INTRODUCTION

The Namakhvani Hydropower Cascade is a system of two plants with a total capacity of 433 MW and potential yearly generation of 1496 mln. kWh (around 13% of the total generation in 2020). The HPP has been designed for the river Rioni, to be built just 20 kilometers or so from Kutaisi, one of the largest cities in Georgia. The project is operated by the Norwegian Clean Energy Group, with 10% shares, and the Turkish industrial conglomerate, ENKA Insaat ve Sanayi AS, holding 90%. It is also linked to a 15-year Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) from the Georgian government, indicating that the electricity it generates will be purchased by the government for eight months a year (excluding May, June, July, and August) for the first 15 years of the plant’s operation. During the remaining four months, the ownership will be free to market the electricity either domestically or abroad. The construction was launched on 1 March 2021, with completion planned by August 2024.

In recent months, the Namakhvani hydro power plant has become one of the most discussed topics in Georgian society. The project has also been protested several times by thousands in the center of Kutaisi since their first mass protest on 28 February, the day before the preparatory works started.

Most of the criticisms raised seem to be rooted in the perceived lack of transparency during the negotiation and preparation phases of the project. The protesters raised doubts about the fairness of the legal background of the project. They assert that the Georgian government might be giving away extremely valuable national reserves (lands and hydro resources) for free, without clear future benefits for the country. They also expressed concerns about the possible threat to the population several kilometers down the Rioni river if the dam is realized. The protesters further claim that no reliable geological or seismological assessment for the proposal has been provided to the public, and – as the region is seismically active – any miscalculations could destroy people’s lives and property during a natural disaster. The demonstrators subsequently highlighted that the Namakhvani, and all similar projects, should be planned with the involvement of local communities, and that closed doors negotiations between the central government and foreign companies are unjust with respect to affected populations. Their concerns about affecting the microclimate and ecology were also raised. Finally, the protesters expressed doubts regarding the project’s true necessity for the country’s energy security.

Recently, a meeting between the main protesters and the chief policymakers was conducted. The result being that both parties recognized that they each have an obligation to prove the accuracy of their positions. This is surely a step in the right direction. Only through an open and constructive dialogue, based on objective evidence, can strategically important – but highly impactful – actions, like the realization of large energy projects, be carried forward.

Although the issues raised push well beyond the economic rationale behind the choice to authorize the Namakhvani HPP construction, this blog will approach the discussion from an economic angle, exploring whether – and to what extent – the HPP satisfies the energy needs of the country. We will take this chance to look ahead to potential energy challenges, and to seek a possible way forward, keeping in mind the lessons learned from the Namakhvani controversy.

CONCERNS OF ENERGY SECURITY

The International Energy Agency defines energy security as: “the uninterrupted availability of energy sources at an affordable price.” With this in mind, there is no doubt that Georgian energy security issues are persistent (with electricity being one of the most important forms of energy), as a negative electricity generation-consumption gap has persisted since 2017 (Figure 1). The Enguri HPP rehabilitation project has also demonstrated how much Georgia depends on a single HPP. The first months of 2021 marked both record high generation-consumption gaps and imports. The net export equally follows the generation-consumption gap trend.1 Bearing in mind continuing depreciation of the Georgian lari, increased imports are likely to cost more and more as time passes. Moreover, Thermal Power Plants (TPP) operate on natural gas, which is also imported (although not included in electricity import statistics), thus the import-dependency of the electricity market is even larger than it appears from simply gauging the monthly electricity balance.

Figure 1. Annual Consumption-Generation Gap and Net Imports

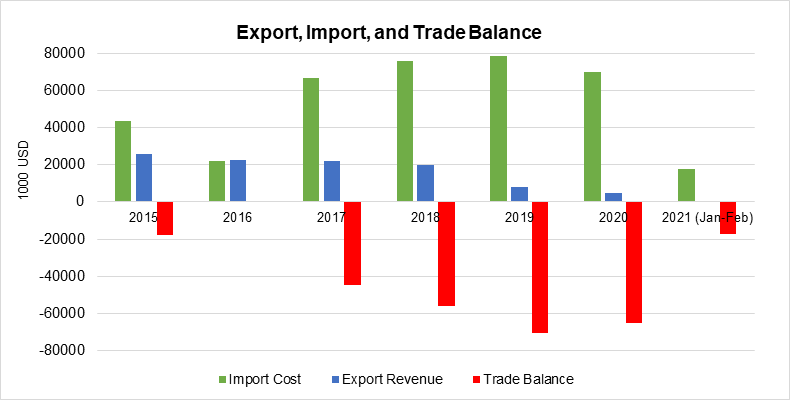

The total cost of imports is a crucial statistic – as imports have been increasing over time so have their total associated costs. Starting from 2017, the electricity trade deficit increased until 2019 (Figure 2). Although 2020 was an exceptional year for the entire world, and even though the lockdowns negatively affected energy consumption and imports, the trade deficit remained high.

