Large gaps exist between male and female wages across the world. Eurostat data about the unadjusted Gender Pay Gap (GPG) represent the difference between average gross hourly earnings of male and female paid employees as a percentage of average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees. In 2011, in the EU, women earned 16.2 percent less per hour compared to men. The difference varies from 2.3% for Slovenia till 27.3 % for Estonia. The Worldbank Development Report on Gender Equality analyzed data of sixty-four developing and developed countries around the world and found the earnings gap between males and females with the same characteristics to be within the range between 8% and 48% of average hourly females’ earnings. The gap was found to be more pronounced in low income countries.

The available Georgian data tell a similar story. According to the National Statistic Office - in 2012 - for each 1 GEL of average nominal monthly salary earned by men women received 58 Tetri. Even taking into account the fact that women are usually working a lower number of hours than men, this huge wage gap in salaries is an indication to an existing gap in hourly wages too.

WHY DO WOMEN EARN LESS?

Why is there a gender pay gap? Many would be quick to answer: it is because of gender discrimination (and probably suggest tougher anti-discrimination legislation)!

This, however, is far from obvious. Even if, controlling for demographic characteristics (age, region (urban/rural), education, marital status, and presence of children) and job characteristics (hours of work per week, employment status, occupation, economic sector and formal/informal nature of the job) much of the earnings gaps remain unexplained, suggesting that the gap could be also due to other characteristics we are not yet taking into account. Among other causes that could explain the existence and the persistence of a gender pay gap particularly interesting are the differences in individual lifestyle preferences.

Preference theory, a multidisciplinary (mainly sociological) theory developed by British sociologist Catherine Hakim, postulates that women’s expressed preferences are better predictors of their employment status than their education levels. She argues that preference theory largely explains the persistence of sex differentials in labor markets and also the gender pay gap. Women would tend to favor quality of life and job satisfaction over higher earnings. In support of this theory, the economist Arnaud Chevalier from the University of London surveyed more than 10000 people in the UK and found than men are more likely to state that career development and financial rewards are very important, and to define themselves as very ambitious, while women emphasize job satisfaction, being valued by employers and doing a socially useful job. Two-thirds of women in this sample expect to take career breaks for family reasons; 40 per cent of men expect their partners to do this, but only 12 per cent expect to do it themselves.

LIFESTYLE PREFERENCES IN GEORGIA

Individual lifestyle preferences are likely to play an even greater role in Georgia due to our predefined attitude towards gender roles and their consequences. Georgia is a unique country, characterized by a distinct mix of western and eastern values. Women are raised in a patriarchal society, where gender roles are predefined and deeply engraved from the childhood. Most of Georgian girls grow up hearing the following statements: “you cannot stand alone”, “you are too fragile”, “you are in need of protection”, and so on. As a woman you feel that the main determinant of your personal success in this society is not having a successful career; rather it is your marital status and, more specifically, fulfilling your obligations as a woman, as a housewife, and as a mother.

THE “CINDERELLA SYNDROME”

These social factors increases the likelihood that Georgian women “develop” the so called Cinderella syndrome, related to Catherine Hakim’s theory explaining the gender pay gap. The Cinderella syndrome describes a women's fear of independence, and her unconscious desire to be taken care of by others (men). This alleged syndrome was first described by Colette Dowling in her 1981 book The Cinderella Complex: Women's Hidden Fear of Independence. This - mainly psychological - factor is usually not accounted for by economic analyses of the gender pay gap, although it probably should. In particular for analyzing wage differentials in traditional countries like Georgia, psychological factors might subconsciously affect women’s labor supply, their reservation wages, and even their performance at work (especially when competing with men), ultimately resulting in larger pay gaps.

