Below are Google Maps images of two rural communities (A and B) in Georgia. Please click image to enlarge.

Readers of this blog are welcome to propose their answers to the following multiple choice questions:

Q1. East or West?

a) A is in Eastern Georgia, B in Western Georgia

b) A is in Western Georgia, B is in Eastern Georgia

c) Both are in the same part of Georgia

Q2. Land distribution among households

a) Land is more equally distributed among households in A

b) Land is more equally distributed among households in B

c) There is no difference between A and B in terms of land distribution

Q3. Household income distribution

a) Income is more equally distributed among households in A

b) Income is more equally distributed among households in B

c) There is no difference between A and B in terms of income distribution

Q4. GDP per capita

a) GDP per capita is higher in A

b) GDP per capita is higher in B

c) GDP per capita is roughly equal in A and B

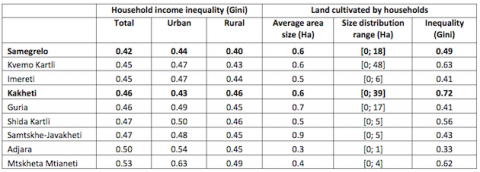

Given the very large share of rural population in the total, land is a major political economy concern for Georgia. Land privatization of the early 1990s resulted in a highly fragmented land ownership structure with most farmers receiving roughly equal plots of about 1.2ha. Over time, the process of land consolidation has brought about significant changes in the initial allocation of land, affecting agricultural productivity and income distribution.

Looking at today’s data on land cultivation, we find major differences among the various Georgian regions. Some regions went through a process of land consolidation; others are still extremely fragmented. In Adjara, for instance, all households surveyed by GeoStat in 2011 cultivated tiny plots of less than 1ha while the average was 0.3ha. Conversely, in Shida Kartli, the largest plot was about 50ha, very large by Georgian standards.

Table 1: Cultivated land and income inequality in Georgia, 2011

A TALE OF TWO GEORGIAN REGIONS

The main wine producing region and historically the buffer (“Sakartvelos pari”) against Persia and other Moslem invaders, Kakheti (represented by rural community A) is an interesting case. To provide locals with some degree of protection against the enemy, Kakhetian villagers huddled together in dense villages surrounded by cultivated land. Demand for protection was also a cause in strengthening and sustaining the rule of local lords (tavadi) whose lands the villagers were working for much of the region’s history. The facts that Kakhetian lands remained consolidated under the lords’ control made them an easy target for expropriation by the Bolsheviks who turned Kakhetian villages and the lands around them into collective kolkhoz farms.

The kolkhoz farms were destroyed and looted in the early 1990s while the lands they occupied were divided among their individual members. However, the availability of large contiguous parcels suitable for grape growing – a very lucrative business until 2006 – quickly made Kakheti an attractive target for investors, local and domestic. As a result, Kakheti is currently the leader in land consolidation. In 2011, a half of Kakhetian households owned plots smaller than 0.2ha; at the same time, a relatively large number of farmers managed to acquire or rent additional land beyond the originally allotted 1.2ha; some of the privately owned farms are really large by Georgian standards, up to 40ha. The Gini coefficient measuring inequality in cultivated land in Kakheti is 0.72, higher than in any other region.

An important point to note is that land consolidation has not brought about any visible efficiency gains at the macro level. Despite government efforts to artificially prop up grape prices in recent years, Kakheti is currently one of the poorest Georgian regions and the only one with income inequality concentrated in the rural areas.

An exactly diametrical situation is observed in Samegrelo (represented by rural community B). Local villages are spread out, with each house sitting in the middle of a fairly large plot of land – not exactly ideal from the land consolidation point of view. With ample rainfall, soft climate, and specialization in crops that are not particularly scale-intensive, Samegrelo is the smallholder farmer paradise. While also here land consolidation was unavoidable, the largest plot included in the 2011 GeoStat survey had about 18ha. Most importantly, Samegrelo is characterized by the lowest income inequality across all Georgian regions, among both urban and rural households.

Comments

The path dependence in plot sizes is fascinating. Perhaps those living in Kakheti are also much more willing to sell their land because of their historically weak ties to it.

The historical differences in land ownership and foreign interventions across regions may have important implications for how well land markets can function in different areas. Those areas in which there has been a long tradition of land ownership may have landowners who are much more reluctant to sell their land than those landowners elsewhere, even holding the potential for land consolidation constant.

Indeed, I would also expect Megrelians to have a stronger attachment to the land. For the same reasons (tradition), they may be better at farm management and marketing. On top of all that, selling one's land AND house is a very different proposition compared to selling the land only.

The data we had on land consolidation are very partial since they surely do not include the largest parcels consolidated by wine producers and others. Have just heard about an Iranian-owned business that bought 5,000ha in the Gurjaani area (Kakheti) for corn and wheat production. What we can tell from the data is that a lot of Kakhetian farmers no longer have any land to speak of.

I agree with you. Selling just a land and selling a land with a house on it are very different things. I personally am owner of 0.5 Ha land in Samegrelo with my ancestors house in the middle. Regardless the fact that I am not going to live there, I assure you I will not sell it ever

Maka, this is the meaning of having roots!

ჩვენ ვლაპარაკობთ სასოფლო-სამეურნეო მიწაზე, თუ საკარმიდამოზე: 0,2ჰა არ არის ს/ს დანიშნულების - ის მხოლოდ ეზოდ და ბოსტნად თუ გამოდგება,at liest ხეხილის ბაღისთვის. ასეთი მიწების გათვალისწინება ეკონომიკურ კვლევებში რამდენად მიზანშეწონილია, ხომ არ მახინჯდება სტატისტიკა? საქართველოში მიწების კონსოლიდაციაზე მეტად აქტუალური უნდა იყოს მოსავლის შენახვა, ლოჯისტიკა და შემდგომი გადამუშავება , მაშინ მიწების დაქუცმაცების უარყოფითი ეფექტი მეტ-ნაკლებად გადაილახება. გლეხებთან რომ გაფორმდეს შესყიდვის ხელშეკრულებები და აეწყოს ერთიანი სასაწყობე-ლოჯისტიკური ქსელები რაიონების ან რეგიონების მიხედვით - მცირემიწიანობის პრობლემა მინიმუმამდე შემცირდება. ამ პროცესში ბევრი ქალაქელი (ქ-ნ მაკას მსგავსად) შეიძლება ჩაერთოს და მათთაც გამოიყენონ შთამომავლობით მიღებული 0,5ჰა მიწები ეკონომიკურ პროცესში და რაღაც მოსავალი მოიწიონ, მაგ, თხილი და ა.შ., ანუ ისეთი კულტურები, რაც ნაკლებ ყურადღებას და დროს ითხოვს. I am first time, guys, participate in the discussion. If I have done something against law - sorry about this! I will try my best next time in English.