In the old Soviet movie, “Once Upon a Time Twenty Years Later,” a mother of ten who bought a lot of clothing and food in a local shop was suspected of being a speculator by the shop administrator, who immediately called police as the woman left the shop. The woman survived arrest after it was discovered that she bought so many goods exclusively for her big family, and not for resale or so-called speculation.

In Soviet times, the word “speculator” had an extremely negative meaning. People who were deemed to be speculators could be jailed if the allegation was proven. Today, speculation is not prohibited as such, but the word “speculation” or “speculator” is often used in a rather negative sense.

Speculation is possible in all kinds of markets; most frequently, it happens in the markets for stocks, bonds and currencies. Although agricultural commodities also quite frequently become the target of speculators. Speculation is particularly prevalent in wheat and sugar markets. Cocoa and coffee are also subject to speculation from time to time. Interestingly, garlic became the target for speculators quite recently when at the end of 2016, garlic prices skyrocketed. Bad weather in China, where more than 80% of the world’s garlic exports originate, led to low harvest expectations and created incentives for traders to gain on a price difference in the future. Heavy rains and snow damaged the harvest and reduced the supply. Many traders rushed to buy garlic. and such speculative buying increased prices. Finally, the lack of supply and high prices resulted decreased exports from China.

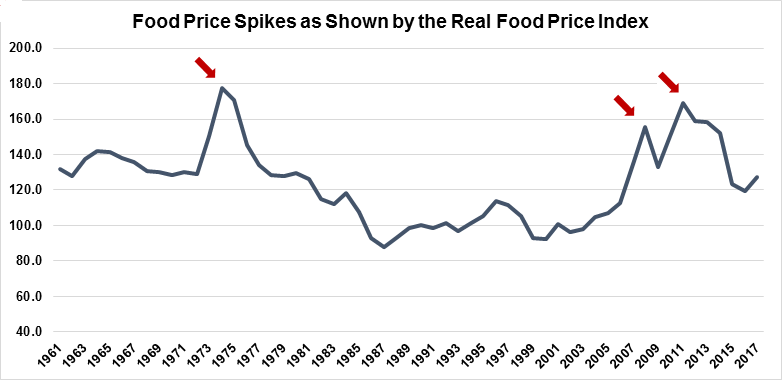

Speculation is one of the causes of food price spikes, which have happened a couple of times during the last 50 years. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the most notable food price increases happened in 1974, 2007-2008 and 2010-2011.

Although speculation is never the only reason of a spike, its role is quite substantial. Given that in the short-run, food prices are usually determined by production (supply), stocks, oil prices, exchange rate fluctuations, trade policy (e.g. export restrictions) and speculating, if the price change is very sharp like the almost 40% increase in the Food Price Index in 2008 compared to 2006, speculation should never be ignored (Wahl P, 2009).

BUT WHAT IS SPECULATION?

Speculation is a very old phenomenon which appeared on food market as early as the 17th century, when farmers sold their harvests to traders before they were harvested. Speculation is defined as the purchase of an asset (a commodity, goods, or real estate) with the hope that it will become more valuable at a future date. Although the definition is relatively simple, there is a debate on whether speculation is somehow different from investment. Some economic theories like neo-liberalism, do not see any difference between those two, and consider speculation to be a form of investment, whereas others argue that investment and speculation differ by their nature and effects on the economy.

In contrast to neo-liberalists, and similarly to many other economists, Wahl P. in his briefing paper “Food Speculation, the Main Factor of the Price Bubble in 2008” argues that the difference between speculation and investment is that investment generates value added, which can be used to increase business sustainability, while speculation just benefits from price differences and creates no additional value. Another difference is that when investment fails, the assets (building, machinery etc.) still can be used in the future for other profit-generating activities, while there is nothing left after speculation fails. In terms of effects on the economy, Wahl states that the system is considered to be highly unstable when wealth is accumulated by speculative actions which do not add anything real to the economy.

HOW DOES SPECULATION WORK?

The usual way is as follows: farmer negotiates a fixed price to be paid to him at a later date with a trader and signs a contract – a derivative, which is called a future. This kind of speculation is called a commercial trading, and is considered to be relatively “good speculation” because on the one hand, the contract provides security for a fixed price to the farmer, and at the same it transfers the risk from the farmer to the trader. On the other hand, if a trader sells his derivative to a miller, then part of the risk is transferred from the trader to the miller. Such trading is beneficial for the miller because it ensures a stable supply. Since the actual price of a commodity is not known in advance, later, when the future is due, the price might be either higher or lower than price fixed in the contracts with the farmer and miller, thus resulting in a gain or loss for the parties. In spite of the price difference, the trader still earns some money, because derivatives are not free and the fee is part of the trader’s income. Because of this fee, the price of a commodity is higher than it would be if the trade had occurred directly between the farmer and the miller. Thus, although this kind of trading is relatively positive, it still causes price increases, and this is not the only issue; commercial traders have less incentive to increase the productivity of other actors in the value chain. Traders prefer to have shortages of agricultural commodities and price volatility because this simply makes them rich. Some of big traders even have their own weather stations to better predict harvests, and thus prices.

|

While this kind of commercial trading is linked to production, the activity of index funds, which is yet another category of traders who trade with a basket of commodities, is driven purely by changes in stock exchange indices, and is extremely pro-cyclical. Index funds whose basket contains up to 20% agricultural commodities are usually the main drivers of food price bubbles (trade in an asset at a price or price range that strongly exceeds the asset's intrinsic value), which is a major problem of speculating. After a crisis on the financial market, many index funds turn to commodity markets, causing an increase in food prices.

Thus, both types of speculation, good and bad, lead to increased food prices, which threatens food security and puts one of the basic human rights – access to food – at risk.

HOW TO DEAL WITH SPECULATION?

State guarantees are one of the alternatives to speculation on food markets. Although one has to keep in mind that when a state guarantees some price, this is yet another form of state subsidy and thus a typical market distortion and, which puts pressure on a limited state budget.

Even though legendary investor and best-selling author Doug Casey argues that successful speculators are low-risk, rational and unemotional, if there are too many of them acting at the same time, the possibility of price bubbles emerging in the market is obviously higher.

Comments

Futures contracts are a useful tool to mitigate risk, and are commonly used by graingrowers, feedmillers, and producers of beef, pork and chicken to protect themselves against wild swings in commodity prices that may affect their profitability. A large proportion of such instruments are used by institutions not directly involved in food and agribusiness, which improves the liquidity of such instruments. A side effect can be that the herd effect amongst investors may cause irrational shifts in underlying commodity prices, but these tend to be self-correcting and short term in nature.

We can see the long-run trend in real food prices over the past 55 years is relatively flat; production efficiency has grown substantially, post-harvest wastage has been reduced and logistics is more efficient, and this has offset additional demand from a growing global population and increased consumption of animal protein worldwide.

There are now hundreds of times many more speculators involved in the food market, via futures and warrants, as well as via shareholdings in listed food companies, than in the 1960s. Money tied up in speculative instruments related to food is many times greater than 55 years ago. Yet food prices in real terms remain the same, more or less. A tripling in trade of agricultural derivatives in the past decade has been accompanied by only 20% increase in food price in real terms, so the causal association is not very strong.

I witnessed first-hand the effect of food price controls in Indonesia in the late 1990s. Food traders hoarded foodstocks rather than sell inventory at a loss, so food shortages swept the country. Unscrupulous traders bought food at the below-market controlled prices and smuggled it to Singapore in massive quantities to sell at global prices, exacerbating food shortages even further. The end result was not a happy one for consumers nor traders.