Anyone who has seen an old American classic “Best Years of Our Lives” (1946) probably remembers the scene where one of the protagonists, Al Stephenson, a banker who just returned from war in the Pacific, tells his incredulous colleagues: “Our bank is alive. It’s generous. It’s human. We are going to have such a line of customers seeking – and getting - small loans, that people may think we are gambling with the depositors’ money. And we will be. We will be gambling on the future of this country”

This speech neatly summed up the prevailing mood of the post-war times – rebuilding an economy after a long stagnation or war requires an element of calculated risk. Without banks willing or able to take on such risks, the economy’s chances are poor. Innovation and entrepreneurship cannot survive without access to finance. Of course, in the aftermath of the 2008 global credit crisis we also understand what it means to be complacent about risk. We understand that the financial system must always walk the tightrope between excess exuberance and excess caution.

Few people, I think, would disagree that in Georgia today the signs of economic renewal are visible and the atmosphere of change is palpable. But what can we say about the “financial mood” in the country today? The numbers, unfortunately, do not tell an optimistic story.

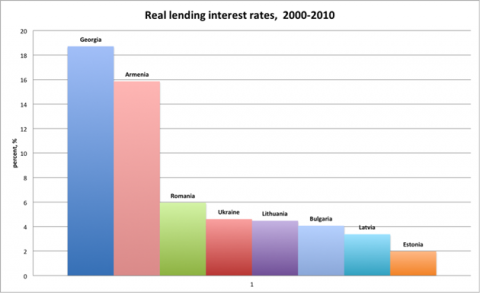

The real lending interest rates are some of the highest among the East European and Central Asian developing countries. Such high lending rates imply lack of borrowing and low investment.

In part, high interest rates could be explained by low levels of domestic savings (the issue discussed in my previous post “The Georgian Consumption Puzzle”). After all, if banks are short on deposits, they have to charge higher rates on borrowing, even if there are many viable and profitable business projects around.

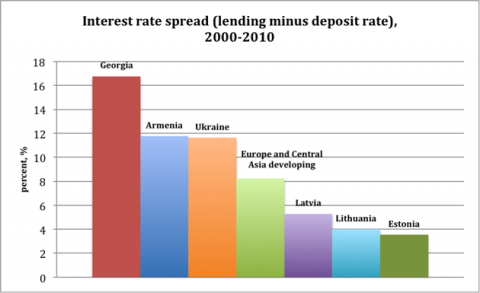

Although, if domestic savings were the main constraint, we would expect to also see high interest rates on deposits – the result of competition among banks to attract loanable funds. The competition for deposits would be evidenced in low interest rate spreads (the difference between lending and deposit rates).

However, as the chart below shows, this is not the case in Georgia. The interest rate spreads are quite high (almost twice as high as the average in the developing Europe and Central Asia).

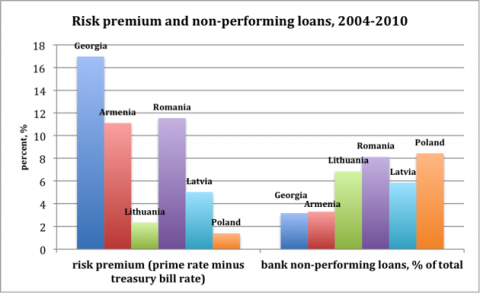

What can account for such patterns? The most likely explanation is the banks’ perception of credit risk. If we measure risk in the standard way, as the difference between the prime lending rate (the rate banks charge their best customers) and the “risk-free” government bonds rate, then banks in Georgia are quite pessimistic about the credit risk profile of private borrowers.

Additional indirect evidence on the credit risk perception and borrowing constraint can be found in the International Finance Corporation (IFC) Enterprise Survey for Georgia, 2008. According to the Survey, small firms (5-19 employees) are required to provide collateral to secure a business loan in 93.3% of cases (In Eastern Europe and Central Asia this figure is 77.4%). The value of the collateral needed to secure the loan is 237.3% of the loan amount (as compared to the average of 135.2 for similar size firms in EECA countries). Small businesses in Georgia also identify access to finance as a major constraint in 43.7% of the cases (as compared to 25.3% average for EECA countries).

What is responsible for such apparent excess of caution on the part of Georgian banks? For now I would like to leave this question open to discussion and comments. Let me just make an observation that rational optimism which would allow banks to “gamble on the future” of their country requires something more than just patriotism. First and foremost, it requires sound institutional frameworks to serve as the foundation for the belief that the bet on this future will pay off. Such institutions would allow the country to realize fully the potential and the promise of the years we are living through – the best years of our lives.

Comments

Brazil is another outlier, but probably for different reasons , see http://www.economist.com/node/21553077.

The figures you are reporting are averages for multiple years? Seems like an interesting puzzle to crack... Have to think some more (утро вечера мудренее)

Three thoughts:

1) The real lending interest rates are among the highest in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. From that I would infer that Georgia's country risk perception is very high - perhaps for political reasons, and local savings are very low (both affect the cost of borrowing for banks).

2) The interest rate spread is also very high. From that I would infer that most Georgian "projects" are of high-risk-high-return type. Returns are sufficiently high for firms to actually borrow (this is consistent with the observed very high level of markups). Risks are perceived as very high by the banks and hence lending interest rates and collateral requirements are very high. Interestingly enough, however, project risks have not materialized in Georgia. The percent of bad loans has been very low (so far).

3) In addition, collateral requirements are high because "collateralized" assets are relatively illiquid in a small market.

Would be interesting to get comments from the bankers in our community!

I also wonder about the calculations. What is puzzling me is interest rate spread being at around 16.5% while lending rate being 18.5%. Does this mean that deposit rate is 2%, or am I misinterpreting something? This, I think, is way off the reality. Another issue is are these rates for lending/depositing in GEL or in USD?

Zak, the lending interest rate is the real rate, while the interest rate spread from WDI I am pretty sure is calculated based on nominal rates. Assuming expected inflation rate is around 7%, the nominal lending rate would be about 25% while the deposit rate 9%.