Consider yourself in Germany in 1923, entering a bar for drinking a beer. How much would you have had to pay for that? Well, the average price for a glass of beer in the autumn of 1923 was four billion Marks. One year before, you could have bought it for less than 300 Marks, and in the beginning of 1921 for about 30 Marks.

In 1923, a phenomenon called hyperinflation reached its peak in Germany. People who received their salaries in the morning had to have spent it by the evening, because on the next day it would have lost most of its value. The values of many banknotes were lower than wallpaper, and so it happened that money was used for papering apartments. Likewise, notes were also a convenient substitute for briquettes.

Inflation and deflation remind us of the fact that money has a price. Given that the prices of the commodities and services in an economy are stated in terms of money, this is something one can easily forget. Yet like the prices for butter, cars, and cigarettes, also the value of money is determined by supply and demand. Instead of having money prices, in principle prices could also be stated in terms of cigarettes, bottles of vodka, or kilos of wheat. Indeed, when there is so much inflation that people lose trust in their currency, it regularly happens that they resort to so-called commodity moneys, i.e. some handy commodity becomes a means of payment. Commodity money is not prone to inflation, because if your cigarette money loses too much value, you simply smoke it.

SUPPLY AND DEMAND

The National Bank of Georgia is the only institution that can legally print Laris, which are then injected into the economy through various channels. If they print too generously, however, people have more money in their pockets for buying goods and services, while the production capacity of the economy remains the same. If there are idle capacities in the economy, at first the increased demand will be met by an increase in output, but soon there will be a point where producers and service providers raise their prices. Inflation results.

There can be other reasons for inflation. Since the second half of 2012, Iran is struck by heavy inflation, leading to violent demonstrations and social unrest. The reason is not that the Iranian central bank had printed too much money. Rather, the Iranian inflation is caused by the additional international sanctions imposed against Iran in the summer of last year. These sanctions make it very difficult for the Iranian economy to export their produce, notably oil. Yet with Iranian Rial one can pay for those things produced in Iran, but for little else. If due to the sanctions, Iranian products cannot be bought anymore by foreigners, who outside Iran wants to have Rials? Consequently, the value of the Iranian Rial plummeted vis-a-vis the US Dollar, leading to soaring prices of all goods which contained imported parts.

THE PRICE OF INFLATION

Surprisingly, it is not so easy to explain why home-made inflation should be bad. If all numbers in an economy increase continuously, including all prices, all wages, rents, pensions, taxes etc., it should not have any effect on real economic activity that there is inflation. Of course, inflation creates incentives not to hold cash, but this will lead people to bring their cash to the bank, where they get interest, not creating economic problems. Indeed, since the beginning of economic thought, there were people who held the view that money is but a veil, something which does not have an impact on real economic activity.

Yet as a matter of fact, most people do not like inflation which exceeds a threshold of approximately 3%. One reason is that the adjustments of prices and wages do not proceed simultaneously. While most commodity prices can be adjusted at any time, labor contracts specify wages for some period of time. In Iran, people were going to the streets because their salaries were not increased, while prices for food, medicine, and other basic needs had gone up. Though their inflation was not home-made, the distress caused through inflation was not different than anywhere else.

Another problem is that in an inflationary environment, making commitments to deliver or buy goods at a pre-specified price gets riskier, in particular as the inflation rate typically is not constant. With a lower inclination to commit, economic planning gets more difficult, causing real harm to the economy.

Governments are always seduced to cover their expenditures through printing money. There is just no simpler way of financing a budget. This explains why inflation and even hyperinflation can be seen in the world very regularly, in particular in countries where the central bank lacks independence from the government. Also in 1923, Germany had a political interest to create inflation. Germany was forced to pay reparations to France and England for World War I, and the money for these reparations was simply created in the printing press. The resulting inflation was intended to demonstrate to the Western Allies that the war reparations exceeded Germany’s economic potential.

THE NIGHTMARE OF DEFLATION

What would you do if you expect your Laris to increase in value every year? Well, instead of bringing it to the bank, you might let your money stay idle, storing it in a mattress at home, or, less old-fashioned, keep it in a fully flexible current account at the bank. Only very high interest rates at the bank could induce you to let your money work in a savings account. However, the more money is lent to the banks for longer terms, the more money can be passed on to investments that stimulate economic activity. If the banks have to offer high interest rates for collecting such money, only the most profitable investments can be financed, leading to lower growth and reduced economic activity.