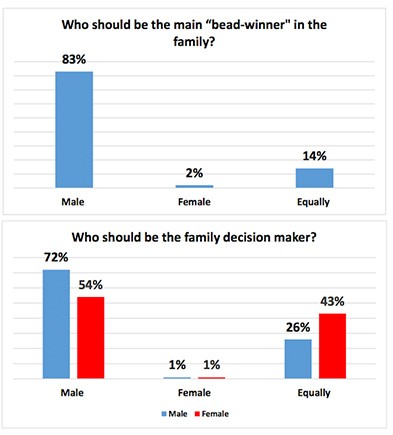

A survey on gender issues based on telephone interviews, carried out in Georgia in 2012 by the Center for Social Science, provides support for the possible existence of the Cinderella syndrome in Georgia. The survey shows that a large part of the interviewed believes that men should be the ones who are the family's decision-makers and that they should also be the main “bread-winners”. 83% of respondents think that men should be the main bread-winners in the family and 63% believe that they should also be the family’s decision makers. It is interesting to note that more than half (54%) of women agree that men should be family decision makers. In addition, 92% of respondents think that the most appropriate age for getting married for women is 18-25 years old. As 18-25 is the age in which individuals are acquiring human capital and skills for their future careers, it is not unreasonable to expect that, if this time period is used for child bearing and rearing, it can result in women possessing lower level of skill and consequently receiving lower earnings.

CONCLUSION

There is a gender pay gap between males and females in Georgia and it appears to be large. Discrimination might explain part of it but it is certainly not the only cause. Differences in attitudes, cultural background, and psychology, affecting lifestyle choices, are also likely to play a major role in this. Instead of using discrimination as a scapegoat on which to blame the existence of a gender pay gap and consider it as an evidence of a problem one should get rid of at all costs, it would probably be better to look at things in a more differentiated way. What if important factors for the current state are to be found in females’ own choices? What if individual and social preferences were driving what we observe in the labor market? Would the existence of a gender pay gap really constitute a problem then?

As long as there are no external effects involved and individuals are fully aware of the implications of the choices they make, the best course of action might be to let everyone decide what is best for her. Even continuing to look for the Prince Charming, if one feels so.

Comments

I think you should take a look at the way Western economists actually explain the wage gap. Contrary to what you have said here, almost all of them explicitly take individual preferences and lifestyle choices into account.

I would recommend you start with this link: http://www.policymic.com/articles/33469/equal-pay-day-this-is-why-women-still-make-less-than-men

or this one: http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2013/04/09/1839281/on-equal-pay-day-why-women-are-paid-less-than-men/?mobile=nc

Also, Georgia is no different from the US or other countries when it comes to gender roles or ingrained (not engraved) attitudes about a woman's place - except that in the US we've been fighting back against those attitudes for a little bit longer.

Finally, I note that you say that the Cindarella complex is subconscious - but if women are making their choices based on subconscious fears and desires, then by definition they are not fully aware of the implications of the choices they make. By choosing to stay out of male-dominated fields and to allow men to make the money and the decisions, they are perpetuating the stereotypes that cause the Cindarella complex, in their own families and in society as a whole. In other words, the personal is political.

You point out that women in Georgia (although this is true elsewhere, too) are told from a young age that they are dependent, fragile, and in need of protection, and that they develop fear and dependency as a result. Do you really see no problem with women being paid less money because they have been frightened into submission by their family and their society? Does that not count as an "external factor" in your economic analysis?

The main (and only) point of the article is that the gender pay gap is not caused by discrimination but rather by the difference in preferences. It is rather unfortunate that the last sentence makes a value judgment that is at odds with the main thrust of the piece.

Now, I agree that we have to worry about preferences, norms and values being “unconsciously enforced within a society”. But I would be equally concerned about consciously enforcing a change in values, tastes and preferences, especially in cases that do not involve significant externalities.

My favorite example concerning the latter is the futile attempt by a radical left-wing Israeli kibbutz movement to force complete gender equality by “freeing” women from the need to do laundry and dishes, cook, breastfeed and take care of their children. For those who are not aware of this interesting experiment in gender equality, here is a bit more detail. Kibbutz houses had no kitchen (it took a long time to allow small refrigerators and kettles) and children were put 24/7 in a “baby house” almost at birth. To repeat, babies and children did not live with their parents. Mothers and fathers would typically visit and play with their kids after work, implying perfect gender equality as far parenthood is concerned. Food, clothes were centrally provided. All men and women worked in roughly the same jobs in the best of socialist traditions.

Importantly, the larger society was also quite keen on gender equality. For example, consider that IDF is (still) the only army in the world where men and women are obliged to serve.

Ok, there have been other aspects of socialization beyond the kibbutz control (movies, books, role models), but this experiment in “consciously enforcing a change in values, tastes and preferences” was as radical as one can imagine.

In the 60s and 70s, this rigid system started unraveling as it was deeply unnatural and fundamentally flawed. By now it is history. Why forcefully make men out of women and deny them the right to exercise Motherhood?

