Competitiveness is an elusive term that can mean different things to different people. Moreover, there is no consensus on how a country can become competitive. For instance, South Korea’s economic breakthrough in 1960s and 1970s was arguably promoted through government-induced investment in (and protection of) particular sectors of the economy (e.g. steel, ship building and electronics) which were deemed to be potentially “competitive”. Alternatively, rather than picking winners (something bureaucrats are said to be bad at), governments could promote competitiveness by liberalizing trade, reducing taxation, red tape and corruption, and ensuring a level playing field among investors. Likewise, while everybody agree that the quality of “human capital” – a well educated and healthy labor force – is a key to competitiveness, there may be disagreement on whether the government should target specific skills (say, vocational training, IT and engineering – Georgian government’s darlings as of late) which are considered a “binding constraint” for economic growth or whether educational choices would be best taken care of by Adam Smith’s invisible hand (the argument, again, is that bureaucrats don’t know better).

Whatever the strategy, for countries like Georgia and Armenia, which are not rich in natural resources, achieving higher productivity and competitiveness is likely to depend on their ability to increase the quantity and quality of foreign direct investment (FDI). For international businesses to set up shop and invest in Georgia there has to be a sense of economic opportunity related to, for instance, geographic location on a trade route from Europe to Central Asia, easy access to a large regional market, well-trained and disciplined labor, and availability of cheap resources (water and hydroelectricity). The policy environment – e.g. macroeconomic stability, “ease of doing business”, low taxation levels, low trade barriers, and corruption – also plays an important role.

Perhaps less obviously, there may be something about the country and its people that would attract investors despite a lack an immediate economic advantage. The innate decency of Georgian people (see Florian Biermann’s post), their warmth and hospitality to foreigners (“stumari”), beautiful landscapes and great food, are some of the factors that come to mind. After all, other things being financially equal (or even slightly unequal) it makes sense to develop a long term relationship with a country you like…

Finally, certain cultural factors and traits might deter potential investors from making a long term commitment despite an obvious economic opportunity. One such factor – on the cons list of any expat living in Georgia – is bad driving manners. Tbilisi today boasts one of the lowest crime rates in the world, yet it is not a safe city. It is not safe to walk around Tbilisi given the absence of sidewalks. It is not safe to cross Tbilisi roads given the lack of respect for pedestrians’ rights. And it is not safe to drive in the city given the reckless (bordering on suicidal) behavior of many Georgian drivers.

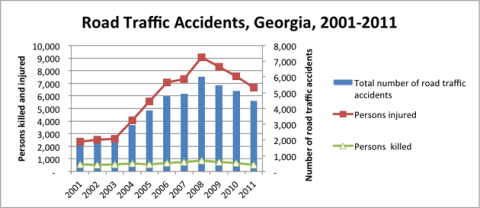

The good news is that the situation is gradually improving, at least as far as statistics are concerned. After 2008, which was the worst year in Georgia’s traffic history, the number of car accidents and the cost of these accidents in terms of human life have been on a steady decline. Yet, much of this improvement could be attributed to investment in inter-city infrastructure and (most recently) enforcement of seat belts. To the detriment of tourists, potential investors, and the Georgian people at large, the culture of driving in the cities appears to be resilient to change. It is my hunch, however, that bad driving manners could eliminated in a fortnight, just like petty corruption was defeated in the early years of Saakashvili administration. All it would take is political will, stricter regulations (higher fines) and tougher enforcement. The results would include lives saved and a greatly strengthened competitive image abroad.

P.S. With the elections coming up in early October, I wonder whether any political party would care to include this idea in its program…

Comments

Nice post, everything is so true. I just want to draw your attention to the fact that there is no part on the street where you can cycle safely. I think for promoting healthy life and from the ecological point of view it is really important to develop the infrastructure that is necessary for safe cycling.

Not to go far, I am sure any of you feel the extreme of walking even on Zandukeli street. Cars don't consider you as a person and what any foreigner with whom I walked there mentions is the crazy driving manners of the cars. Everyday coming back to ISET from LOBIANI SHOPPING I thank to god that I survived.

While it is true that there is some disagreement over what competitiveness is, how to measure it, and therefore how to improve it, there is fairly widespread agreement on the general idea that it is a fancy term for "productivity." One of the reasons competitiveness is unclear is that productivity - what it means, how to measure it, and how to improve it, and for what ends, is not clear.

Basically, a region that improves its "competitiveness" is able to produce whatever it is that it produces as lower real cost than before. This enables the region to potentially compete more effectively in global markets (as well as domestic) for selling its products (whether they be final or intermediate goods and services). If it is more able to do this, it should attract AND RETAIN more economic activity than it would otherwise.

The fear is that a region which fails to improve its competitive position (seek ways to produce more efficiently) will lose out to those who will - and lose economic activity - which translates into lower investment, lower incomes, fewer, less diverse, job opportunities, and they will have fewer resources for both public and private consumption. Ultimately, competitiveness (productivity) is seemingly well linked to a region's ability to remain prosperous.

The issue here with driving is a good case for showing that achieving higher levels of competitiveness is more complex than simply removing red tape, lowering taxes (which is far more controversial), or improving infrastructure for production. A region's most important "productive" asset is ultimately its labour supply - they are the ones who use the roads, move the goods and services, turn the machines on and off, etc. This fact is very often forgotten. And as a result.... people forget that making the country a nice place to live helps to attract and retain labour, and it can help attract and retain innovative and creative labour necessary for enhancing productivity (people like Richard Florida seem to get it, but so did Adam Smith - see not just the Wealth of Nations, but the Theory of Moral Sentiments, his more important book and contribution to society!!).