Those among our readers who happened to spend a good deal of their lifetimes in the Soviet Union may remember that there was not just one kind of socialism, but there were many different versions. For example, socialist countries favored different ways to achieve industrialization and economic progress. In China, Mao pushed for what one could call “grassroots industrialization” – villages, small towns, and urban collectives were supposed to independently set up industrial endeavors. Rice farmers started to build up manufacturing plants, factories, and even steel furnaces and heavy industries. Stalin, on the other hand, fostered massive industrialization through mega projects, fueled by forced labor and guided by the iron hand of the central planners in Moscow. Tito in Yugoslavia emulated a market by introducing a system of artificial prices and letting the factories (managed by their own employees) decide how to adjust to these prices. The Sandinistas in Nicaragua and Castro in Cuba tried to achieve development through large-scale investment into the human capital of their populations, leading to alphabetization rates that surpassed many advanced Western countries. Allende in Chile envisioned what one might call an “algorithmic socialism” (sometimes it is called scientific socialism, but that is a misleading term), aiming to optimize central planning through the use of the most advanced computer technology of his days. Unfortunately, we cannot evaluate the outcome of the Chilean socialist experiment, as the CIA swiftly toppled Allende’s government and murdered him and many of his followers.

What many people are less aware of, however, is the variety of different capitalisms existing in the world. There are unique capitalistic traditions, like the Scandinavian Model, which has many elements of a socialist system. If you want to rent an apartment in Stockholm from private landlords, you have to sign up on a list and wait in a queue for several years. When you have waited long enough, you can rent an apartment at a rental price determined by the government. That is not far away from how it was to buy a car in socialist countries like Eastern Germany. Having money was not enough – one had to sign up on a waiting list and wait up to 12(!) years before a “Trabant” was delivered.

Then there is the Rhine Capitalism which assigns a less central role to the state – the government provides a framework in which competition takes place. It guards this competition through strong antitrust authorities, but it does not organize economic processes directly. Conflicts between different groups are solved through compromises, sometimes facilitated through government pressure.

At the other end of the spectrum, there is the Angloamerican Capitalism, emphasizing the freedom of individuals to engage in economic activities without being disturbed by the state. The role of the government is minimal; intervention occurs only in exceptional cases, and even then rather reluctantly.

The difference between the European and the Angloamerican philosophy of capitalism can be illustrated by looking at health care in Europe and the USA. Prior to the Obama reforms, the provision of health care to the American population was almost exclusively left to the market, leading to big parts of the population lacking health insurance coverage. In Europe, on the other hand, health care is primarily organized through the state, either through heavily regulated markets, like in Germany, or through a fully state-run health sector, like in Italy and the UK. The UK is an exception in this respect, as by and large it leans towards the American model, but its health sector is run as in a socialist country. Almost all doctors in the UK are employed by the state.

The spectrum of different capitalisms can also be illustrated by looking at the share of the government in the economic activities. For example, in the year 2012 a share of 56.2% of the gross domestic product of France was generated through government activities. If one thinks of capitalism vs. socialism to be poles on a continuous scale, one would have to consider France to be more a socialist than a capitalist society. In the USA, on the other hand, the government share is traditionally around 35%, though it went up after the 2008 financial crisis and amounts now to more than 40%.

SHOULD GEORGIA INTRODUCE MINIMUM WAGES?

The United National Movement followed an economic agenda that leaned towards the Angloamerican version of capitalism. Government regulations were minimal, taxes were flat, and one tried not to interfere with the market forces. Since the elections, however, the general orientation of economic policy has changed. Georgia will be introducing a couple of measures that have a clearly European flavor. There will be the labor code reforms, among other things forcing employers to provide reasons for layoffs that can be contested at the courts. Similarly, a competition law is about to be implemented, allowing the Georgian authorities to break up monopolies and cartels.

As there was no “objectively best” socialism in the past, there is no “objectively best” capitalism today. Whether one prefers the European or the Angloamerican model crucially depends on one’s beliefs about the performance of free markets. Are markets generally capable of solving economic and social problems, or do they typically fail? Also ethical questions are touched on. Is the inequality that comes about through the free play of market forces a great concern, or is it a low price to pay for economic development? Should the government restrict the freedom of its citizens to pursue their economic goals, or should it respect individual freedoms above everything else?

