“Don’t rush to judgment on Georgia” was the title of a recent article by Michael Cecire in Foreign Policy (FP). Written in an apparent reaction to “Georgian Dream shows its dark side” (FP, November 29), and “Georgia’s government takes a wrong turn” (Washington Post, November 28), Cecire’s piece attempts to provide a more objective account of the situation. According to Cecire, “the Western outcry has been much too hasty. Ultimately, it's not the arrests [of senior UNM officials] themselves that will test the new government's commitment to democratic ideals and the rule of law so much as the Georgian judiciary's commitment to transparency and due process. On that count, issuing harsh judgments now would be premature, and could aggravate already raw feelings in Tbilisi, where many feel that the West was much too close to the UNM and often too passive to its excesses.”

A similar note is struck by Anna Dolidze and Thomas de Waal in “A Truth Commission for Georgia” (Carnegie Endowment for International Piece, December 5) who shrewdly point out that the furor around the recent arrests of UNM officials, “both in support of and in opposition to them, reflects that the rule of law is probably the most critical problem for present-day Georgia. In fact failings of the rule of law could be called the “dark side” of the 2003 Rose Revolution, which unfortunately—and despite the efforts of nongovernmental organizations such as the Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association and Human Rights Watch—received less attention than the government’s anticorruption and economic reforms.” Dolidze and de Waal focus on the need to bolster the rule of law in Georgia and recommend that the new government take a “transitional justice” approach by forming an objective “truth commission” to deal with the past.

There are many reasons for Georgia and its friends around the world to be concerned with the strength of its fledgling democratic institutions. For one thing, rule of law and property rights are, indeed, key elements of a free democratic polity. What I would like to emphasize here, however, is that there are also very important economic reasons for Georgia to worry about rule of law and property rights. In particular, a recent study by the ISET Policy Institute (Michael Fuenfzig and Yaroslava Babych, June 2012) identified weak property rights as the binding constraint for investment and Georgia’s future economic growth. Incidentally, this study contradicts the main findings of a similar “constraints analysis” exercise that has been previously undertaken by the Georgian Prime Minister’s office at the time.

Fuenfzig and Babych argue that as a result of reforms enacted after the Rose Revolution, Georgia did very well in almost all indices concerned with the formal aspects of “doing business”, such as the number of days it takes to register business, the tax and customs procedures, the lack of petty corruption, etc. Exceptions were indices that measure property rights protection and political stability, broadly interpreted. As they explain “Property rights and political stability do not only encompass laws designed to guarantee and protect property rights, but also the ability and willingness of the government to evenly enforce and to respect these laws; the stability of the government itself; the stability of institutions, and the absence of potential internal or external conflicts.“

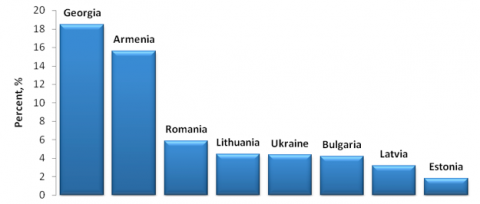

The risks associated with weak property rights are reflected in data concerning Georgia’s financial sector. For instance, Figure 1 compares the average real interest rates among a group of transition economies, including Georgia, for the period between 2000 and 2011. Among the developing countries of Europe and Central Asia, Georgia has had one of the highest real lending interest rates. In 2011 the real lending interest rate was 15.3 percent – up from 14.4 percent in the previous year.

Georgia’s real lending interest rate was not only high compared to other developing countries in Europe and Central Asia, but also compared to all countries in the world. According to the World Bank, in 2011 the Georgian real lending interest rate was the eighth-highest in the world, only below the real lending interest rates of the Uganda, Papua New Guinea, Gambia, Kyrgyzstan, D.R. Congo, Brazil, and Madagascar. This is particularly striking given that real lending interest rates in the major economies were at record low levels. It is also not an aberration given that already in 2007 Georgia had the eighteenth highest real lending interest rate in the world.

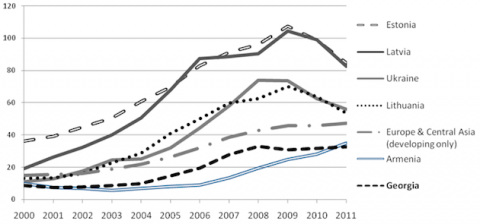

As shown in Figure 2, the availability of domestic credit to the private sector was also significantly below the regional average. While the share of domestic credit to the private sector in GDP was only 32.8 percent in Georgia in 2011, the comparable number is 47.4% percent for a group of developing European and Central Asian economies. Credit to the private sector as a share of GDP has been increasing since 2003, but it came to a stop in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Although GDP growth has since then recovered, credit to the private sector has remained stagnant.

