Members of the same nation have the same “cultural background”, which means that they share a good deal of political and social values and ideals, and they tend to believe in the same recipes to solve their problems. Such fundamental attitudes are often shaped by the historical experiences of a nation. For example, England had a kind of merchant democracy since the 14th century, when the House of Commons was founded. In the former Ottoman Empire, on the other hand, merchants had no institutionalized possibility to influence politics. Bribery and utilizing on personal connections were the only options to foster business interests. Does this not influence the way how business people approach politics in England and in a province of the former Ottoman Empire like Egypt even today?

Well, not in the contemporary economist’s view. In one of the recent tries to explain economic prosperity and failure on a grand level, the famous MIT economist Daron Acemoglu and his co-author James Robinson from Harvard set up a theory which explains economic success without references to values, traditions, or character traits of people. This is in line with the standard economic approach, which describes economic processes to be exclusively determined by (material) incentives. Moreover, these incentives are assumed to work in the same way for all people in every country and in every period. There are other approaches, but they play an almost negligible role in contemporary economic thought.

Personally, I believe that modeling human behavior as a sheer reaction to material incentives is a pretty impotent way to analyze economic affairs. Compare the Tibetan’s strategy to fight for one's own country with that of the Kurds with their PKK or the Palestinians with their various militant organizations. It is obvious that the Tibetan methods to resist the occupation of their country are restricted by the fact that, as I read recently, their religious belief “hardly allow[s] them to kill an insect”. Yet as a conflict economist who subscribes to Anglo-Saxon mainstream economic paradigms, one would ignore these “soft factors”. Rather, one would reason that it is in fact an optimal strategy for the Tibetans to remain non-violent in their struggle, given the material incentives they face. Likewise, also the Kurds and the Palestinians have material incentives to act as they do.

However, if one accepts that values do matter, an interesting question arises: Are there values and cultural traits of the Georgian people which may be instrumental for facilitating their economic development? I suspect there are.

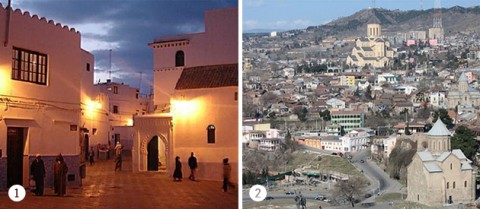

When I was 17, I traveled with a friend to Morocco. We arrived with a ferryboat from Southern Spain, and immediately were surrounded by a hoard of people who wanted to sell us various things, from taxi drives to hotel accommodation to tourist merchandise. We somehow made it to the train to Casablanca. In the train we were approached by a friendly guy who involved us in a conversation. In the end, he offered us to stay in his apartment in a town called Asilah, which was on the way to Casablanca. We really trusted this guy, as he seemed to be intelligent and eloquent. Yet in Asilah, he took us to a tourist shop, and we were urged to buy the traditional dress of the local people. We were promised that if we were dressed in a djellaba and we would wear the traditional Moroccan shoes, people would consider us “guests”, not “tourists” anymore. After buying this stuff, we went to the apartment of our acquaintance and ate couscous. Then he began to smoke marijuana and urged my friend to also take a sniff. Out of politeness, my friend agreed. In that moment, a policeman entered the room. He lectured us about the evils of smoking marijuana, and he set up a scenario of us being jailed. We knew that while it was very common among Moroccans to smoke weed, foreigners who did the same thing were frequently incarcerated in one of the infamous Moroccan jails. At the same time, it was clear that this policeman just wanted to be bribed. So we gave him some t-shirts and other belongings from our backpacks, and indeed he left us alone. The story had a dramatic ending. We were quite terrified by this experience and we decided to return to Spain immediately. Yet the next morning, when we were alone in the apartment, we saw a chance to take revenge. We thoroughly demolished the furniture, the kitchen, and whatever else could be found. Then, dressed in our traditional Moroccan outfit, we rushed to the train station, being afraid that our host would discover the destructions and come after us. We hoped that with our new clothes, we would blend into the local population, but it didn’t work. In fact, we were the only ones dressed in djellabas. The people in the street were pointing at us and laughed, and a group of children were following us. At the railway station, the train was late, and we had a tough time waiting for two hours, always watching fearfully whether our host would appear. We left Morocco on the same day and swore to never come back.

When I arrived to Georgia last year for the first time, I wanted to give a tip to the driver who had picked me up at the airport. To my surprise, he rejected, and ever since, it happened to me many times that Georgians rejected tips. The next day I took my first taxi ride in Tbilisi, and I was surprised that although we hadn’t agreed on a price, the taxi fare seemed very reasonable. Since I moved to Tbilisi in September, it actually never happened that a taxi driver asked for an unreasonable fare. One does not have to negotiate the price in the beginning, as one can trust in the decency of the Georgian people. In general, in Georgia nobody tries to cheat on you, and nobody tries to rip you off. The bills in restaurants only include those items you ordered, and when you get change, you do not even have to count it. Last but not least, the police do not demand to be bribed like in Morocco for not putting you in prison. In fact, here the policemen stay in the background and do not even want to check your passport. This is Georgia.

