According to the Biblical Book of Genesis, Adam ate the forbidden apple, and now we all have to face the consequences: men have to work “by the sweat of their face” and women have “in pain to bring forth children”. Ever since this fateful event, known as the “Original Sin”, the human condition has become a mess, of which(perhaps) the state of the world economy provides a vivid illustration.

When economists talk about the “original sin”, they have in mind a situation where a country or company is forced to borrow in a foreign currency. Thus, as they accumulate debt, their balance sheets reflect a so-called “aggregate currency mismatch” – while their liabilities are denominated in, say, dollars, their assets are denominated in a local currency. This situation is very common for developing countries and firms in those countries.

Is this a problem? YES, if accompanied by large fluctuations of the exchange rate. Back in November 2008, Georgia faced the need to implement a one-shot 20% depreciation of GEL (caused by the double shock of war and global financial crisis). The result was a rapid increase in the share of non-performing loans issued by Georgian banks to local firms. While the loans were denominated in USD, the borrowers’ revenues -- the “original sinners” in this example – were more often than not denominated in GEL. And in November 2008, these GEL revenues were suddenly worth 20% less.

FIGURE 1. GEL/USD exchange rate has been very stable since April 2011 as a result of NBG policy. Note the one-shot 20% devaluation of the GEL in November 2008 (circled in red).

The extent of aggregate currency mismatch on Georgia’s balance sheet is closely related to the process of its integration into the global financial system. Several years ago, most Georgian banks were owned by individual local investors. Now, foreign banks and holdings are majority owners in large domestic banks, while other institutional investors are represented in the ownership of various Georgian banks.Such a trend in ownership structure reflects increasing trust in the Georgian economy on the part of foreign investors and an opportunity to integrate into the global financial markets.

Indeed, the Georgian banks are now able to borrow from foreign wholesale markets and in order not to face the currency mismatch problem on their balance sheets, they also prefer to lend in foreign currency (and, consequently, receive revenues in foreign currency). The result is the persistence of high levels of loan dollarization.

[There are, of course, other factors that keep dollarization at a high level in Georgia. First, Georgian households trust the US dollar more than GEL as a store of value. Thus they prefer to save in foreign currency (65% of total deposits are in USD as of Dec. 2012). Second, durable goods (real estate, cars, etc.) are typically priced in USD and people are accustomed to using USD as the de facto unit of account!]

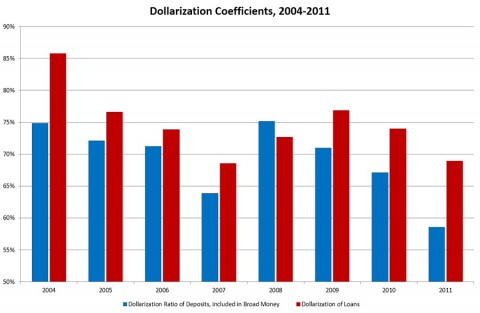

FIGURE 2: Deposit and loan dollarization peaked in 2008 and 2009 but has been declining ever since

FROM EXCHANGE RATE RISK TO CREDIT RISK

Does the attempt by the Georgian banks to avoid the currency mismatch problem make the financial market any more risk free? The answer is NO. By lending in USD, Georgian banks merely shift the currency mismatch problem onto domestic firms (the borrowers). As shown in the graph, 68% of total loans are denominated in foreign currency, while 70% of the borrowers’income is in GEL. Thus, the borrowers’ repayment capability (with the exception of exporter industries) critically depends on the stability of the exchange rate, and so does the asset quality of Georgian banks. The exchange rate risk is merely transformed into credit risk, but, as it does not disappear from the system, the banks remain vulnerable to the “original sin” problem and the currency mismatch-induced credit risk.

The GEL exchange rate has been quite stable over recent years, but there is no guarantee that it will remain stable in the future given the presence of large trade and capital account imbalances. Georgia’s monetary authorities have only a limited capacity to absorb shocks. Political events, for instance, could quickly (and permanently) affect Georgia’s fortunes as a receiver of foreign aid and capital, leading to a large depreciation in GEL. This will hurt everybody in the country: households, since the dollar value of their income will decrease and so will their ability to repay loans; domestic firms (except exporters) who import intermediate inputs and final products from abroad and sell in local currency; banks, as the value of their assets will erode with the increase in bad loans, and savers who keep their savings (in any currency) in potentially insolvent banks.

ARE THERE ANY SOLUTIONS?

First, most obviously but unrealistically, Georgia can decide not to borrow in foreign currency. An autarchic financial market will face no currency mismatch problem because it will have no external debt. This response, however, clearly has its costs. Georgia will forgo all the benefits associated with borrowing: additional investment finance and consumption smoothening.

Second, the National Bank of Georgia and the Georgian banks can try to increase GEL-denominated liabilities, i.e. deposits with local banks. This would enable banks to denominate their loans in GEL while avoiding foreign exchange-related credit risks. How can this be achieved? One way is to increase public confidence in the local currency. Importantly, greater confidence in GEL can act as a self-fulfilling prophecy. By increasing their GEL savings, Georgians will indeed make the country’s financial system less vulnerable to currency-induced credit risk.

