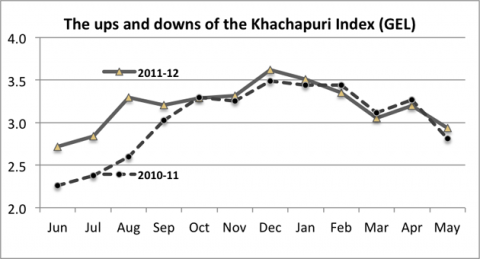

This week marks the first anniversary of the “ISET Khachapuri Index” in The Financial. During the last 12 months, our faithful readers have followed the ups and the downs of the index, and learned many economics lessons in the process.

The sharp seasonal fluctuations of the Khachapuri Index are very much reflective of the state of Georgian agriculture: fragmented, unorganized and underdeveloped. The roller coaster of agricultural production is no great fun for consumers and small Georgian farmers alike. When bringing their products to the bazari in high season, farmers receive only a fraction of the price they would have received had they used greenhouses or cold storage facilities to extend the season. Yet, small farmers are too small and too poor to buy fodder and fertilizer, let alone build greenhouses. With each Georgian farmer minding his own (very small) business, the sector has essentially become a refuge for the un- or underemployed. It is certainly not able to compete internationally, both with the Turkish imports to Georgia and in the lucrative export markets.

One common way to overcome fragmentation in agricultural production is to promote farmer organizations that could undertake joint investment in machinery and equipment, procurement of inputs (seed, fertilizer, etc.), processing, branding and marketing. Yet, successful farmer organizations are almost nowhere to be seen in Georgia. Sure, cooperation requires a common vision, mutual trust and … excellent management skills. All of these can only be developed over time. Yet, an argument is sometimes made that Georgian village communities are inherently individualistic, a tendency only made worse by the history of forced Soviet collectivization. True?

THE CASE OF SHROSHA

Anybody driving from Rikoti tunnel down to Kutaisi will not fail to notice the large ceramics market next to the Shrosha village. The market, known among the locals as “Bogiri” (an old word for “bridge” in the Imeretian dialect), has been in operation during the last 70 years, ever since the construction of the East-West highway. Jointly operated by 60 Shrosha village families, Bogiri provides an interesting example of Georgian-style community-level cooperation, with all its cons and pros.

Of a total of 400 Shrosha households, about 120 are in the ceramics business. Some of them have a stake in Bogiri, others sell their products to Bogiri resellers, as well as other roadside markets, restaurants and souvenir shops in Georgia. The land occupied by the Bogiri market is formally owned by the Zestaponi municipality, yet the elders of Bogiri perceive and manage the market as a joint enterprise. Since physical location in the market is critical to sales (higher in the center, lower at the edges), a key collective arrangement concerns the assignment of locations (small rectangulars on which clay products are displayed). Fairness is ensured through a weekly lottery, using real lotto game pieces numbered from 1 to 60! Accordingly, once a week each family is obliged to move with its entire merchandise. Inefficient, but fair.

The elders of Bogiri have been successful in designing and implementing many other collaborative arrangements as well. For instance, the 60 families abide by the agreed upon rules on how to display their merchandise (smaller items in front, larger in the back). Rotation is used to provide security services: one family stays on a night shift – selling own products and watching the rest. The 60 families are also quick to take collective action to lobby the local authorities. For instance, very recently they managed to block an attempt by one Shrosha family to break away from the pack and set up shop next to a water spring 100m away from Bogiri.

Surprisingly or not, the Shroshans are relatively lax on intellectual property rights and pricing. New non-traditional designs are immediately copied. Despite meek attempts to coordinate prices (by resellers facing higher costs), each family is free to set its own prices, and travelers can therefore engage in bargaining.

Yet, while providing a model of sustainable village-level cooperation, Bogiri is abound with examples of collective action failures. For instance, the villagers could never agree on a joint investment in infrastructure or in the common brand. Imagine the travelers’ shopping experience in the presence of an improved parking lot, a restaurant or café (think of wine tasting from traditional Georgian earthenware as a sales boosting tactic), yet none exist on site. Mind it that the 60 families would not oppose a private investment in a café (on which they could take a free ride), yet they cannot agree on a “joint venture” serving a common objective. Furthermore, until recently there was not even a road sign (!) inviting travelers to stop and shop for authentic Georgian pottery. The 60 families could not agree to jointly produce such a sign during their 70 year history of cooperation, including 20 years under a free market economy regime. The sign has been finally erected by the local Zestaponi authorities, perhaps as a result of successful collective lobbying by the Shrosha community.