Since about 1990, Japan experiences a long phase of deflation. For Japanese people, prices get lower every year. This is a blessing for the consumers, but Japan as a whole suffers severely. Incentives to invest are low and consumption is postponed to next year, when things will be even cheaper. It seems easy to resolve deflation by letting the printing presses run hot, but despite several Japanese tries to overcome deflation, this did not work out. Once being in a deflationary cycle, where everybody expects prices to be lower next year, also additional money provided by the Bank of Japan did not help. Interest rates are already at 0% for many years, and negative interest rates come close to an economic impossibility.

AND GEORGIA?

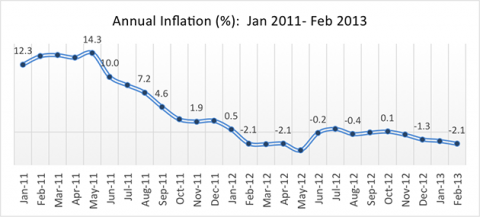

Since about one year, Georgia is on verge of deflation (see chart above). Will Japan’s experience repeat in Georgia? Chances are low. While in 2011, Japan had a nominal output of almost 6 trillions US$, Georgia produced just 14 billion US$. So Georgia’s economic performance accounts for less than 0.3% of Japan’s. This means that the domestic savings and consumption behavior is far less important for the Georgian economy than it is for Japan. Unlike Japan, Georgia first and foremost depends on foreign money for financing its investments. Also the domestic consumption in Georgia, a considerable part of which goes into imports, has limited potential to stimulate the Georgian economy. Being much more dependent on foreign money than Japan, the deflationary tendencies may turn out positively for Georgia, because they make the Lari an attractive currency for saving value, and they cause a projectable and stable environment for foreign investment.

Comments

I used to be able to smoke my money back in 1986! I lived in Romania (as a young Israeli diplomat) and the going currency for most intents and purposes at the time was Kent cigarettes. It was not just any Kent, but the long version! The reason the Romanian people used Kent cigarettes as money was this. Holding and/or using USD or any other foreign currency was a punishable crime under the Romanian legislation at the time. Kent was an excellent "legal" equivalent to hard currency as opposed to Romanian paper money. It could be used as store of value and - very importantly at the time - to gain access to high quality local or imported goods which were only available to "speculants", diplomats and foreign tourists.

I could pay with Kent for groceries, taxi, and most other daily expenses. Given that I could import Kent cigarettes tax-free through special companies catering to diplomats, I was getting a really great deal! For instance, a skiing weekend in Poiana Brasov (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poiana_Bra%C8%99ovPujana) for a couple, including hotel, three meals, equipment rental and lift cost as little as 10 Kent packs. I remember importing huge quantities of cigarettes, only a small portion of which I actually ended up smoking. But, yes, I did smoke some of my money.

Very interesting -- I did not know you experienced Ceaucescu's Romania from the inside! Somebody who visited Romania in the 80's told me that condoms were another popular commodity money. Ceaucescu wanted to brutally increase its population by prohibiting any contraceptives whatsoever. Women were not allowed to abort pregnancies, and bi-yearly forced gynecological examinations aimed to register any pregnancy and prevent illegal abortions. As a result, a condom was an extremely scarce commodity, traded at astronomical prices. When this guy entered Romania in the 80's as a tourist, he could cover most of his expenses with the package of condoms he had brought with him. Would be interesting to know how many Kent cigarettes traded for one condom.

I fail to see, why Georgia's economy being much smaller than Japan's can be translated to statement that domestic savings and consumption are not that important. I kinda agree with whatever follows, but not with that part.

Hi Giorgi, Probably you agree that Georgia can finance its rapid growth only by attracting foreign money. The Japanese economy, on the other hand, depends crucially on domestic investors, who traditionally have a strong inclination to invest in Japanese companies. Likewise, the Japanese government is known to finance its abysmal budget deficit almost exclusively through Japanese lenders. So by and large, Japan does not depend on foreign money as much as Georgia -- for foreign investors however, the Georgian zero-inflation environment may be quite attractive, and so it looks to me as if the deflation problem isn't that severe for Georgia.

True. But that's a different argument whatsoever. Size of the economy doesn't come into it.

Another comment. "Commodity money is not prone to inflation" - of course it is. More money with the same amount of stuff to buy = inflation, whatever is used as money.

Sure, but if commodity money gets too cheap, people start consuming it. Everybody smoking cigarettes = prices for cigarettes go up. So there is an automatic stabilizer for the price of a commodity money.

Ok, all of a sudden you have ten million cigarettes - do you consume them all? And I'm not talking about conventional commodity money - like gold, silver or cowrie shells.