So why do crowds of tourists enter a country like Morocco to get ripped off there, but so few people come to Georgia, where they are treated friendly and fairly? More generally, how could one utilize this positive attitude of Georgians for fostering economic development?

I will look at these questions in my next blog post.

Comments

Excellent post Florian! You are right in thinking about culture and its possible link to economic variables. I too admire the traits in Georgians that you mention. Words like decent, honest, honorable come to mind. Georgians are very religious people too. I wonder if the two things are related? Religion might shape culture in several ways too. There are studies that explore the effect of religion on growth- for instance, the calvinist doctrine and economic growth in the West (due to Max Weber). Are there similar studies that explore the relation between culture and growth. But what exactly is culture? As as economist, how should I think about measuring it in a meaningful way? Is the effect of culture already incorporated in a wide range of other variables in cross country regressions? What explains the remarkable and unprecedented swiftness with which Georgia eliminated police and other low level corruption? Did the culture of the Georgian people particularly predispose them to get rid of corruption in this way? These and many other such questions come to my mind.

A great post, Florian! Every time I take a taxi in Tbilisi I run the experiment that you describe: I stop a cab and get in without saying a word on the price. Upon arrival to my destination, I would give the driver a bill of 5 or 10 GEL. In 9 out of 10 cases (and believe me, I am counting!), I would get the right change. In a few cases when I started talking to the driver (in Georgian) and explained that I am from Israel, the driver would refuse to accept payment for the ride. He would no longer see me as a passenger but rather as a guest in his country (stumari in Georgian), trying to impress me with his hospitality. Where else would you be treated like that!? I tried the same tactic in a different regional capital and instead of getting change I heard complaints that fuel is very expensive and that I should at least double the price.

I am not convinced, or rather here I would appeal to economic incentives as a plausible explanation. So far tourism in Georgia is limited, income disparities between tourists and locals are small (with most tourists coming from Armenia, Azerbaijan, Ukraine etc.), and law enforcement is strong. One could also add that tourists in Georgia are not inexperienced, in the sense that they come from the former Soviet Union, and have at least some understanding of how things work in Georgia. It's different in Morocco, where the incentives to specialize in ripping-off tourists are substantial, to the extent that one can call it a profession (con artists).

Taxis might be a good example. When I came here even airport taxis could be trusted. But last year that seemed to change, as I was quoted ludicrous prices, going up to 50 Lari for a simple trip from the airport to downtown. Fortunately that has changed, as the airport company (or so I think) stepped in, and renegotiated the contract with the taxi company. This suggests that Georgian taxi drivers are like taxi drivers everywhere.

Not to say that culture is not important, but a) culture is not fixed, but rather shaped by the environment and more imporantly b) is unlikely to be the dominant explanation here. Morocco might be a case in point, as hospitality and honesty are what one would expect from traditional Moroccan culture.

I tend to agree with Michael. We should separate the facts and interpretation. We seem to agree about the "fact" that TODAY one is much less likely to get ripped of by a taxi driver in Tbilisi compared to drivers in some of the neighboring countries and (perhaps) in Morocco. Now, hospitality is a common cultural characteristic in many Oriental countries. Thus, culture alone can only go so far in explaining difference in taxi drivers' performance and the prevalence of con artists. There must be something else about Georgia that makes it stand apart (at least today). Neither of us have lived long enough in Georgia to know how the Georgian drivers behaved in the 90s and even in early 2000s. My hunch would be that they were not as decent as today's drivers. That would suggest that the institutional reforms of recent years have had their impact and in combination with traditional hospitality created the wonderful sense of decency we are observing and enjoying today.

We do not know what was the taxi drivers' conducts in Georgia 10 years ago. It could be that it was worse than today, but perhaps that was the deviation, while today's situation is the norm. I believe that there is a long-standing cultural difference between Georgians and Moroccans, causing the propensity to cheat other people to be lower among the former than among the latter. In other instances of misbehavior, nobody would doubt that culture plays a central role. For example, it is a matter of fact that certain kinds of disrespect towards women are extremely common in certain cultures, and you only hear about it happening in these cultures and nowhere else. There are countries -- and certain parts of Western European cities -- where a western-style dressed woman can hardly walk around without being stared at, being touched indecently, and receiving "unambiguous signals" which sometimes come close to sexual harassment. Georgians don't engage in this kind of primitiveness, and I bet that they will never do. There is no political development which can account for that.