The Shrosha experience suggests that the Georgian villagers are able to organize themselves when it is in their interest to do so. Yet, just like in the rest of rural Georgia, Shrosha’s version of bottom-up community organization has to be taken to the next level if it is to serve as an engine of modernization: facilitate investment in know-how and technology, and raise productivity beyond a mere subsistence level.

Comments

I agree that the subsidizes of government to agriculture sector and providing machinery and equipment can flesh out this sector. But, I think that the main problem in the Caucasus is the unwillingness of peasants to innovations. I observe that the peasant do not want to change their old habits. For example, the tomato grow up in the mid July in Azerbaijan. During this time, all the tomato products begin selling in the market. At a result, the supply of tomato exceeds the demand and it falls down the price of tomato and in turn it decreases the revenue of peasants in substantially level.Instead of this, they can cultivate tomato in one month earlier and can sell their products in the market in higher prices. maybe you can ask that the one month earlier cultivation can damage the tomato plants, no i surely know that it does not make any damages to the tomato plants.but when I said to peasant that you can increase your profit by cultivating tomato in one month earlier. The peasant reply that you are right,but we have been cultivate this plant in this time in every year since old times and it is our habit even the prices is cheaper. They are afraid to change their cultivation schedule and unwillingness to use innovations.Therefore, i think that firstly the economist should try to eliminate the old habits of peasants and solve the psychological reasons. If these problems are not solved,subsidizes in this sector and providing equipment and machinery will not succeed.I think that the peasant should spread out the time interval of cultivation of agriculture products. The main reason is the overproduction of one product in a certain time period.

Moreover, i also agree that the farmer organizations does not exist in the Caucasus. At a result, the monopolist artificially decreases the prices of products in overproduction period. I think government should help to peasants to create farmer organizations. I claimed that it is more essential than subsidizes or equipment in agricultural sector.

Indeed, resistance to change is a big part of the problem. Learning and adoption of new "technology" (including adopting a new timetable or seed, or a new crop) can happen through collaboration as well. Neighbours can learn from each other, just like is happening in Shrosha with new ceramics designs. Joint innovation can be perceived as less risky. Finally, there is the herd instinct. If everybody starts sowing earlier, maybe that's the right way of doing things. The problem is that, to be effective, collaboration has be very well managed. This is a serious bottleneck. The government could try addressing it but I would not want to concrete how-to suggestions

Dear Eric

Thanks a lot for this wonderful article (as all Kahathcpuri index analysis's always are!)

I full agree with every single word in the initial short analysis and in the final comments. Just one small comment: it is true that it is hard to find successful experience of profit oriented small farmers cooperation in Georgia…still, there are some., mainly supported by donors (SIDA/GRM, Mercy Corps, etc) , and some of them have proven to be very successful wand continue benefiting the members well after the external support. I was myself yesterday in Marneuli meeting a potato coop established with support of ACH. The support finished 3 years ago and the 30 people group is still working well and getting nice profit out of the gained economies of scale. FAO study on this matter looked into various dozens coops checking which one failed, and why, and which ones are making good.

Although few, this existing successful experiences have to be taken into account careful (and the failure cases) in upscaling the model

Juan

Many thanks for your compliments and the comment, Juan! I am hearing about successes in an number of geographic areas and agricultural sectors. Would be great to go around, document and analyze these successes. I am sure there would be a lot of lessons learned. It would be as important to learn from the failures... Is anybody already doing it?

At Tokyo Tsukiji Fish Market, the world's largest fish wholesale market in the worldm has a similar system of allocating spots to each wholesaler. Every 5-6 year or so, some 200 wholesalers draw lottery to choose a location not by auction or tradition. So they have to demolish the interiors and move to a new location and start over. It is interesting to note that Shrosa pottery sellers have the same system for equity. It shows that market needs not only price(greed) but rule .

