Few elections in recent years were watched as carefully around the world as the Georgian parliamentary elections. And few political and economic observers shunned the opportunity to interpret its stunning outcome. The majority view, so it seems, is that Georgia passed a “litmus test for democratic governance” (Ariel Cohen of the Heritage Foundation). A few others, however, consider the victory of Bidzina Ivanishvili’s coalition as the end of the “Georgian experiment” which, according to them, was about combining radical economic reforms and universal suffrage (Yulia Latynina of Russia’s main opposition newspaper Novaya Gazeta).

The interest in Georgia and the “Georgian experiment” is not incidental. For the last 8-9 years, Georgia has been embracing a strategy of economic reforms that set it apart from all other splinters of the Soviet empire as well as most developing countries around the world. Georgia tried to grow from a very low starting point by ruthlessly eradicating cronyism and corruption while simultaneously building a democracy and liberalizing its economy. And, surprise, surprise, this strategy seemed to work.

Georgia’s success was carefully watched and scrutinized because during the past several decades, development and fast economic growth have become firmly associated with “authoritarianism”, “protectionism” and “currency manipulation”. The Chinese model, for short. At least prima facie, Georgia provided an alternative: growth through enhanced political and economic freedoms.

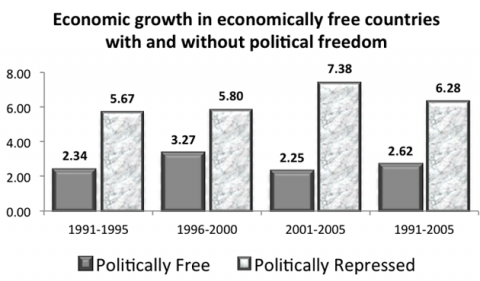

To fully appreciate Georgia’s uniqueness it is worth considering this: between 1991-2005 (the first year of Saakashvili’s administration) economically free countries that repressed political freedoms (e.g. China, Malaysia, Singapore, and Russia) grew almost three times faster than countries that embraced both economic liberalism and democracy (most developed countries). While the numbers below are not mathematically precise (they are based on rather subjective ratings of economic and political freedom compiled by Freedom House and Canada’s Fraser Institute), the general trend is undeniable. Economically free dictatorships have grown faster!

Opponents of democracy have used these and similar data to argue that new, poorly institutionalized democracies easily succumb to populist demands for immediate consumption, engage in excessive redistribution at the expense of profitable investments, and fall prey to the interests of rent-seekers. Democratic governance was also said to be prone to social and ethnic conflict, procrastination and inability to mobilize resources and get things done.

THE ROLE OF DEMOCRATIC CHECKS AND BALANCES

While Georgia’s success at fast economic growth (averaging more than 6% during the past 10 years) and modernization is undeniable, Georgia was able to avoid the pitfalls of a new, poorly institutionalized democracy because … it was not a democracy in at least one key aspect. It completely lacked a system of checks and balances that limits the power of the executive branch of government and forces compromise as the main way of political and economic decision-making. Georgia is certainly a success story as far as economic reforms are concerned, but not a 21st century miracle. At least, not yet.

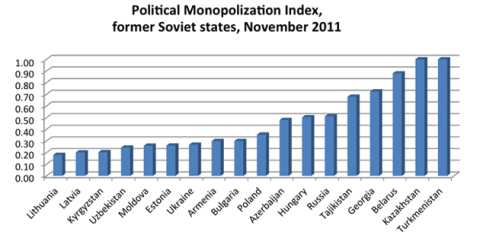

About a year ago we analyzed the extent to which democracy has taken root in the former USSR space (see 20 Years of Transition from Nowhere to No Place blog post). To assess democratic transition in the ex-Soviet states, we calculated an index analogous to the one used by economists to study market competition. Instead of market shares, our Political Monopolization Index (PMI) uses the shares of seats held by political parties in the national parliaments. It takes the value of 1 for single-party “democracies” and a relatively low value for parliaments populated by many parties of roughly equal size. To provide a benchmark, we added a few randomly selected Eastern European countries.