I too would be concerned if women were forcefully subjected to a radical experiment in communism conducted by small Israeli farming communities that failed fifty years ago never to be replicated. However, I think there is probably some middle ground between society telling women they are too fragile to work and society taking babies away from their mothers to be raised in a communal genderless day care center.

Is that really the way you see the people on the other side of this argument? Do you honestly think that those who argue that women should receive equal pay for equal work are ultimately trying to turn women into men? Do you think that people who argue that teachers and nurses - and mothers - should be compensated more for their work are actually just biding their time until they can destroy the institution of Motherhood once and for all?

As long as you're painting these ridiculous pictures of the other side, you are failing to engage in constructive dialogue, which is why both the original article and your comment clearly demonstrate that neither of you have engaged with or understood the modern discussion about the gender gap in wages. If you want to understand what a modern capitalist society that addresses the wage gap looks like, maybe you should look at how other modern capitalist societies have actually addressed the wage gap, rather than focusing on strategies for small, intentional agrarian communes.

Neal, that's not how I see people on the other side of the argument. I am not even sure what is the "other side" and which side I am on.

I don't think your comment on my comment or on the article is fair. There is nothing in the article or in my comment to suggest that it is ok for women to get less (per hour) for the same work. Do you really think the author or I am in favor of blatant discrimination? Please...

I drew a ridiculous picture of a community trying to eliminate gender differences because I don't believe in forceful elimination of gender differences.

First, gender difference exist, they are grounded in biology, physiology and evolution theory. When looked from the evolutionary perspective, women are much more necessary for the survival of the human species than men. It takes only two-three healthy males to reproduce a nation. This is probably why women are much more risk averse (as confirmed by experimental evidence). Risk taking is a male attribute. Men are therefore more likely to fight, start new businesses, and discover new lands/planets.

Second, while the problem of socialization into submission is real, violent rhetoric and institutional solutions a la the Israel kibbutz experiment are likely to backfire. The problem has the all the attributes of a systemic nature, and like any systemic problem it cannot be resolved from within the system. You need either an external impetus (a nuclear catastrophe killing all the males, such a humorously described in the Polish classic "Sexmission" http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0088083/) or ... patience. Yes, patience.

Time is working in women's favor. Technological changes have already transformed the human workplace as brute force is no longer required for most tasks. Instead what is more needed in manual occupations is fine motor skills in which women may have an advantage). Technology also changed human houses and kitchens (an argument is sometimes made that the washing machine had a more profound impact on humans than the internet). Finally, we now have many more female role models - Margaret Thatcher, J. K. Rowling, Meg Whitman, the top 100 female CEOs, etc., etc. A few countries now have female majorities in parliaments and governments. In fact, ISET is held together by women who pretty much run the show even though I carry the director title

See, the problem is that the article actually does suggest that it is okay for women to receive lower hourly pay for the same work.

The author goes out of her way to point out that the wage gap remains unexplained even if you take into account the fact that women work fewer hours - all the way up in the second paragraph - and then in the fourth paragraph goes on to acknowledge that the wage gap persists even when controlling for demographic and job characteristics. What that means is that women who share demographic characteristics with men, have similar educational backgrounds, and work similar jobs for similar numbers of hours are still paid less money for that work.

And that's the starting point of this article - the thing the article claims to explain by resorting to preference theory and that the concluding paragraph says would be justified provided that women aren't hurting anyone and go into it with their eyes open.

The author then brings up psychological factors, in particular mentioning women's reservation wages and competitiveness, as one possible explanation for the wage gap. I agree with that. As it says in the blog posts I pointed to, there clearly is a set of behaviors that results in women getting paid less than men. For instance, women are far less likely to negotiate their first salaries than men, and a person's salary history impacts their future salary negotiations, and so this can have a ripple effect that results, twenty years later, in a man being paid much more than a woman for doing the same work. This is probably not a result of discrimination by any particular company, but it does result in women being paid less money for working the exact same number of hours at the exact same job.

But let me be completely clear, because I don't think you understood this part: when we talk about these psychological factors impacting competitiveness and reservation wages, we are absolutely talking about women making less money for doing the same work. We're saying women get paid less because they don't demand as much as men demand because they don't value their own labor as much as men do and because they are not concerned about being the primary income earners in their families.

So this is exactly what the article is saying is okay: women getting paid less, per hour, for the same work, because women behave differently than men. Not because they work differently, but because they demand less compensation for that work because they have been told to.