True: Political developments, short-run changes in the incentive structure etc. can play a role in shaping people's ways of behavior. Yet there is still a lot to be accounted for by cultural fundamentals.

Georgians are tight knit society and common decency is a norm. There is a Georgian saying it is better to break your head than break your name. This reflects a norm of behavior in the society and constitutes a certain code of honor that people individually and as a group (family, community, society) follow.

I think hospitality is not what we are essentially talking about. The issue is honesty and its flip side, corruption. And we do not necessarily expect honesty from Morocco or the developing world (in the transparency index some of the most corrupt countries are in the developing world). The point is that the interaction of culture and institutions can potentially produce a substantially different outcome as compared to looking at institutions alone. I thought that was the point of Florian's post (but he can explain it better).

Right, several things come together for shaping the conducts of people. Culture is one aspect among several. I would not go so far to say that culture is the only determinant of the "level of decency" in a society. In order to make a clear point, in the blog post I overemphasized the cultural aspect and neglected other factors. There is no question that material incentives, like the probability of being punished and the severeness of the punishment, also play a role.

Furthermore, the role of institutions, as mentioned by Sanjit, must not be forgotten. For example, taxi business is organized differently in different countries, and this institutional aspect matters. When taxi business is more regulated, either by some government agency or by some taxi drivers' union, usually there will be price regulations, which demands the usage of meters. When the usage of meters is the standard, as it is the case in most developed countries, cheating on taxi customers is much more difficult. I am sure that ceteris paribus , the introduction of meters will reduce the amount of taxi fraud in any country.

What we are surprised about is that in Georgia the taxi business is totally unregulated -- everybody can put a "taxi"-sign on their car's roof and become a taxi driver -- and still the level of fraud is extremely low.

All good and thoughtful points Florian (in your two replies). I will give another example. The ultimatum game (which I described in my ISET seminar this year) yields very different outcomes in different cultures. See the early AER paper here: http://www2.psych.ubc.ca/~henrich/Website/Papers/ult.pdd. There has also been a subsequent book length treatment of these results. Economic incentives are also important but a blind adherence to the principle of economic incentives is an outdated view. For instance, there has been a lot of work done on intrinsic motivation as compared to extrinsic motivation (would I work on my research any less if my salary went down a bit?). There is also a lot of evidence that high powered incentives actually make matters worse (by interfering with feelings of reciprocity). And in the US, Levitt showed that capital punishment (a huge disincentive for crime) does not work. This is not to argue that economic incentives are not important- surely they are. But there is a much more nuanced view out there.

Florian's post deals with an important set of issues. And this central one of the way economists model human behavior as if all humans around the world are essentially the same - and respond to the calculus of rationality - has many pitfalls - one set of which is exactly as he states here - the absence of beliefs, morals, cultural values, which influence the way people behave in reality.

First and foremost, there is a need to clarify something here. Not all "economists and economics" are guilty of this false way of looking at human behavior. Note Douglass North's contribution to the past several decades addressing precisely this set of issues, and many others, including myself, who would not be so crass as to accept this type of approach (almost like a nice crisp formula). If people were so rational, wars would easily be avoided because the majority of the world would simply invest a little to arrest war mongers as far as I have seen the calculations....How would we explain social wars??? if not for whipping up people despite showing them the bill?

I would point out also that originally economics did not view people this way. Jeremy Bentham, one of the early utilitarian types - simply stated in his Principles of Morals and Legislation that people were generally guided by pain and pleasure (ie modern costs and benefits much more broadly defined). The theory Florian is referring to uses a very narrow concept of this - including treating humans as rational at the expense of emotional - and this is standard in neo-classical economics - which is widespread, but largely unable to explain much human behavior.

The other side of the coin, however, is that there is an underlying current here that could and should be retained. To divide people up into rational societies and less rational ones is a mistake - like medicine, there are many commonalities across societies that does allow for using a single discipline like economics to examine choice behavior - if it is done carefully. Especially if we assume at the outset that people do not have full information, and the way they look at costs, and what they think are benefits (desireably outcomes) can be shaped by culture, religion and belief.

I often wonder if neo-classical economists and neo-cons are not guilty of effectively wearing theoretical burkas... or hijabs.

It¡¦s truly a nice and helpful piece of information. I¡¦m satisfied that you simply shared this helpful information with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

I find this blog post very surprising as having travelled all around the caucuses / Turkey / Russia __ I have found taxi drivers in Georgia to be some of the least honest anywhere in the world. I would advise any travellers reading this post to take care and double or triple check the fare before getting in a taxi anywhere in Georgia.

Dear Edward, that is incomprehensible to me. In the six years that I have been living in Georgia, I was cheated by taxi drivers less than five times, and I am going by taxi on a daily basis. Perhaps we have different definitions of what constitutes cheating? Do you consider it cheating/dishonesty if you pay a little bit more than locals?