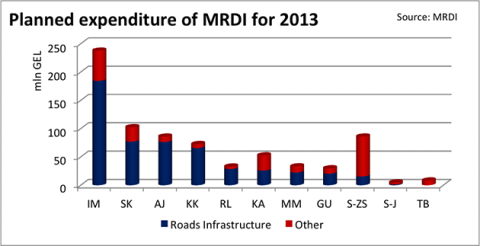

Development of municipal services and infrastructure, in particular transportation infrastructure, is one of the pillars of the State Strategy on the Regional Development of Georgia for the period 2010 to 2017. Even though the strategy was approved by the previous government, the new government is not only committed to continuing all the planned infrastructural projects but is also going to start new projects, focusing on upgrading the regional infrastructure. According to the planned budget for 2013, the Ministry of Regional Development and Infrastructure (MRDI) is expected to spend 501.7 mln GEL (55.7% of the ministry’s 2013 budget) on road infrastructure improvement. Looking at the figure below, only four (Kakheti, Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti, Samtskhe-Javakheti and Tbilisi) out of eleven regions are going to spend less than half of their development budgets on road construction and rehabilitation in 2013. This does not necessarily imply that the government places less weight on having quality roads in these areas, but simply that important large-scale projects have already been completed in these regions and the focus has been directed from roads to other priorities. Not only is the government concerned with having more and better roads on both the regional and national scale, but the ministry also believes that “Infrastructure improvement represents one of the key preconditions for regional development” (MRDI action plan 2013).

With such an emphasis on roads, it is a valid question to ask whether road infrastructure is indeed meant to serve the regional development goals or not. In fact, it depends on how we define and measure regional development – which itself is quite a blurred concept. The main objective of the State Strategy on Regional Development of Georgia is to create a favorable environment for the socio-economic development of the regions and improve the living standards and conditions of the population. The objective will be attained through a balanced socio-economic development of the regions, increased competitiveness and minimized socio-economic imbalances amongst the regions (State Strategy for Regional Development of Georgia for 2010 – 2017) — still vague, but that is how regional development is understood in Georgia.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS AND EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

In general, infrastructure is an input into aggregate production that serves as a way to increase efficiency of utilizing conventional inputs (such as labor, land, capital) through reducing the various transaction costs. Therefore, endogenous growth theories have claimed that public investment in infrastructure can raise the economic growth in the long-run. For the World Bank (WB), an international organization that largely advocates and supports investment in infrastructure, a global infrastructure initiative is a growth-lifting strategy. As for the magnitude of impact, this is usually quite difficult to measure due to the endogeneity of infrastructure provision (infrastructure provision is not always the reason, but sometimes the result of economic development). The latest WB research has estimated that a 10% improvement in infrastructure provision will lead to a 1% GDP growth in the long-run. Although beneficial for economic growth at the national level, it is not clear-cut that the effects of improved infrastructure will be the same at regional levels. Moreover, there is no guarantee that the increased availability of infrastructure, roads in particular, will help minimize socio-economic imbalances amongst the regions.

It is an established regularity in economic geography that when interregional road infrastructure improves it usually leads to a concentration rather than a diversification of economic activity. The mechanism works as follows: better roads improve market access for firms in both lagging and leading regions. Firms in leading areas are usually, almost by definition, more cost-efficient and, therefore, more competitive than those operating in lagging areas. Lowered transaction costs give them the possibility to sell their output in lagging areas, too. As a result, production gets concentrated in leading regions, exacerbating pre-existing regional disparities. This is especially true for sectors exhibiting increasing returns to scale (output increases by more than proportional change in all inputs, in other words, scale).

However, as trade is mutually beneficial, lagging regions will also benefit. Two channels are worth emphasizing. First, reducing transaction and transportation costs encourages trade between the dissimilar regions that specialize in the sectors of production that they have a comparative advantage in. In the Georgian case, road infrastructure would foster Kakheti specializing in wine production, Samtskhe-Javakheti in dairy products, Svaneti in tourism and so on. And second, price level reductions will occur in lagging areas due to more efficient production process and reduced transport costs which benefit consumer welfare at large in these regions.