Neal, I appreciate the change of tone, from disrespectful ("you have not done your homework") to combative to somewhat more balanced. The issue of preferences is complicated and neither you or I are qualified to judge which is right. Maybe it is the overly ambitious men - the CEOs among us - who should change their preferences and instead of putting in 16 hours a day (which may explain a part of the wage gap, by the way) stick to working 8 hours, 9-to-5, go home, forget about work for the rest of the evening and try to spend more time in meaningful communication with children. Maybe be instead of preaching women to become men we should start preaching men to become a little more like women. Think less of careers and money, and more about family and personal development. That would bring down the wage gap and make everybody better off.

I am not an expert in the field but here is an interesting question (I'm sure many have already though about this): why people talk about female and not about male, in this context? If one says that this is a silly question because its obvious that female earn less than male, male will is often imposed over female etc. then there is something wrong, call it discrimination or imposition of preferences, that works only in one direction. The thing that works only in one direction reveals that male are more "powerful" than female due to natural, historical or whatsoever reasons. Because men are more "powerful" then they can use the power either directly (coercively) or indirectly i.e. by affecting female preferences. The thing is that male can and do use the power. I think one should not deal with the "can" part because it would be unethical from a normative point of view and would reverse the problem, from a positive point of view. Then, one should deal with the "do" part. Good anti-discriminative laws (curbing any type of direct display of power of male over female) and education (empowering female, making male tolerant and dealing with all the preference imposition problems) should be sufficient for that. Those tools are being used by modern capitalist societies to address discrimination issues be it on the basis of gender, race etc.

As Eric pointed out, I believe there is some misunderstanding about the true point of the blog post.

The purpose of the blog (which is obviously not an academic paper - like the links suggested by Neal) was to discuss whether or not it could be conceivable that - in the Georgian context - attitudes and social norms might explain part of the gender wage gap.

The final conclusion might sound provocative, and it is supposed to be (without affecting the validity of what was written above).

It should, however, be read carefully. In particular, the main points are: 1) if there are no negative external effects generated by the fact that both man and woman inside the household "prefer" women having a different role in the household; 2) as long as individuals are fully aware [this is not speaking of an inconscious decision] of the implications of the choices they make, in terms of future potential earnings and career opportunities; 3) the best course of action might be to let everyone decide what is best for her. These are obviously very strong assumptions.

Obviously one might find that 1) is not true, or that 2) is not realistic (if one thinks choices are made ignoring available information). Obviously, in that case, 3 would not be true.

However, for the sake of the argument, if the gender wage gap was determined solely by a fully conscious choice, given personal/household preferences, what right would have a society to "impose" equality?

We are not proposing how to deal with the gender wage gap here, not even saying whether it is good or bad that the gender gap exists, just to contribute to the discussion and to help people think and distinguish what is a legitimate concern (discrimination in the labor market and/or in the society) from what is not (individual preferences).

Actually the links I suggested are also blog posts, not academic papers. The purpose of the links was to point out that not only is it conceivable that attitudes and social norms might explain part of the wage gap - it is, in fact, generally agreed-upon and well-known.

The fact that the authors of this piece failed to include current scholarship on the topic and instead proceeded as though they were taking a novel and unexpected approach struck me as suboptimal and I hoped that by commenting I could encourage the authors and readers towards additional lines of research, thought, and inquiry.

I do not believe that I have misunderstood the post at all. I did not dispute that the conclusion that you have elaborated upon was incorrect. Instead, I provided examples of why your points 1) and 2) are not satisfied by the current social arrangement - examples which you have not addressed in your comment.

However, since you mention it, I now also wish to dispute the logical premise of your conclusion as well as the facts of the matter. Let's assume the gender wage gap can be entirely attributed to women's fully-informed choices - that if women behaved exactly as men did, women would make exactly what men did, but women are different from men and so women choose differently than men and so women make less money from men.

Why is it that male choices are more valued by society than female choices? Put another way, if the money you receive for making a certain choice is considered an incentive to make that choice, then the economic system that you are defending incentivizes women to behave exactly like men. If we want women to pursue traditional female work - like being mothers, teachers, and nurses - then shouldn't we pay women more to do those jobs?

American society is a great example of what happens when women who have the ability to work and who have legal protection against discrimination in education and employment are given the real option to choose between family and lifelong earning potential: they begin to choose earning, in ever-increasing numbers, and the rate of population growth slows accordingly as women have children at a much older age, or not at all. If you want your society to grow and thrive, the sensible thing to do would be to pay women a fair wage to raise their children - then women wouldn't have to choose between motherhood and economic security.