A note of caution: our index does not cover all aspects of democratic transition. In particular, it flatters to such “democracies” as Uzbekistan and Russia, where a semblance of political competition is carefully maintained by the ruling elites through the creation of “pet party projects“ (e.g. the short-lived Pravoe Delo in Russia). Likewise, the index ignores the quality of Georgia’s formal democratic institutions, and the ability of its civil society to mobilize itself and generate democratic change. Yet, Georgia’s 2011 position on this ranking, between Tajikistan and Belarus, speaks volumes about its perhaps overzealous young rulers’ unrestricted ability to build, implement reforms, and get things done.

If you wish, call it a dream, but what we are likely to see in the next few years is not the end but rather the beginning of the Georgian experiment. An experiment in combining a growth-oriented strategy with a truly democratic governance system – wrought with procrastination, public discussion and debate.

Success is certainly not guaranteed, but the experiment is probably worth trying. Georgia deserves a system of governance that provides citizens with a sense of dignity, not often experienced in our part of the world.

Comments

Eric, I wonder about the sample of countries and the timeframe Hassett is using. These types of analyses are particularly sensitive to both. Does he attempt to control for resource rich/poor countries?

Looking at simple correlations between democracy and growth over the span of several decades is probably misleading. After all, we forget that democracies also include highly developed industrialized countries, which of course grow less rapidly than countries like Singapore or China.

As far as the argument that democracies are bad for growth because they just can't get things done - one can argue that on the contrary, autocracies are the ones that are bad for growth because they would tend to misallocate resources (e.g. building the statues of the dear leaders all over the country - a GDP increasing activity, to be sure, but hardly growth enhancing)...

All in all, if the studies on the subject of democracy and growth manage to convince us of anything, it is that democracy on its own is hardly the magic growth pill. There must be other reasons why people value freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of assembly. May not make us rich overnight, but, as you said, does give a sense of dignity. Not by bread alone, as it were.

Thanks for your comment, Yasya! Hasset's analysis is certainly vulnerable to criticism. The sample of countries, their grouping into categories (free and not free), time-frame, the choice of GDP growth as the crucial parameter, lack of controls (level of GDP, resources, etc. etc.).

My main point, however, is that Georgia was able to achieve whatever it achieved because its rulers used a narrow window of political opportunity to clean the slate (fire all regulators and police) and implement painful reforms. During this clean up phase the government was supported by the vast majority of the population. During the second phase, and in particular after 2007, such support was no longer available, yet Saakashvili was able to run the country by "ukase" -- without any checks and balances -- thanks to having a constitutional majority in the parliament, control of the media, and strong influence on the business community. As a result, things did get done without delay, by the September 30 deadline

Democracy and Economic Growth: A meta-analysis http://www.international.ucla.edu/cms/files/Doucouliagos.pdf takes stock of a rather comprehensive list of papers (up to 2005) that analyze the question of democracy and growth in a rigorous, econometric manner.

Here is how it summarizes the literature (really funny, if you think of it):

"the distribution of results that we have compiled from 470 regression estimates from 81 democracy-growth studies shows that 16% of the estimates are negative and statistically significant, 20% of the estimates are negative and statistically insignificant, 38% of the estimates are positive and statistically insignificant, and 26% of the estimates are positive and statistically significant. This implies that three-quarters of the regressions have not been able to find the “desired” positive and significant sign."

