For a long time, it has been a taboo to criticize the Orthodox Church in Georgia. Quite recently, however, the clergymen themselves lifted this taboo by publicly carrying out their conflicts. The visit of Pope Francis in September 2016 sparked a plethora of mutual accusations. Archpriest Davit Isakadze was against the Pope’s visit and blamed the two other Archpriests Toedore Gignadze and Aleksandre Galdava for being sectarians and church enemies. These accusations were rebutted by Archpriests Levan Mateshvili and Ilia Chigladze, who called for protecting Teodore Gignadze and Aleksandre Galdava from these attacks.

The open confrontation culminated in February 2017 with the allegation that Archpriest Giorgi Mamaladze, serving as the deputy head of the Patriarchate’s property management service, attempted to poison the Georgian Patriarch’s personal secretary with cyanide in order to gain a greater share of the power within the church. The main witness to Mamaladze’s alleged poisoning attempt, his friend and relative Irakli Mamaladze, testified that the priest had asked him for providing potassium cyanide in exchange for a good position within the church. Irakli Mamaladze also reported that Giorgi Mamaladze intended to poison other high ranking clergymen and that he was backed by a group of supporters, among them other clergymen. Ominously, Archbishop Peter Tsaava talked about a shadow rule in the Patriarchate and named those clergymen who were intentionally or non-intentionally involved.

For the first time, internal turmoil of this kind became public, potentially threatening the reputation of the Orthodox Church, which had been flourishing over the recent decades.

HOW THE CHURCH BECAME SO STRONG

Early in its existence, the Soviet Union turned Karl Marx’s anti-religious views (“religion is the opium of the people”) into official policy, when atheism was prescribed to the Soviet citizens. Yet this atheism was superficial and did not take hold in the hearts of the people. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the successor countries were not only shaken by dramatic economic, political, and social transformations, but there was also an ideological vacuum. In some post-Soviet countries, like Georgia, religion could partly fill this vacuum.

In the case of Georgia, the revival was indeed significant: while in 1970, only 47% of Georgians were affiliated with a religion, in 1995 that number had gone up to 80% of the population (Froese, 2004). One of the reasons behind this resurgence was that in the aftermath of the Soviet breakdown, Christianity had been perceived as part of the traditional pre-Soviet cultural environment and a crucial component of ethnic identity. In this way, religion was a bridge to pre-Soviet times and created cultural continuity with pre-Soviet Georgian history. Consequently, it was not surprising that the first President of Georgia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, while fighting for independence, always emphasized the Orthodox Church as the symbol of national identity and unity. Moreover, as the newly gained independence started with severe crises (two civil wars in the 1990s, corruption, high crime rates, economic and social insecurity), the Orthodox Church became for many the bedrock of stability and unity and a beacon of hope. In this time, the weak state and its leaders tried to become affiliated with the church in order to raise their own legitimacy and reputation in the society, e.g., in 1995, the government of the second president Eduard Shevardnadze granted the Georgian Orthodox Church legal recognition, various privileges, and direct financial assistance from the state budget.

Reputation and influence of the church did not cease after the Rose Revolution. The new government of the United National Movement tried to move the discourse towards a form of civic nationalism (which included the defence of religious freedoms and pluralism) and curb “religious nationalism”, but this was not very successful. While the state subscribed to an agenda of modernization, reforms, and liberal values, many people felt left behind and therefore kept their traditional allegiance to the Orthodox Church. It seems that the Orthodox Church, as an ideological rival to the UNM government, rather strengthened its status as an institution of high moral authority and trustworthiness.

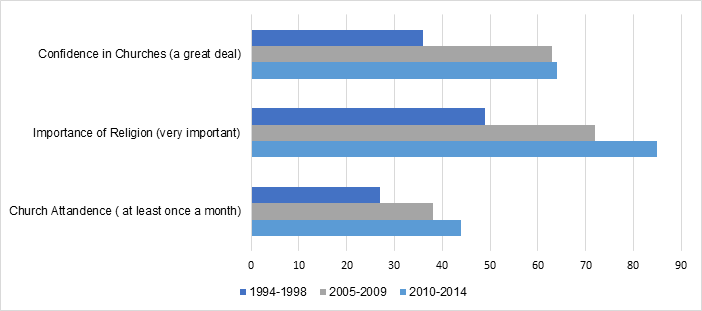

Statistics reveal the same positive trend that was described above. According to the World Value Survey, all of three variables confidence in churches, importance of religion and church attendance have been continuously increasing since 1994. Interestingly, church attendance is not as wide-spread among Georgians than confidence in the church, showing that the importance of the Orthodox Church extends beyond religious feelings and practices. In Georgia, also the non-religious trust the church! This was already pointed out by Charles (2009), who argues that Georgia is a somewhat atypical case, as in many countries, like Poland, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Brazil, church attendance is more wide-spread than trust in the church. This idiosyncrasy might make the Georgian Orthodox Church more vulnerable to the internal conflicts.

AND THE FUTURE?

According to Avner Greif, an eminent economist at Stanford University, institutions are optimally adjusted to the exogenously given conditions prevailing in a society. At the same time, the institutions themselves may lead to a change of the parameters under which they operate (he calls such parameters, which are influenced by an institution, “quasi-parameters”). For example, the Roman Republic was a great success and led to enormous conquests and expansions of the Roman Empire. Yet, this successful development required an ever more powerful military apparatus, which finally, led by Julius Caesar, caused the downfall of the Republic and its replacement by a dictatorship. Similarly, medieval guilds in Europe may have fostered industrialization and in this way caused the demise of the crafts and trades that were organized in these very guilds. In both cases, successful institutions had an impact on the parameters under which they operated, and at some points these institutions were not optimally adjusted anymore to the circumstances they had created themselves. Could a development like this also affect the Georgian Orthodox Church?

A poor church without influence or wealth does not yield incentives for its members to start power struggles. There is nothing to be gained anyway. Success, on the other hand, may give rise to infighting, as there is more to fight for. In this sense, what we see may be the consequence of the church’s unprecedented success in the last 25 years. Will the church keep up to this challenge and survive it without damage? Only God knows.

Comments

Georgian church: a victim of own success?

I am not sure. The high esteem and wealth enjoyed by the Georgian church are evidence not of its own success, but of the spectacular failure of the liberal narrative (democracy, human rights, etc.) to unite the Georgian people. Those left behind - perhaps the majority of the Georgian population - find it very difficult to believe in a liberal story of which they are not really a part. And it is not Putins fault.

The Avner Greif story (briefly mentioned in the last paragraph), is a very interesting one. Indeed, successful institutions can (and should!) work themselves out of a job. For example, one can say that Georgias anti-corruption campaign was so effective, that Georgia does not really need an anti-corruption agency (not incidentally, all highly corrupt countries maintain anti-corruption agencies). But Greifs arguments do NOT apply here. The Georgian church may indeed go through a phase of infighting as part of its growing pangs, but it wont be out of its job any time soon, not before Georgias secular institutions (education, healthcare, business and government) start doing their job.