Instead, we live in a society that rewards the choices men make and penalizes the choices women make. That is social discrimination, and it perpetuates the problems this article mentions: the fact that women are taught to be fearful and dependent on men. Blaming gender roles for discrimination is putting the cart before the horse - the discrimination creates fearful and dependent women, not the other way around.

Neal, I appreciate the passion you are putting in this discussion and your suggestions. I would like to reassure you that we are well aware of the fact that a lot of research has been done about the gender wage gap, including research about the importance of individual preferences and attitudes. As a matter of fact our purpose was not to write a review of the literature but just to discuss one specific factor that might have a certain relevance here in the Caucasus.

Moreover, we wanted to stress the fact that there might be a part of the gender gap one would not need (nor want) to eliminate. Obviously you are free to disagree.

This said, you have NOT proven that assumption 1 and 2 are ALWAYS wrong. You have simply pointed out that they might be, and if they are, one should do something about it, something that is in perfect agreement with what is written in the blog post.

Concerning the rest, I believe your question (and objection) "Why is it that male choices are more valued by society than female choices?" is totally misplaced, as are your conclusions (given the "setting" proposed).

The gender wage gap we would observe in a world with no discrimination but just differences in preferences would simply be the consequence of the free choices of women.

In this sense, if women decided to work less extra time to spend more time with children (for example), or cooking a nice meal or to do gardening or shopping(to make a few silly examples), knowing well that this would lead to a lower salary, their (non-monetary) compensation for their lower wage would exactly come frome that. [The same would be true for men doing the same choices.] Forcing wages to be equal (or compensating women for these choices) would, in fact, be a discrimination against men [or women doing different choices].

The point of the blog post is not what WE want men and women to do, it is what THEY want to do.

"Our" concern(once real discrimination is eliminated and externalities are taken into account)should only be to make sure people take into account fully the consequence of their actions when they decide what to do .

ONLY IF you assume (maybe rightly) a divergence between what would be desirable for society, and for the individuals (therefore assuming the presence of external effects - as mentioned in the post), a rationale for intervention would exist.

Finally, our purpose is not "blaming gender roles for discrimination" but discussing one potential explanation of the gender wage gap that differ from discrimination. This does not deny that social discrimination exists nor that it can create fearful and dependent women.

On the other hand, you seem to imply that having successful and strong women choosing to earn less than men after thinking rationally about it is impossible and/or unrealistic. On this I have to disagree.

Fascinating and encouraging to watch the back and forth between two men on this issue.

"

"

Yet still, I wonder why the male director of ISET is not stepping back and allowing the female author of the blog post to defend her work herself?

...maybe she doesn't get paid enough.

But here's the worst:

"In fact, ISET is held together by women who pretty much run the show even though I carry the director title

Well isn't that perfect! Not only are you getting the lesser-paid, yet over-qualified women that work for you to "run the show," but you've also managed to have them internalize their inferiority by writing the above blog post. (I.e. It's our own fault that women don't get equal pay for equal work! We just don't make the right choices!)

No wonder you followed up that comment with a smiley face -- you've managed to secure a pretty sweet job (and title!) for yourself while admittedly exploiting the women around you.

Dear Neal, thank you for your comments. I really appreciate that you have spent so much time on this blog post. Norberto and Eric have already replied to your comments, but I would like to stress one thing again. We are aware of the literature on gender wage gaps, and discussions going on in the academic circles quite well. We just wanted to stress and discuss the idea of the Cinderella complex as one of the explanations (together with all others) of the existing gap, because this might be particularly interesting for Georgian context.

I have been reading the debates around this post and I find them very interesting and though-stimulating. Here are my 2 (female) cents into the bank of thoughts.

