia don’t get what they contribute to the state budget in their lifetime, and that’s the point: by introducing multipillar system (which has both mandatory and voluntary DC components) this problem can be addressed; at the same time while PAYG component will be preserved, overall funds needed for its proper functioning may actually be reduced. For instance, PAYG pillar can have a means-tested form, that is people who accumulate enough funds for their retirement through the other two pillars may not be even eligible for PAYG component. In this way, PAYG benefits per-beneficiary may even increase, whereas overall budget expenses on that component may actually reduce.

I agree with most of the points. However I would like to point out that the current system Georgia has is not a "standard" PAYG system and for this reason it is not likely to face the same risks (as long as the country grows and generates employment opportunities). First of all the amount of money received by pensioners is not related the salaries received during the working life (as it was the case in other countries, e.g. Italy). As, currently, social contribution are included in the tax rate, and the amount of the pension does not depend from how much they have contributed, those with high salaries are already paying much more than they are likely to receive. Therefore, as long as the state invests this money wisely, there will be no problem of sustainability. Secondly, things will only get better (and not worse) for the public budget, as salaries and employment opportunities increase (if they do), provided that public pensions are not increased at a faster rate than salaries. This is not to deny the potential benefits of improving the pension system but to put things into perspective. It remains true that it would probably be better, indeed, to separate social assistance for the poor/weak from real pensions (linked to contributions). In this sense, one could have simultaneously 1) social assistance (for the poor without right to pension or with insufficient pensions, financed through taxation); 2) public pensions (contributive system); 3) private pension (mandatory); 3) private pension (voluntary).