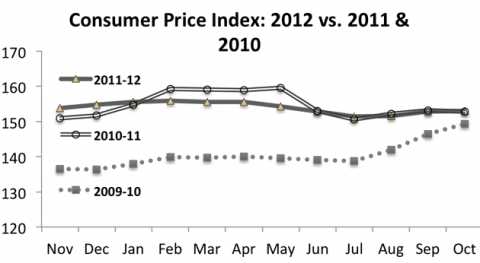

During the past 18 months, Georgian consumers have been enjoying an unprecedented period of price stability. Ever since May 2011, when inflation peaked given the state of frenzy in the global commodity markets, inflation has literally come to a halt: since early 2012, monthly inflation rates are fluctuating around the zero trend. In fact, Consumer Price Index (CPI) is slightly lower today (153) than in January 2012 (153.8), and only 0.1% higher than in October 2011 (152.8).

THE STORM IS COMING!

A spate of worrisome news is hitting the Georgian media since the second half of October. Workers’ protests spread across Georgia. Poti Port – a key transit hub - is paralyzed by a strike. Some 1600 coalminers strike in the Georgian Industrial Group-owned Tkibuli mine – the largest in Georgia. Tbilisi bus drivers went on strike demanding a raise in their salaries. IDPs and vulnerable families intruded into buildings in Tbilisi and other Georgian cities, including Zugdidi and Poti.

By and large, this type of workers’ behavior could be expected given the social agenda of the winning Georgian Dream coalition, an agenda that focused on equality before the law, but also jobs, improved protection of labor rights, higher wages, pensions and other social benefits. The vigorous political campaigning and election slogans were necessary in order to win the elections, yet they created expectations that now translate into labor protest and civic action threatening to undermine the very macroeconomic stability that is needed for investment, job creation, and economic growth. And without strong economic growth the new government will not be able to make good on its promises, potentially throwing the country into political turmoil.

Georgia is thus facing a classical dilemma of democratic politics: how to keep the (poor) majority happy without threatening economic stability and sustained growth. In the coming months and years the Georgian nation will learn – by-doing – whether it has made enough progress – economically and politically – to be able to fully enjoy the benefits of democratic governance. As Yaroslava Babych wrote in the ISET Economist Blog this week, “Democracy may be likened to a sophisticated instrument that has the power to facilitate growth in the hands of those who know how to use it. At the core of mature democracy is the aspiration to actively participate in the process of decision making, the ability to take ownership of the political and economic agenda of the country. Therefore, I am not surprised that democratization often produces the best outcomes in societies that are already well-to-do.”

Ironically, much of the economic development and statehood building (which many now deny) achieved by Georgia since the Rose Revolution can be attributed to a complete lack of democratic checks and balances on the Saakashvili administration. With a constitutional majority in parliament, a servile judiciary, and control over central TV stations, the executive branch of government under Saakashvili was free from the need to appease the populace. Moreover, it had the business community on its knees. Treated with the carrot of preferential treatment and the stick of intrusive tax inspections, businesses kowtowed to (formal and informal) price controls on politically sensitive goods (grapes, flour) and contributed to UNM political campaigns or extravaganza projects.

Free from the need for political compromises, the government was able to squeeze social spending and boost investment. For instance, the official Georgian Ministry of Finance presentation from 6 September 2012 proudly states: “Government expenditure is more heavily weighted towards capital spending than among peers. This allows to implement infrastructure measures which enhance Georgia’s competitiveness and create sustained employment opportunities”. Note the use of “sustained” (as opposed to “immediate”).

The MinFin presentation further boasts “a rapid and sizeable fiscal consolidation ahead of schedule”. Indeed, Georgia managed to reduce its fiscal deficit from -9.2% in 2009 to a meager -3.6% in 2011, marking a very fast recovery from the double whammy of the August 2008 war and the global financial crisis. How was it achieved? By keeping the lid on the so-called “recurrent spending” – essentially salaries of state employees, including teachers. In the technical jargon used by MinFin this achievement is described as follows: “Limited exposure to recurrent spending as reflected in the operational surplus (5.2% of GDP in 2011) of the general government eases the task of compressing overall spending over the medium term.”