With this data in mind, one can have a clearer appreciation of the damage inflicted on Georgia by the negative press it has been receiving in recent weeks. Right or wrong, perceptions of reform reversals and poor protection of property rights would be a major impediment for Georgia’s continued economic revival and growth. As Babych and Fuenfzig put it “firms and entrepreneurs will be less likely to invest, and if they will, their investment will be of the high-risk-high-return type. Banks will charge higher real lending rates, will be more likely to require collaterals, and will shorten the maturity of the loan.”

The new government thus has a task that is both easy and difficult. To boost growth it needs to ensure continuity. At the same time it has to break with the past as far as property rights and the rule of law are concerned. Foreign and domestic investors have to be convinced that the new administration is doing everything in its power to adhere to the rule of law and, indeed, make this issue a top priority for future reforms.

The The Growth Diagnostics study for Georgia is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Eric Livny and do not necessarily reflect the view of USAID, the United States Government, or EWMI.

Comments

Dear Eric, I think your article is marvelous! But I have lived for 15 years in Romania and I believe situation is quite different from what you describe...

[...] I’m looking into both of these investments at the moment. Fascinatingly an ROI of 20% doesn’t attract local investors as the local real lending interest rates are in the region of 18% – 20%. If it is possible to borrow money internationally at low interest rates, we may just have a winner! Real Lending Interest Rates average 2000-2011 (Source World Bank taken from http://www.iset.ge/blog/?p=1100) [...]

A strong article, but I think that the conclusions derived from the data on interest rates are somewhat speculative. In the article high interest rates are considered to be indicators of weak property rights, but high interest rates can have many reasons. Arguably the interest rates depicted in the diagram were those which were paid by banks to depositors. Were there any defaults of Georgian banks? I do not know of any. If banks have a history of paying back reliably, why should a foreign investor care about property rights in the real sector of the economy? As long as the bank doesn't go bankrupt, the money will flow back to the investor. Do the investors anticipate that the bank's default risk is higher due to a lack of property rights? That is possible, but it would require the investors to be very well informed about the internal situation in Georgia.

If the investors are not well informed, there would be an alternative explanation for the high interest rates, not drawing on a lack of property rights. Perhaps the returns on invested capital in Georgia are particularly high, yet foreign investors hesitate to bring their money to Georgia because they are not well informed about Georgia's relatively positive internal situation. Lacking information, foreign investors might perceive Georgia to be in the same group as less reliable countries of the former Soviet Union (Uzbekistan and the like).

Though being speculative, I agree that the interpretation given in the article is quite appealing in light of Michael's and Yasya's study.

Florian, I agree that there is an element of speculation regarding the link between high interest rates and property rights. However, there are three points I would like to make:

-- First, this interpretation is not mine, but Michael and Yasya's.

-- Second, their analysis is quite a bit more comprehensive. For instance, they look at credit to the private sector and the interest rate spread. It is on this latter indicator that Georgia really leads the world.

-- Third, poor property rights are indeed suggested as a driver of risk perceptions and interest rates. Yet, much of the risk reflected in high interest rates is not bank or project-specific. Rather it is country risk (as reflected e.g. in Georgia's investment ratings). It is not about a firm or bank defaulting on its obligations but rather, for example, the option of Georgia getting involved in a civil war (because of high levels of income and wealth inequality and the lack of experience in managing a successful democratic transition). The possibility of another conflict with Russia was (and still is) in the back of investors' minds. Yet another type of risk is concerned with the rule of law (independence and professionalism of the legal system, or lack thereof) and the state conduct in dealing with businesses. As we are now better aware, the latter was a real concern for both foreign and domestic investors.

Finally, the fact that domestic businesses borrow at the going interest rates does indeed suggest that Georgia offers high return investment opportunities, mainly related to trade and transportation services. Otherwise, people would not borrow. The problem for Georgia is that other opportunities to invest that do not offer a quick buck -- but are very important for Georgia's long-term growth, productivity and wages -- are not acted upon. For instance, who would want to invest in a high fixed cost manufacturing project that offers a 8-10% return on capital?