Their literature review is quite informative as well. Here is an excerpt that I enjoyed reading:

"Does political democracy cause economic growth? Hobbes (1651) is known to have first promoted the conflict view. To Hobbes, absolutist regimes were more likely to improve public welfare simply because they could not promote their own interests otherwise. Huntington (1968) also subscribes to this view. Huntington argues that democracies have weak and fragile political institutions and lend themselves to popular demands at the expense of profitable investments. Democratic governments are vulnerable to demands for redistribution to lower-income groups, and are surrounded by rent-seekers for “directly unproductive profit-seeking activities” (Krueger 1974, Bhagwati 1982). Non-democratic regimes can implement coercively the hard economic policies necessary for growth, and suppress the growth-retarding demands of low-income earners and labor in general, as well as social instabilities due to ethnic, religious, and class struggles. Democracies cannot suppress such conflicts. For economic progress, markets should come first and authoritarian regimes can easily facilitate such policies. In addition, some level of development is a pre-requisite for democracy to function properly (Lipset’s 1959 hypothesis). All in all, this view implies that political democracy is a luxury good that cannot be afforded by developing countries. Other proponents of the conflict view and stricter state command on the economy include Galenson (1959), Andreski (1968), Huntington and Dominguez (1975), Rao (1984-5), and Haggard (1990).

Such a view became fashionable after the growth success stories in South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore in the 1950s and 1960s. The arguments rest on several assumptions, the main one of which is that if given power, authoritarian regimes would behave in a growth-friendly manner. In that vein, several contrasting cases are provided where dictators pursued their own welfare and failed ostensibly in Africa and the socialist world (de Haan and Siermann 1995, Alesina et al. 1996).

Proponents of democracy, on the other hand, argue that rulers are potential looters (Harrington 1656) and democratic institutions can act to constrain them (North 1990). Most of the assumptions of the conflict view can be refuted with good reasons (see Sirowy and Inkeles 1990, and the references therein). Implementation of the rule of law, contract enforcement and protection property rights do not necessarily imply an authoritarian regime. The latter has a tendency to confiscate assets if it can expect a brief tenure (Olson 1993) or even in the long-run (Bhagwati 1995), for more corrupt and extravagant use of resources, internally inconsistent policies, and short-lived and volatile economic progress (Nelson 1987). The motivation of citizens for work and invest, the effective allocation of resources in the marketplace, and profit maximizing private activity can be maintained with higher political rights and civil liberties. In addition, Bhagwati (1995) argues that democracies rarely engage in military conflict with each other, and this promotes world peace and economic growth. They are also more likely to provide less volatile economic performance. Finally, de Haan and Sierrmann (1995) note that a strong state and an authoritarian state are not the same thing.

Among these conflicting views and insignificant empirical results, it is natural that a so-called skeptical view has arisen. The proponents of this view argue that it is the institutional structure and organizations, rather than regimes per se, that matters for growth. Pro-growth governmental policies can be instituted in either regime. A sound leadership that will resolve collective action problems and be responsive to rapidly changing technical and market conditions is more essential for growth (Bardhan 1993). Although a supporter of democracy, Bhagwati (1995) argues that markets can deliver growth under both democratic and authoritarian regimes. However, there have also been examples that the institutional structures under both regimes are afflicted by not making the “right” choices for their subjects."

And there is more...

Well, we all know that benevolent central planner is better than market-based system )

)

Eric, I also think that the objective measure of PMI may not reflect the true situation in some Post-Soviet countries. In some of the countries a real political concentration at the parliaments can be even worse since they were able to create their "oppositions" and "neutrals" which should actually be considered as part of their own. So quality of institutions must be gauged somehow. In this regard, to have the same index calculated by subjective perception instead would lead to more precise picture. This is just a suggestion. Thanks

I very much agree with your observation, Afandi. There are other well-known efforts to estimate the strength and depth of democracy, such as The Economist's Democracy Index. I limited my analysis to a very narrow aspect of democracy: the ability of parliaments to perform the checks and balances role. And, as you rightly say, even in this regard I cannot do a good job because of, e.g. President Kerimov's (very smart) policy of creating artificial parties that provide a semblance of political pluralism. Its smells bad, but doesn't look like shit.

My plan for next week (if I manage to collect the relevant data) is to create an index of political pluralism. I will apply the same technique to the share of votes cast for each party, regardless of whether it made it into the parliament or not. I wonder what the results would look like.

Great paintings! That is the kind of information that are meant to be shared across the web. Disgrace on the search engines for now not positioning this put up upper! Come on over and seek advice from my web site . Thank you =)