WILL THE GEORGIAN DEMOCRACY BE ABLE TO WEATHER THE STORM?

Having survived a peaceful and orderly transition of power, Georgia is already a much more democratic country compared to any previous period in its history. It has a divided (pluralistic) parliament, pitting the winning coalition against a strong opposition party armed with a solid ideology. Yet, looking ahead, the real challenge is to sustain this political achievement: address the mounting demands for greater redistribution while not falling into the trap of populism; and rule while implementing democratic deepening in such crucial spheres as media and judicial independence.

In its own right, liberal democracy is hardly the magic growth pill. If mismanaged, it may unravel into chaos and/or drift towards authoritarianism (as has been the fate of many European democracies in-between the two world wars). Yet, if handled well, democracy can produce great results, economically and otherwise. After all, there are other reasons for people to value the freedoms that go with democracy: the freedom of speech, religion, or assembly. Georgia deserves a system of governance that provides citizens with a sense of dignity, not often experienced in our part of the world. Not by bread alone, as it were.

Comments

Highly interesting analysis of the problems facing Georgia under the new government. Indeed, one problem of the democratic system is that the politicians have an incentive to always make promises, which in turn raise the expectations in the population. In the Soviet Union there was no such problem: At least under Brezhnev, nobody believed the socialist propaganda anymore, and consequently there was no general expectation that the economic situation was going to improve (at least this is what I believe about the Soviet psyche). In a democracy, on the other hand, there is always this fundamental believe in an improvement of the economic situation. Economists play their role in forming these exaggerated expectations by claiming that the right economic policy can lead any society to economic prosperity. Yet there is no proof that this is true: There are some case studies of countries adopting certain policies and improving economically, but by and large the economic well-being of a country 100 years ago is a very good predictor for that country's economic status today.

So shouldn't we economists rather curtail excessive expectations and emphasize the well-being of a society which can be achieved without economic growth?

In this regard, at its end the article rightfully stresses that democracy has many benefits in itself, regardless of its impact on economics. Living is a democracy is just much more pleasant than living in a dictatorship. The general well-being of a population may in the end not depend so much on the material wealth as we economists tend to believe.

But, Florian, why blame the economists? First, they are all two-handed species (on the one hand, on the other hand, etc.).

)

)

Second, while there may be a few optimists here and there, there are probably more economists who completely fail to see the full half of the cup, predicting that the crisis is (always) just behind the corner (and once in a while they turn out to be right

Thus, either one economist's prediction is cancelled out by another economist's prediction, leaving the public's expectations unaffected. Or, one and the same economist mumbles something along the lines of "one the one hand... but on the other hand", which has about the same impact on the public's mind.

The only persons I would blame are the overzealous politicians and, us, naive voters.

Do economists really have two hands? That's how they seem themselves... but in reality? Paul Krugman - two hands? Nouriel Roubini -- two hands? In particular in development economics, people are highly opinionated: They all know the precise recipe which will end the misery of the underdeveloped countries. Take Andrei Shleifer's crusade for his agenda, or -- less visible in the media -- this Icelandic guy Thorvaldur Gylfason, who in his book on growth tells you exactly why some countries did well and others didn't (not a pleasant read if you sympathize with Socialism and the like).

All of these economists believe that in principle, all countries can have material prosperity like Europe and the US. If it doesn't happen, then it is because their proposals weren't implemented. This belief in the unlimited possibilities of economics raises expectations in the population, doesn't it?

I feel that economics can become even better if we do not promise to every society wealth and prosperity (if it follows our advice), but instead open our minds for other kinds of welfare, not growth and material wealth. Possibly, a country like Georgia would do better if it would not even try to go the same way as Europe and the US but instead would head for some kind of "non-material" economic development.

There are interesting ideas of this kind already, like the "Gross National Happiness" index which they introduced in Bhutan. But that's a great topic for my own next blog-post... :-)