Thanks for your support to our study.

I was just googling information on cooperation and came across to this wonderful illustrative example of "Georgian cooperation" and reality, and cannot stop myself to bring some modest comments of mine, since the cooperation issue in Georgian society puzzles me as well.

This article opens a venue to many interesting questions, which I consider to be important, but not addressed properly, without willingness to get to the bottom of deep roots of these problems. Get to the "microlevel". Why Shrosha rural community managed to cooperate in one case (arrangement, redistribution and security of the place) and fail in another ?(to erect the road sign, modernize the venue) Is it bacause in first case the self-interest matches with public interest and in another we have just public good (the road sign) Is it a Georgian (or transition) society specific phenomena or it is standard behavior what can we observe in Western societies ?( like free raiding on public good, selfishness vs. fairness,) Why successful cases of cooperation is so rare in Georgia, particularly in rural areas? Does the "bad experience" of Soviet regime partly responsible for that? Particularly, when we move in rural areas where the impact of "kolkhoz" type of cooperation was most salient and it's footprints are best observable until now. What is the heritage of the past? thievery, mistrust, state dependence, lack of individualism and absence of private property. Can such community produce cooperation and under what environment and condition? Are they capable of collective organization of production and merchandise?

The foundation of Georgian society has been always secured by countryside , "village" and the rural community that received the most of the blows of Soviet and post soviet era. Now it needs to be re-birthed within a new environment.

Thanks for an interesting article again.

Rati

P.S.

Neighborhoods

Outside the iron doors of neat and tidy apartments are untidy doorways and damaged roofs. Why they find it difficult to solve problems jointly (and its not solely because of finances)

NGOs

According to CIVICUS Civil Society Index 2010, the weakest link of NGOs is small social base. One third of the organizations do not have any volunteers at all. All of them are donor funded.

Education

One can look to the example of the self-governance of secondary schools, namely by boards of trustees established as a significant step toward decentralization and improvement of the educational system. However, the passivity of board members – parents – has rendered these boards largely ineffective.

and here some explanations on why Shrosha community did not erected a road sign and did not open a cafe.

road sign: One alternative explanation could be that its due to strategic consideration. It might be perceived by the villagers that positioning a sign in certain place, might give extra advantage to ones that are close to that sign and thus the sign could not be distributed and utilized equally by whole community.

cafe: Its related to the equality as well. Community might perceive opening of cafe as a threat to equal market opportunity. It's about a trust and belief. They might have belief that as soon as cafe would be opened, certain members would take strategic advantage of it.

As it seems, all their success in cooperation and collective action is based on equality and fairness regarding the market opportunities only - the place they market (but not prices and property right which is interesting observation). Same market place conditions for everybody!

Thanks for your comments and hypotheses, Rati! My explanation is different. I think the main difficulty of the community is in undertaking joint actions that involve the use of money. They have not undertaken a single joint investment!!! The road sign would not create any strategic issues since the market is very compact and everybody would be benefit in EXACTLY the same way. The same is true about the cafe. There in fact a small (lousy) cafe on site, but it is operated as a private business that does not try to cater to the needs of the community by marketing its products, etc. It is also so small and bad quality does nobody would stop at Shrosha for the sake of having coffee there...

I see now, of course if the site is so compact than the issue of strategic advantage is not relevant. That's interesting about the role of money; one experimental study shows that the reminder of money elicit more selfish behaviour and less pro-social behaviour (http://www.carlsonschool.umn.edu/assets/101518.pdf). The fact that the Shrosha community could not manage for 90 years to erect that bloody road sign is quite puzzling. One does not need an university degree to realize that the road sign would help to attract a visitors. May be the simply are very selfish, the road sign is perceived as "100%" public good to which nobody wants to contribute, while in other cases where Shrosha community managed to cooperate is less salient as public good and in those cases selfish motives overtake perception.

This gentleman from Zugdidi says Shrosha people do it the old way. He says his ceramics are the best in the country, they have enough clients, and have no need for advertizing or outside investors. Yet he laments that not many people are willing to spend 6 months learning his craft

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=DzD2MOwG3-k