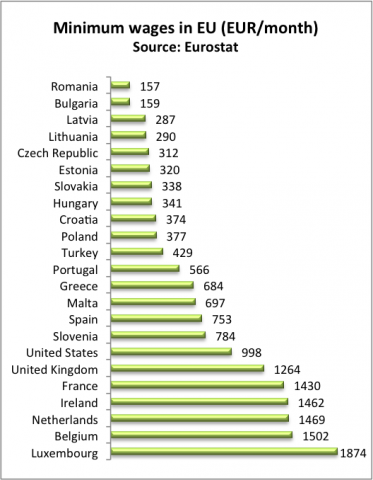

It is interesting to discuss the orientation of economic policy with regard to a concrete policy measure. Minimum wages were not picked up yet in the Georgian debate, but they are a typical issue that separates liberal economists from those who have socialist inclinations. As can be seen on the Chart, many countries in the world have introduced a law that forces employers to pay a minimum wage, and the levels of these minimum wages vary considerably. While in Romania, an employer is not allowed to pay a monthly salary below 157 Euro, in Luxemburg it is illegal to work for less than 1874 Euro per month.

An interesting thing to note is that minimum wages do not divide Angloamerican countries from those that have a more European tradition. In fact, USA and UK have rather high minimum wages, while the Scandinavian countries Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, as well as Austria and Germany, do not have minimum wages at all. This apparent paradox can easily be explained. In Scandinavia, Germany, and Austria, the welfare state endows every citizen who does not work with relatively generous transfer payments, sufficient to cover more than the basic needs. Therefore nobody is really forced to work – if the wage that can be realized on the labor market is not satisfactory, individuals can decide to stay out of the labor force and sustain their livings through transfer payments. In effect, nobody will work for wages which are below the transfer payments, and hence they essentially play the role of minimum wages elsewhere.

It would not be surprising if also the Georgian government would put minimum wages onto their agenda within the near future. But would that be a good idea?

The classical argument against the introduction of a minimum wage is the adverse effect it will have on labor demand. According to neoclassical economic theory, a company will hire new workers as long as the wage that has to be paid to them is lower than what they contribute to the company. Technically speaking, wages of workers are assumed to correspond to the marginal productivity of the workers. But this means that if there is a minimum wage, then those workers whose productivity is below this threshold will not find employment. A company that would hire them would incur losses. As a result, minimum wages would hurt those who are at the bottom end of the productivity scale. The least productive will not find jobs anymore, and unemployment in the society will increase.

Those who are in support of minimum wages point at the unequal bargaining power of companies and employees. For many segments of the labor market, the supply of labor exceeds the demand. As long as a worker does not have unique expertise that makes him a sought-after specialist, it is not a big deal for a company to replace him. In addition, workers must sell their labor, as they have to feed themselves and their families. In the absence of transfer payments, a worker can hardly opt for withholding his labor from the market if wages are too low. This competition among workers for workplaces provides the employers with opportunities to offer lower wages than the workers’ marginal productivities. In other words, the workers do not receive their “fair share” of what they produce, but are forced to accept almost any wage offered to them. If one adopts this standpoint, minimum wages are a reasonable means to compensate for the weak bargaining position of workers vis-à-vis the employers.

Of course, if one would introduce minimum wages in Georgia, they would have to be adjusted to the general economic situation of this country. The average monthly salary in the year 2011 in Georgia was 636 GEL, and wages varied considerably across sectors. While the average monthly nominal salary of employees was the highest for financial intermediation services (1268 GEL), in public administration employees earned only 999 GEL on average, and in the education and agricultural sectors, these numbers were 320 and 393 GEL correspondingly. As minimum wages are typically not sector specific, minimum wages should be determined according to the lowest salaries. So they should be less than 300 GEL.

In Georgia’s current situation, however, it is highly questionable whether the country can afford the introduction of minimum wages. Many Georgians are struggling to find employment at all and earning possibilities are very limited. Minimum wages would artificially worsen the situation. If Georgia continues its growth path for many years to come, the situation will look different, and minimum wages may be a policy measure to be seriously considered.

