This blog post is a sequel to “Price of a Woman: Economic Rationale behind Marriage Payments in Georgia”. I recently found very interesting data about bride prices in the Georgian highlands and the North Caucasus, which I am now going to share with you.

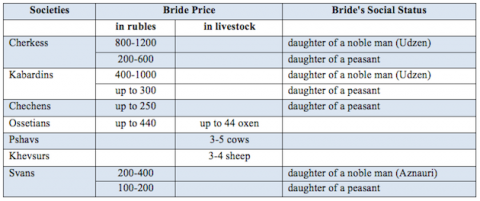

Payment to a bride's parents was widespread in the Georgian highlands and the North Caucasus. This custom was rooted in local traditions and everyone obeyed it. Bride prices were either paid in money or its equivalent in livestock, most commonly in oxen. The price would vary according to the social standing of the bride and personal qualities such as her beauty and age, and whether she was a widow or a single woman. Table 1 below represents data about bride prices in the Caucasus after the Russian Empire’s conquest in the first half of the 19th century.

Table 1. Bride Prices in the Georgian Highlands and the North Caucasus

Prices are given in rubles, the national currency of the Russian Empire at that time, or in livestock. For lack of data, I was not able to convert all prices to the same measurement. I obtained the ox-to-ruble “exchange rate” for Ossetians only but decided not to use this exchange rate to convert other prices.

Differences between the Georgian and the North Caucasus bride price

Bride prices in monogamous societies like those of the Pshavs, Khevsurs and Svans were mainly determined by the economic value of women and their scarcity. In the Moslem Cherkess, Kabardin and Chechen societies the custom of polygamy resulted in greater demand for women and higher bride prices.

Ossetians are a complicated case as historically they were Christians, but some of them adopted Islam in the XVII-XVIII centuries. We should thus use caution in interpreting the Ossetian data since we do not know whether it relates to Islamic or Christian families.

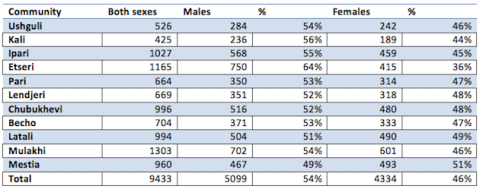

We lack reliable data concerning the three Georgian ethnicities – Svans, Pshavs or Khevsurs, but my hunch is that bride prices were highest among the Svans. According to available historical accounts, Svanetia has always had the largest disparity between the male and female populations. Table 2 shows the distribution of Free Svanetia population in 1887 (the earliest date for which data are available).

Table 2: Ratio of males and females in Free Svanetia (adapted from Teptsov V.J., “Svanetia”)

The 1926 census carried out in Khevsureti, another mountainous region of Georgia, shows that the total population of the region was 3,472, with females exceeding the male population by about 200 (source: Makalatia S., “Khevsureti”, 1935).

Bride prices among the mountain people of the North Caucasus were strictly regulated by spiritual leaders or at community gatherings. There are several documented examples of such decisions. In 1866, a special meeting was held in the three communities of Northern Ossetia, where the standard bride price (“irad”) was decreased and fixed at 200 rubles. It was also stated that if a groom had no means to pay for his bride, he could pay with labor – being obliged to work for the family of his future wife for eight years! Similar things happened in Chechnya in the mid-19th century where, according to the order of Imam Shamil, the bride price was reduced until it reached the minimum of two cows. In 1879, members of the Ingush republic passed a verdict setting the maximum bride price at 105 rubles. These examples can be viewed as “price ceilings” on brides to ensure that poor grooms had the opportunity to get married. We do not possess similar information on bride price regulation in the Georgian highlands.

As discussed above, in the Georgian highlands, bride prices were lower than on the other side of the Greater Caucasus mountain range. Moreover, they were partially offset by special gifts (called “Satavno”) families gave to their daughters upon marriage. Satavno represented a bride’s personal capital, ensuring her rights in her new family. It is interesting that the sickle (“Namgali”) and scythe (“Celi” or “Satibi”) were two necessary things given as Satavno in the highlands of east Georgia, reflecting expectations concerning the brides’ future role in agricultural production.

About two centuries ago, the bride price custom was quite common ago everywhere in the Caucasus. Since then, however, it practically disappeared in all monogamous societies. In such societies, bride prices reflected economic incentives – they compensated families for the loss of a valuable worker. And they vanished with the weakening of the underlying economic incentives. In polygamous societies, on the other hand, being grounded in religion and culture, this tradition lingers on in the 21st century. Even today, one can find a recommended bride price of 40,000 rubles ($1,300) on the official webpage of the government of the Russian Republic of Ingushetia.