The other day I came across an interesting paper on the issue of gender wage gap (see http://www.nber.org/papers/w14681) that follows job careers of male and female MBA graduates from one of the top U.S. business schools (2+ thousand people followed for a decade+). It looks like both men and women start their career with almost identical labor income (so, at least from this study it does not seem that women negotiate worse their starting salary), but soon their earnings start diverging, with average male income being some 60-80 % above that of women after 10 years on the job market. Interestingly, most of this difference is explained by the fact that women have more career interruptions and work shorter hours, including more work in part-time positions and self-employment. The main reason for this career pattern is something that simply sucks (at least in the beginning) – a child. It appears that the careers of MBA mothers slow down substantially following their first birth. This slowdown is especially pronounced for women with well-off spouses. So, there seem to be some high-powered MBA Cinderellas living in the US and choosing not to go after more career/work/pay and giving more time to their families. Are they making the wrong choice? With the level of education and work opportunities they have, plus given highly modern norms they most likely grew up with, I will not doubt their choices. Should these women be compensated for the choice they are making (by the way, we are talking about hundreds of thousands of dollars in foregone earnings)? I don’t think so: I am sure MBA mothers are in a condition to carefully compare costs of their decisions with benefits, and the fact that they choose to become mothers means the net benefit is positive.

It is important to take into account all the costs and benefits of a decision, otherwise it is very easy to brand it suboptimal. Also, focusing only on individual costs and benefits of a decision might be equally misleading, especially in this case. After all men and women sometimes (and more often than not) come in pairs: they complement each other by forming FAMILIES and they work together as a team to achieve common goals. And if each person has a comparative advantage in something, what is wrong with exploring it to make the family better off?

P.S. By the way, guess what? According to the study, the income that women get after controlling for the “motherhood” effect is only 1-3% below that of a comparable men, so there is almost no difference in pay.

Very interesting paper, Karine, your two cents are much appreciated!

Kazbegi your comment is inappropriate and out of place. I think you have missed the main point of the blog post. I as a woman wanted to show possible existence of this problem in our society and tried to be as much objective as possible not to embarrass women suffering from Cinderella complex. Main goal was to give audience topic to think.

Dear all,

I received ISET's newsletter several days ago and saw your blog and the (engaging and, I would even say, passionate) discussion that followed. Because I, too, have been doing some work on the gender wage gap in Georgia, I couldn’t resist adding several thought on this.

My sense is that the Cinderella syndrome in Georgia is primarily manifested in the differences in the endowments (explained portion of the gap) rather than the differences in the returns (the unexplained portion of the gap). That is, a woman who exhibits a Cinderella syndrome is likely to reveal it in the choices (i.e. endowments) she makes with respect to job flexibility, industry, occupation, hours of work, when and whether to get married and have children or not, and so on, choices which are distinctly female and which explain why her wage is lower. So the norms/preferences are translated into different endowments and, via these endowments, into differences in the wages.

On the other hand, if a woman chooses to share the same characteristics as a man, this implies that she is less likely to have the Cinderella syndrome to begin with (think a female miner). Hence, although it might still play a role, the Cinderella syndrome is less likely to be the primary reason explaining the unexplained portion of the gap between the wages of equally qualified men and women (i.e. the differences in the returns).

With that said, I believe a major hurdle in properly explaining the gender wage gap in Georgia is our inability to do a decent job at controlling for relevant variables. For example, the authors in the paper that Karine cited controlled for the break from work due to childbirth and found very little unexplained portion of the gap. In contrast, the Georgian household survey data tells us almost nothing about the work history of individuals. If there are wider gender differences in work experience than can be proxied by age (which is likely to be the case), the explained portion of the gap is underestimated (and the unexplained portion, therefore, overestimated). I am not even addressing how little we know about less quantifiable but no less important factors, such as job flexibility and work environment.

Despite these data limitations, however, we can do more to deeper investigate the underlying reasons for the gap. For example, the role of employer discrimination can be illuminated by looking at the magnitude of the wage differential between self-employed and wage workers. The wage gap in Georgia appears to be wider for wage workers than for self-employed individuals (granted that the data quality of self-employed earnings can be quite poor), which seems to suggest that the employer discrimination might in fact be at play. To explore whether norms indeed play a role in determining whether women, who are otherwise identical to men, choose to receive lower wages (without making any normative judgments as to whether this is acceptable or not), one could look at different age cohorts. Presumably, younger generation is less likely to think so and so the heterogeneity in the results or lack thereof may shed light on this question.

This post got a bit longer than I had initially intended, but I am glad that we are starting to see a discussion of the gender wage gap in Georgia grounded in solid empirical work. So thank you for your blog and for initiating this conversation!

Tamar

Dear Tamar,

Thank you for your interesting and overwhelming comment. Hope this topic will gain more attention. You are right even with the limited data we can identify sources of the wage gaps in our society. It would be interesting for us if you could share your research results with us, if they are public of course.

Thank you very much in advance.