Figure 2. Export, Import, and Trade Balance

The main question seems to be, can the Namakhvani HPP contribute to Georgia’s electricity security? According to the Georgian Energy Development Fund, the expected annual generation of the HPP will equal 1496 mln. kWh. While trade statistics reveal that the net imports for 2019 and 2020 were 1383 and 1456 mln. kWh, respectively. However, we should not overlook Thermal Power Plant (TPP) production (2821 mln. kWh, or 25% of total production in 2020), which is based on imported natural gas. These available estimates on electricity demand moreover suggest that it will keep increasing over time. Therefore, rationale for increasing domestic generation using renewable resources is plainly evident. The southern Caucasus region is still subject to periodical turmoil – most of the population clearly remembers the winter of 2006 when the Russian Federation stopped its gas export to Georgia. Consequently, being less dependent on imported energy offers a huge advantage in the region. Any resource imported from foreign countries can also be used as future political leverage. Being closer to self-sufficiency in this sector thus might be valuable and essential for sustainable long-term development, but this will require a steady increase of the renewable generation base, especially considering the projected upcoming increase of electricity demands.

Among the various criticisms levelled, one concerns the price of 6.2 cents per kWh that the government agreed to pay for electricity from the Namakhvani HPP. This guaranteed price level has been decried because it is substantially higher than current import costs. If the HPP operates at full capacity and sells all 1500 mln. kWh of its electricity, the total cost the Georgian government would have to bear would equal roughly 93 mln. USD, which is clearly greater than the total trade deficit in previous years.

The Minister of Economy and Sustainable Development, Natia Turnava, has been highlighting – however – that the property tax the company will pay equates to 30 mln. USD per year, in addition to other revenues generated from the Namakhvani HPP operations. Therefore, the taxes the company would pay are significantly greater than the difference between the import expenses and the Namakhvani costs. Moreover, the Ministry expects the project to employ up to 1600 people during its realization; although this is likely to drop substantially after construction of the plant. According to ENKA, the local population will also be given priority during the recruitment process.

Among the other potential benefits generated by the plant, ENKA cites the amount of CO2 emission that could be averted every year (750,000 tons) thanks to the Namakhvani HPP. This would consequently help Georgia meet the Paris Climate Agreement goals.

CONCLUSION

Economically speaking, the Namakhvani HPP could play a role in overcoming Georgia’s future energy needs challenges. Electricity is one of the most important aspects of energy security and the Namakhvani HPP could significantly contribute to production (generating an amount equaling the yearly gap the country currently faces). The Namakhvani is also expected to contribute to the local employment, tax revenue generation, and a reduction in CO2 emissions.

On the other hand, any request for the government to address the concerns of the populace, especially those most heavily affected in the Rioni valley, about the environmental, political, and economic impacts of the project, is legitimate.

The United Nations and the Paris Agreement maintain a clear position on hydro power – it is an essential form of renewable energy and is necessary, together with other renewable sources, for the world’s sustainable development. This is certainly also the case in Georgia, where the demand for electricity is expected to grow substantially in upcoming years.

Even if the Namakhvani HPP is accomplished, more investments in renewable generation – hydro, solar, wind, and biomass, among others – will need to take place to ensure the country’s energy security. It is, therefore, imperative that the parties involved – the government, in particular – learn from this experience in order to understand how to prevent conflicts, diffuse tensions, and achieve shared solutions.

One key step is to ensure that the population is fully and credibly informed about the benefits of the future projects. ENKA published a research series on Namakhvani (seismicity, environmental impact assessment, hydraulic calculations, etc.), but it does yet appear to address all the protesters’ fears, potentially as ENKA is regarded as an interested party. These concerns might have been better tackled if the potentially negative economic, social, and environmental consequences of the project had been thoroughly assessed by a research team, one appointed jointly (and thus trusted) by both sides. This team could have then documented and shared its findings with the public, together with plans to mitigate any problems.

While adopting such an approach for future projects might require some additional preparatory work, and increases planning costs, a more transparent and participatory approach would help achieve a broader consensus and generate further support for clearly beneficial projects. Developing a culture of constructive negotiation between the people and investors is also an essential step towards ensuring the faster realization of large and strategic energy projects and improving the investment climate, thereby increasing the attractiveness of the country to potential investors.

Ultimately, everyone should agree that transparency, inclusivity, and evidence-based decision-making are of the utmost importance when planning large strategic projects like the Namakhvani HPP and, more generally, when defining the country’s path towards energy security. There is much at stake, and the animated discussions over the Namakhvani HPP, and the lessons that can be learned from it, provide a great opportunity to move more decisively in the right direction.

[1] The difference between these two variables is caused by losses from generation plants, self-consumption of the plants, and transportation costs. The difference is almost constant and ranges between 450 and 500 mln. kWh per year.

Comments