Finally, Georgia could introduce a fixed exchange rate regime managed by a “Currency Board”, as has been done by Estonia. An even more credible version of the same policy would be to abolish the local currency and adopt the Euro or USD as the main legal tender in the country. This would simply do away with inflation, devaluation and the currency risk problems. The main risk for a country adopting such a policy is in losing the ability to use inflation and devaluation of the national currency as a means of reducing local production costs (salaries) vis-à-vis the rest of the world. An argument could be made that having such ability could make the country less vulnerable to shocks in aggregate demand.

There are, however, other ways to deal with aggregate demand shocks. Estonia avoided devaluating its currency and, indeed, had one extremely difficult year in the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008-9. Yet, within a year, it was able to cut local salaries and maintain its international competitiveness without reverting to the money press and inflation. In January 2011, Estonia adopted the Euro as the sole legal tender in the country. In the same year, its economy grew by 8%.

The seemingly outlandish proposal to introduce a currency board or abolish the GEL should be given serious consideration by the Georgian policymakers because the currency mismatch problem poses grave risks for foreign lenders and could be one of the main reasons for the high interest rates observed in Georgia. Moreover, monetary policy is in any case very ineffective in a dollarized economy, and there are significant costs to managing the money supply and maintaining the monetary policy department at the NBG.

In a way, introducing a currency board or adopting the EUR or the USD as the legal tender would get rid of the “original sin” problem by chopping the apple tree!

Comments

Currency board/full dollarization would the most stupid thing a government could do now. Taking out the war/crisis period, when people understandably decided to move (temporarily) to dollar, the dollarization coefficients have been steadily decreasing. We are not the only country to have such a problem and a number of countries have been successful in overcoming it without resorting to drastic measures.

Having own money may be considered a symbol of political independence (outside the EU). But what exactly are benefits of having the ability to print own money, managing money supply, targeting inflation, and maintaining an expensive monetary policy department? And what are the costs (including the risks associated with "the aggregate currency mismatch" problem) for the banking system and the Georgian borrowers?

At the very least, someone (and not the National Bank) should come up with the calculations.

This expensive monetary policy department, as you call it, and NBG as a whole, is the largest employer of ISET alumni And let me remind you that Israel had a similar problem and somehow did not decide to abandon shekel and move to USD.

And let me remind you that Israel had a similar problem and somehow did not decide to abandon shekel and move to USD.

By the way, the "expensive" monetary policy department, in reality is just a 5-employee division. Surely it is the most costly unit in Georgia. Maintaining currency board department would surely be more expensive. As for the costs - borrowers should borrow in GEL, particularly now that the mortgage rates have fallen below 11% in GEL.

))

))

Мораль у сказки такова - check your facts

Giorgi, all I am saying is that it would be good to check the facts and come up with an estimate of the costs and benefits of having own currency for a small country like Georgia. And the cost estimate should include an assessment of the risk premia Georgia and Georgian firms are paying to account for the currency mismatch problem, as discussed in the article.

Estimating the benefits may be somewhat easier...

I'm pretty sure there is one, done by the NBG guys. I can find it for you, if you wish...

Maya, many thanks for initiating this discussion. It is an interesting and relevant question. Here are a few points from me.

1. It is incorrect to say that adopting Euro or dollar would “simply do away with inflation.” First, you probably mean inflation differential, meaning that inflation in Georgia will become the same as in the country of the adopted currency (Euro area or the U.S.). But secondly, that is not correct.

Imagine, for example, two countries sharing the same currency but one energy-independent, while the other relying on imports of gas and oil. A change in global prices would clearly affect the second country, but not the first. Alternatively, imagine that one country is rich, while the other is poorer, but converging to the first one. That means that wages in the second country are growing faster and subsequently, overall inflation in a poorer country is higher.

You can look at the data here and see for yourself that, say, in 2004 inflation in Spain was 3.1 percent but in Finland it was 0.1. Or that in 2010, in Greece it was 4.7 while in Ireland it was -1.7

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=57&pr.y=7&sy=2000&ey=2012&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=122%2C136%2C124%2C137%2C423%2C181%2C138%2C172%2C182%2C132%2C134%2C174%2C184%2C178&s=PCPIPCH&grp=0&a=

2. It is a very popular thing to refer to the experience of the Baltic countries (with Anders Aslund being a big proponent and Paul Krugman being an opponent). But one needs to take into account that their decision was NOT driven by economics but by politics. The Baltic States are determined to become part of Europe and do away with the association with the Former USSR. Thus, they were ready to do many things (including dramatic wage cuts to deliver a so-called “internal devaluation” that substitutes for external, currency devaluation). Are you sure Georgians will be willing to do the same? I am sure they won’t.

3. Similar to transformation of the exchange risk into a credit risk, introduction of the dollar or euro does not remove the problem, it only transforms it into something else. For example, in the case of the Euro zone, introduction of the common currency let to declines in the interest rates in many weaker countries, resulting in credit booms and overspending, which a decade later led to major problems.

4. Finally, it;s a big question, how credible such things are. Argentina in 2001 decided to give up its currency board. Today speculations abound that Greece of Cyprus will leave euro. Whether it will happen or not, doubts are there.