There is a Georgian joke that goes: “Relatives are the people you see whenever their number changes”. In other words, relatives all tend to gather when any of them gets married, gives birth or dies. As a result, we frequently observe Georgians organizing mass gatherings to either celebrate or mourn numerical “changes” in their families. While there is a recent trend among the wealthier and better educated people to switch to more intimate, smaller events, the poorer rural people continue to arrange Georgian supras of monumental proportions.

A FORM OF CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION?

When attending Professor Omer Moav’s lecture on Economic Growth which classified large Indian weddings as a form of “conspicuous consumption”, I started wondering whether the Georgian tradition of mass family events can also be considered in the same manner. Moav defined conspicuous consumption as consumption of goods which serves to show off one’s economic prowess without providing any positive economic benefits. He further argued, based on economics analysis, that it is the poor who are more likely to engage in acts of conspicuous consumption in order to pretend that they are not who they are (poor).

Prima facie the grand Georgian supras seem to fit this definition: the poor who organize mass funerals could have invested their scarce resources in much more profitable ways, for instance by investing in own health or education for their children. Organizing funeral feasts for hundreds of guests by the poor could be thought of as a form of showing off. What also makes these events akin to conspicuous consumption is the fact that this tradition is increasingly losing favor with the wealthier and better educated Georgians.

IS IT SOMETHING ELSE?

Despite many similarities there is one feature that clearly distinguishes these Georgian mass gatherings from typical cases of conspicuous consumption: the fact that guests, including relatives, neighbors and other acquaintances are expected to make a sizeable financial contribution. This kind of arrangement makes these events more like an insurance scheme, rather than “bling-bling” consumption.

A Georgian family would normally keep a detailed record of guest contributions at an event such as a funeral or a wedding, being prepared to reciprocate in case of need. Given the long-term nature of the resulting financial commitment, it is not surprising that wedding and funeral contributions are enshrined in the Georgian tradition. One might even perceive such payments or gifts as a membership “fee” for being a part of a “club” brought together by kinship or social bonds.

However, I would argue that the emergence of this type of club behavior is driven by the insurance motive: you help others when they are in need and thus expect to get help when it is needed for you. As I found out, similar community-based insurance schemes in the form of funeral contributions can also be found in the likes of Ghana, Ethiopia, Tanzania and other developing countries.

WHY INSURANCE?

Insurance is a form of risk management that is primarily used to hedge against the risk of a contingent, uncertain loss. People crave for safety when facing uncertainty, and death is a rather uncertain event (at least as far as timing is concerned). The ancient Romans are said to have been the first civilization to use insurance to cover the costs of funerals. Today, people who do not want to overburden their offspring with funeral expenses may take life insurance. A community-based insurance through the tradition of funeral contributions may be a handy alternative.

Some categories of people are less likely to purchase a formal life insurance. These are: the poor who cannot afford an insurance product; people belonging to strong and supportive family units; people who do not place trust in financial institutions and would rather participate in a community-based insurance arrangement with people they trust (relatives, neighbors, etc.), or people who have superstitions associated with death and are reluctant to consider any associated arrangements in advance.

Weddings also pose a financial challenge for families and are difficult to plan sufficiently in advance. As financial markets are yet to come up with a wedding insurance (at least in Georgia), poor families have the choice of having a large, community-supported wedding; a modest, affordable wedding; or no wedding at all.

Economic analysis has it that the poor are more likely to opt for funerals and weddings financed by community-based insurance schemes and will therefore tend to arrange mass social gathering. Similarly, the more educated families (who have fewer superstitions about death), and higher-income individuals, are more likely to switch to market-based insurance (or save).

FROM FUNERAL CONTRIBUTIONS TO LIFE INSURANCE

There is a lively debate within Georgia whether the tradition of “qelekhi” – the feeding of guests before, during or after a funeral – should be retained or not. For the older generations, this tradition is meant to show respect to the deceased. At the same time, many younger people may consider such meals and associated drinking to be a direct insult to the mourners. For many, compassion from hundreds of people is not a necessary condition for the mourning of a loved one. Moral considerations about “qelekhi” aside, funerals would have been far cheaper without this tradition. In any event, more modest qelekhi attended by a smaller number of guests, would help cut the costs incurred by the relatives of the deceased.

