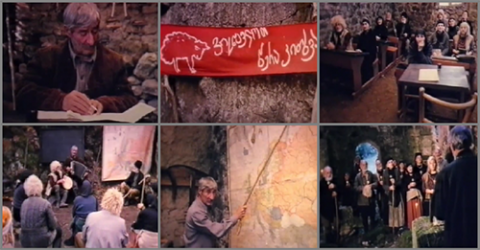

When I think about the lack of human capital in Georgian agriculture, I am reminded of the 1997 Georgian movie “The Turtle Doves of Paradise”, directed by Goderdzi Chokheli. In a Soviet village, an ex-priest decides to teach basic knowledge to old peasants. He wants them to learn to read, write, and elementary calculations skills.

The movie addresses a problem that, fortunately, has been completely eradicated in the last decades. Nowadays, virtually all people living in Georgian villages are able to read and write (and probably also to multiply, subtract, and divide). According to the CIA World Factbook, Georgia has a literacy rate of 99.7%, ranking on place 13 out of 216 countries, before advanced economies like Switzerland, Sweden, and the United States.

While rural illiterateness was fought successfully, agricultural workers of today suffer from different yet equally problematic knowledge gaps.

TRACTOR DRIVING AND PLANT BIOLOGY

Two years ago, I was confronted with the problem of a lack of human capital among Georgian farmers for the first time when I met with representatives of authorities from Qvemo Qartli, Samegrelo, and Mtskheta-Mtianeti. One of the representatives told me that the municipality had bought tractors several years before and lent them to the villagers. Yet soon afterwards, all of them had become dysfunctional, due to mishandling of the tractors by their users.

Later the government provided new tractors to the same municipality, but, given the experiences made previously, the municipality decided not to lend new tractors to unskilled operators. Thus, many expensive machines remained idle in the service centers as there were no knowledgeable famers to use them.

The problem, however, reaches far beyond operating tractors. In advanced countries, agriculture is highly sophisticated business. Modern agriculture requires its practitioners to attend university and obtain degrees in agricultural engineering, a field that combines disciplines like plant biology and mechanical and chemical engineering. Without employing such knowledge, Georgian agriculture cannot catch up with countries such as France, where the average agricultural worker creates 30 times more value than an average Georgian agricultural worker.

Fortunately, as far as educational capacities are concerned, Georgia is in a relatively good position. Multiple universities in Georgia offer degrees in agriculture and related fields. The Agricultural University of Georgia is arguably the foremost institution producing agricultural experts, yet also other universities outside Tbilisi, like Gori University, I. Gogebashvili Telavi State University, and A. Tsereteli Kutaisi State University, offer relevant programs.

A VICIOUS CYCLE

Why is there a shortage of human capital in the agricultural sector then? Five words tell the whole story: low salaries and low prestige.

The Georgian agricultural sector is caught in a kind of vicious cycle. As the chart shows, in 2012 the monthly average salary in agriculture barely exceeded 400 laris. In the Georgian economy only tourism, fishing, and education yielded lower salaries than agriculture. But that is not surprising – what else would one expect in a sector that is so poorly developed?

As a result, there are no incentives for young people to pick up a career in agriculture, further impeding the development of the sector and causing salaries to be low also in future.

It should be mentioned that there exist some well-paid jobs in agriculture. These are often provided by foreign employers, like investors engaging in Georgian agriculture and international organizations with an agenda related to agriculture.

In addition to low monetary incentives, there is also a psychological problem. Like other professions desperately needed by the Georgian economy (engineering, math, and natural sciences), also jobs in agriculture suffer from low prestige among young Georgians.

VOCATIONAL TRAINING AS A WAY OUT?

Starting in 2006, the Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia (MES), in collaboration with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), established vocational education in seven Georgian towns: Gori, Kachreti, Ambrolauri, Akhaltsikhe, Telavi, Akhmeta, and Senaki. Nowadays, there are plenty of colleges offering vocational training programs that emphasize applied knowledge in fields like agronomy, veterinary sciences, and bee-keeping.

The system works by vouchers: the state grants those students who choose to study in accredited vocational colleges a 1000 GEL voucher. According to MES: “State vouchers will be granted to socially vulnerable students, schoolchildren who completed the basic level of education in the current academic year, and the twelfth graders who wish to pursue a professional education after graduating from secondary school”.

While promising on a general level, it is not clear whether the program successfully addresses the human capital needs of the agricultural sector. The Georgian vocational education report for 2012 states: “The list of voucher financed vocational education training courses gives clear priority to occupations in the area of construction, followed by ICT, tourism, and hotel-restaurants, and contains limited number of programmes in the area of agriculture and business.” In addition: “The share of students registered in programmes of the agricultural group is very low (below 0.8 % of total), which acts counter the refreshed attention of the government for the sector.”

The idea of vocational training is appealing, and there may be specific problems that need to be solved for it to make a difference for Georgian agriculture.

In Chokheli’s film, an idealistic former priest taught people how to read. Today, the problem of illiteracy has disappeared. There is reason to hope that with the right tenacity, in the long run also the level of agricultural knowledge will improve among Georgian farmers.

Comments

"As a result, there are no incentives for young people to pick up a career in agriculture, further impeding the development of the sector and causing salaries to be low also in future"- very good point which needs to be addressed somehow.

Recently I attended very interesting presentation of a study about intercultural education research in primary grades of Georgia. Among other things authors have analysed school textbooks of grades 1-5 and finding are very relevant for this blog. Analyses show that there several episodes in textbooks which raise concerns with regard to stereotypes associated with territorial settlements. The books are designed in a way that show ONLY city lives -characters of the textbooks are MAINLY urban kids; actions take place in the URBAN AREAS; ONLY grandparents live in the villages. Information about the life in the village is very few and is limited describing just few activates. I believe this, at first glance, tiny issue will add it’s weight to the problem of low prestige of agriculture and internal migration to urban areas in the future. Maybe we have to think about these stereotypes that influence our young generation? Can this be one of the long run solutions of the problem?

Great comment, Maka! Stereotypes are an important part of the story. Of course, the agricultural sector has to become much more capital and knowledge intensive for it to offer attractive (productive) employment. That however cannot happen without the presence of smart and education people, hence the vicious circle aspect of the problem. For a while, the Georgian government strategy of "squaring" this vicious was about bringing foreign investors. Not any more, so it seems

Very interesting point. Thank you Maka.

In countries with technically advanced agriculture sectors (like USA, Canada, EU or Japan), family farm operators and staff usually do NOT possess a university degree. Perhaps less than a third of farm owners are university-educated, most have degrees in a non-agricultural discipline, and indeed it is not necessary to be a graduate to be an effective commercial farmer. Many such family farms are worth $5 million or more, and turn over millions of dollars in a year. They commonly use the services of contractors who have university degrees, such as veterinarians, agronomists and engineers. A degree in agronomy, animal science, agricultural engineering or veterinary medicine does not teach you to be a farmer (although if you already have farming skills from your family farm, it can greatly enhance them).

Corporate agribusiness tends to employ more graduates in its management structures, or in other cases fund employees' university education as part of the remuneration package.

The presence of a local technical college, for farm owners to do short courses for narrowly defined skills, and certificate courses for somewhat broader technical disciplines, is an important resource for the rural community, be it in a developed country or in rural Georgia.

Salaries for farm workers will rise when they accumulate skills that make them more productive. Such workers become attractive to rival employers and the competitive pressure on wages is inevitable. The employer's conundrum is always, "What if I spend the money on training my employee, and he leaves?". The answer is, "What if I don't spend the money on training him, and he stays?".......