Comments

Anglo-American capitalism is often defined where "The role of the government is minimal; intervention occurs only in exceptional cases, and even then rather reluctantly." However, anyone who has run a company in those jurisdictions would dispute this vigourously. Arguably the Anglo-American model only exists in the imagination now.

The UK has surrendered much of its sovereignty to Brussels and its business operators labour under a dense web of EU, national and local council regulation which discourage investment and employment. The cost of compliance with the top 100 EU regulations on business in the UK is estimated to cost a staggering net 3.5% of GDP, by the calculations of the EU's own European Commissioner for Industry and Enterprise. I doubt anyone who has run a company in the UK would claim that UK bureaucrats intervene " only in exceptional cases, and even then rather reluctantly"; Health and Safety, and Environmental Protection are both areas in which intervention is aggressive, constant and expensive to deal with even if everything is in order.

The USA likewise abandoned small government some time ago, with Washington expanding its powers incrementally year by year, and state regulations and tax burdens in some states exceeding that of many European countries. There was little reluctance demonstrated by the US Federal Government at nationalising struggling carmakers, picking winners like Solyndra, or implementing Obamacare; these were cherished policies of the political establishment that draw the State into the heart of economic activity as a participant rather than a regulator.

While the "Anglo-American model" of individual liberty and limited government may have been alive and well in the UK and the American colonies at the time of Adam Smith, it now exists only in memory. Even Georgia in Misha's first term of government, despite its laissez-faire image, had substantial behind-the-scenes State involvement in big business activity. In UNM's second term firms owned or invested in by the State began quite aggressive competition with the private sector, and government started the programme of subsidy vouchers to smallholders in the countryside which has now been expanded.

The last extant example of the Anglo-American model arguably was Hong Kong pre-1997.

Simon, in order to conceptualize we need to operate with "ideal" models, "ideal" types, and just philosophical ideas that may be far apart from their empirical manifestations in the reality of the 21st century

the Swedish society, but I would think that it is more homogeneous and solidarity-based than the British one.

the Swedish society, but I would think that it is more homogeneous and solidarity-based than the British one.

The British society, as I experienced it in my early 20s, is bound by so many conventions, let alone government regulations, that one is left with very little freedom of choice. Life is pre-programmed: whom you will become depends on where you are born and to which parents; you are supposed to go to a particular kind of school and college; even your drinking hours are strictly regulated (thank God you can drink as much as you want). Very importantly, you are forced to drive on the wrong side of the road!

On a more serious note, what struck me in the UK is the strong class divide, amplified by accent/dialect peculiarities (which remain a mystery for me). Perhaps, the fact that the lower classes tend to acquiesce to their jobs and social status implies that there may be less political pressure for redistribution.

I may be idealizing

Eric, what you say exactly coincides with my observations. I was never living in England, so I do not have first-hand information. However, I have the perception that the English seem to be quite relaxed about their lower classes. In their point of view, every society must have an upper class, a middle class, and a lower class. If there is no lower class, the society is incomplete. Therefore there are less efforts being made in England to homogenize society by empowering and educating the lower classes. I may imagine that also the huge problems England faces due to immigration are exacerbated by a lack of concern for lower classes.

Dear Simon, These are interesting points you raise. I totally agree with your frustration about the EU. There is not much good coming from Brussels these days. Prohibiting light bulbs is one striking example of this vicious tendency of European bureaucrats to intervene into national matters in a harmful way. I can imagine that this causes some trouble to the UK economy, and perhaps it costs some growth, but I see the main problems of the UK elsewhere. Well, that is another issue...

In general, your standpoint seems to be pretty libertarian. Whether one thinks that the UK (and the USA) is not market economy enough is a matter of the ideals one subscribes to. If it would work out, I would love to have a world as was favored by Ayn Rand. Yet I think that the problems inherent in pure market society are underestimated by the libertarians. Health care is a good example where decentralized markets just don't work well (by Utilitarian standards), and I therefore consider Obamacare to be a necessary step in the evolution of every market economy. That it came so late in the USA, after almost 250 years, may be due to the enormous success the USA had for all this time without general health care. But sooner or later you cannot avoid it, even if you are the USA.