The tradition of qelekhi is more likely to survive in large, tightly knit, poor communities where it plays a more important insurance role and where defection (refusal to contribute) is more costly to the individuals involved. In wealthier and more educated urban circles, families are more likely to free themselves from the need to accept or make funeral contributions. By relinquishing this communal bond, such families undertake to finance own family contingencies with their savings or with the help of insurance.

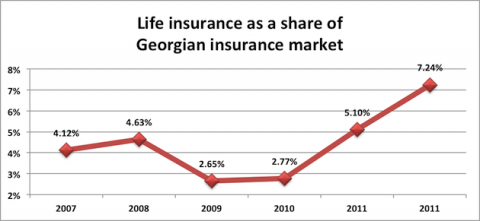

As Georgians grow wealthier over time, they will be more likely to switch from informal community-based insurance to life insurance products offered by insurance companies. This has been the trend elsewhere in the world, and to some extent may be already happening in Georgia, judging by the share of life insurance in total insurance.

Comments

Very nice post! I look forward to test your theory when we will get survey data! :-)

Thanks. Let us know whether the test will be passed or not

What struck me at a Georgian wedding (I've been only to one wedding as I am apparently not a member of any family club) is the amount of food on the tables. Food gets brought dish after dish, and is accumulated in layers. At the end of the feast my table was covered by a mountain of plates and food that no one was able to even look at. And then came the desert: barbecue!

Interesting!

However, Eric's comment implies that in addition to the insurance motivation, conspicuous behavior plays a role...

very interesting article Nino, it seems like you continued Maka chitanava's concern about outdated Georgian traditions (see http://www.iset.ge/blog/?p=730 ) as regards to Eric's comment, I think, there is no place for a conspicuous behavior but rather it is a hospitable action.

Georgia is not an exception when talking about exsessive festivities around funerals and weddings. This is equally true for many nations and as the author rightfully points out it is extinquishing over time. And there is a reason for that. At least for Kyrgyz people - once absolutely nomadic nation - they had to have tribe-wide causes to bring together isolated families of shepherds spread across vast territories. And weddings as well as funerals could not have served the cause any better. Naturally, such gatherings should have been worth multi-day travel along the mountain ranges and rapid rivers.

And that includes overly abundant food on the tables. Apart from some element of showing off the wealth of the host family (quite a natural aspiration) it also served very practical, survival purpose for those who would be packed with food for their travel back to homes.

Very interesting comparison, Nazim! Never thought of the importance of weddings and funerals as a means of keeping a nomadic people together.

Chinese do the same. The guests guestimate how much the dinner may cost and top it off some so the host generally ends up not having to really pay for the meal. As people normally give cash gifts, there is usually a small army of family counting the cash gift and settle the bill. It is not deemed considerate to pick a venue too expensive for your guests

The cultural homogenization which can be seen almost everywhere makes the world a more boring place. In general, I would be happy to see cultural peculiarities and customs of different people also in the long run. Unfortunately, some old customs may have been useful in the past, but today they are harmful and problematic. Arranged marriages among relatives, honor killings, and patriarchalism are examples for that. There seems to be a general tendency that societies in which traditions are observed very strictly tend to yield less opportunities for their members for personal self-fulfillment, which can potentially be very tough for those affected.

When a society transforms from traditional to modern, it is a big challenge to keep those customs alive which enhance people's well-being, while getting rid of those which are harmful and make life unpleasant. The family gatherings clearly seem to be of the first kind, and should therefore be preserved.

Although we are in the 21st century, many societies have severe problems to get rid of malignant traditions, which are often backed by religious beliefs. Georgia seems to be doing and to have done relatively well in the transformation from traditional to a modern society, though also in Georgia certain traditions seem to be unnecessary and inefficient (e.g. the early marriage age of Georgians).