Thus, although I am unable to give a definitive answer to the question I posed in my previous blog post, I have managed to refine my hypothesis: traditions based on a merely economic rationale change or disappear with the change in economic circumstances; traditions that are grounded in religion and corresponding social norms may be better able to defy time and economic rationality.

P.S. For those interested in the peculiarities of the Georgian marriage traditions; in analyzing marriage as a social contract, representative not of a private but a communal affair; in looking at enforcement mechanisms and punishments for breaking such contracts; in comparing male and female socio-economic values, or in any other related issues, I would recommend visiting the National Library of Georgia as many of the invaluable works of the late19th and early 20th centuries are not yet available online.

Comments

In Georgia the market mechanism seems to work. At least in the highlands, the market reacted to the shortage of women by implementing a "bride price" custom. Interestingly, not everywhere the market seems to function. In some provinces of India, like Punjab, you have a really low female/male sex ration at birth, caused through selective abortions and killings of female babies. In one Punjab region, in 2001 there was a female/male sex ratio at birth of just 0.75 (http://www.prb.org/Articles/2008/indiasexratio.aspx). Yet this doesn't lead to the introduction of bride prices. To the contrary, you still have expensive dowries, which are a primary driving force behind the skewed sex ratio. In your first article, you hypothesized that dowry practices are caused through little demand and bride prices are caused through high demand for female labor. You therefore conclude that dowries will disappear when the value of female labor increases, for example through education possibilities. Your hypothesis sounds reasonable, but I am surprised that the people in traditional societies consider partnerships between men and women primarily as an economic enterprise, completely ignoring the non-economic impacts on human well-being resulting from such partnerships. Where is the romanticism in these societies? The terrible rape case which occurred in New Delhi recently (http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/wp/2012/12/18/gang-rape-of-a-girl-inside-a-bus-in-new-delhi-raises-outrage-in-india/) shows the social consequences of having a shortage of women.

Thank you for this post and your interesting blog.

I've recently had experience of bride prices. I've been involved with a charity in western Kenya for a few years. Polygamy in this rural society is still commonplace. According to the locals the current price for a bride is 12 head of cattle: 6 male and 6 female and a goat for the feast, small payments may also be made to uncles.

I haven't been able to visit this year, however my swiss girlfriend who runs the charity and is currently on site in Kimilili, told me over Skype that last week she received a marriage offer and a bride price of 30 head of cattle!

I'd like to think that this is confirmation of my very good taste rather than market forces. I'm delighted to report that my girlfriend, although flattered, declined the offer!

Thank you Maka for your post, a very enjoyable read.

William Ellis

Dear William and Florian,

Thank you for your interesting comments.

@Florian : Related to Romanism. I believe Romantism was involved to some degree, but one had to pay very high price for that. Breaking a marriage promise was not easy, but was possible and you had to pay fine for that. For example in Pshavs If a marriage promise was broken by the bride side his family had to pay 15 caws (3-5 times more than brideprice). In case she had married another person, her family was freed up from the payment and her husband had to pay instead of them. So you needed to be rich to have a luxury of Romantisn. In addition, Georgian highlands had very distinct and interesting traditions of Tsatsloba and Stsorperoba, which were characterized by high degree of Romantism and with restraint from sex at the same time.

i couldnt believe this. like in India, or any other part of world here illitracy or you can say absence of women empowerment exist there exist this customs. Womens are not mere animal which can be traded like that. Like Mr. Florian said rape in India. If there are less women, that doesnt mean you have the right to rape the women (sorry Mr. Florian). in marriage proposal.

in marriage proposal.

In India where women is worshiped as a Goddess and raped also i dont co-relate this thing to women population.

Yes money can buy women but cant buy love.

It is very interesting that William Ellis Swiss friend is lucky enough to receive 30 cows

Here in Georgia, or any part of world women in today world know her value and price. I am in Georgia since one year and was also earlier having one girl friend in past but my marriage proposal was turn down by the girl and her family. Though she use me in every sense from making me dance to her tune,and also above the limits of sex. According to me God has gifted the girl the power of make people dance. And yes we can say in the last Everything in this world is for sale but one should be ready to offer a good price for everything.