These channels were empirically validated for the Chinese case by Benjamin Faber of the London School of Economics in 2012. His empirical exercise has shown that remote counties, linked to other regions through the National Trunk Highway System (NTHS), were negatively affected in terms of industrial, non-agricultural and total output growth. Nevertheless, peripheral regions benefitted from price index reductions.

CONCLUSIONS

Putting aside the negative externalities associated with road infrastructure, such as pollution or accidents, road improvement has merits in many respects. The fact that it will not necessarily facilitate balanced socio-economic development of the regions is not a reason to cancel those road infrastructure improvement projects. However, it would be good to see the state’s vision concerning why it is being done and what the final goals we are trying to achieve are. If we take regional GDP growth as an observable indicator of regional development, then there is a high chance that we will not be able to get that. However, taking into account the greater potential for labor mobility (inter-regional commuters, for instance), regional GDP would provide quite an irrelevant indication of the living standards of the population in a given region. Moreover, if people are free to migrate to other regions (and mostly, they are), even existing regional disparities become economically meaningless. Although we do care about the lagging regions, they are not the priority per se; we care about them simply because of the welfare of the population residing there.

Comments

Obviously, the general points about (potential) benefits from an improvement in existing infrastructures are valid. I doubt, however, that regional GDP will (or should) become completely irrelevant in terms of policy. It is sufficient to think to those individuals (the elderly for example) who are less likely to migrate and are more likely to "be left behind" as younger people move, following labor market opportunities. This is, obviously, only one example. I suppose in several other cases (as you suggest) it could be possible to identify both "winners" and "losers" created by this policy. This said, a crucial issue that should be discussed publicly, in my opinion, is how to make sure that (potential) gains are shared between those who reap them and the "losers".

The economic geography theory invoked in the article is mostly relevant for manufacturing activities. Indeed, better road connections will lead to a greater concentration of manufacturing in the core regions (provided there is economy of scale in production).

However, the regions we are mostly concerned with are agricultural regions. Production of grapes will not shift from Kakheti to Tbilisi even with a German quality highway connecting the two. Production of hazelnuts will not shift from Western Georgia. And Samtskhe-Javakheti is not likely to loose it dairy and potatoes. Better roads will make the products of these remote regions more readily available for processing, local marketing and exports (through the new airport in Kutaisi, Tbilisi and/or Poti/Batumi ports).

As I argued in Roads and Rural Development: the Case of Samtskhe Javakheti, the MCC investment of $209 million in the road infrastructure connecting Samtskhe Javakheti to Tbilisi, Nino Tsminda and Akhalkalaki seems to have a tremendous impact on agricultural production and household incomes in the entire region. What has not yet happened in Samtskhe Javakheti, in line with the arguments presented in this article, is investment in the manufacturing and processing capacity. These activities remain concentrated elsewhere.

NP and Eric, Thanks for your comments.

NP, yes, I agree that regional GDP is not completely irrelevant but it is not a good indicator of living standards in the regions. GDP of Guria might not be high but as many people commute from Guria to Batumi and work there, Guria's GDP will substantially underestimate the quality of life in Guria. As for elderly, they are mostly supported financially by their offsprings (at least when talking about Georgia). So, better labor market opportunities for younger at least to some extent translate to better living stadards for elderly also.

Eric, manufacturing is the sector which I had in mind when talking about sectors exibiting IRS. And Samtskhe-Javakheti is a good example of what we should expect from roads and what we should not.

Re GDP as a relevant indicator, especially at regional level, I'm reminded of an article in the London Times a couple of years ago by the Head of the London Stock Exchange in which he observed that "No one ever paid their mortgage or bought their groceries with GDP. Recovery needs to be felt by the man in the street, it needs to reach our back pockets and it needs to produce jobs."