While more than half of all jobs in Georgia are in the agricultural sector, agriculture’s share of value added to GDP was only 11 percent in 2007 (World Bank). And although Georgia was a major producer of food, wine, tea, and mineral water during Soviet times, most of the food products on the shelves today are imported from abroad (FAO).

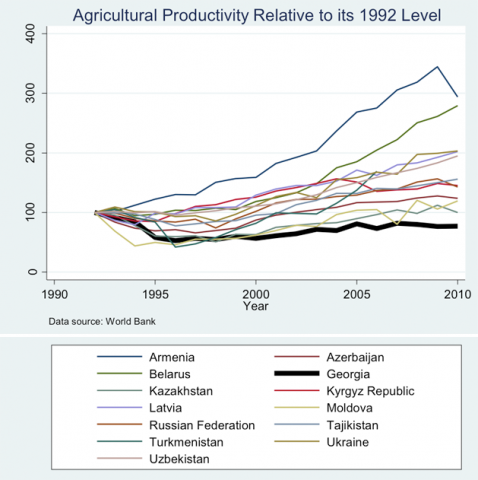

Yet what is even more remarkable is that Georgia seems to be the only former Soviet republic in which agricultural productivity hasn’t returned to or exceeded its level in 1992. As of 2010, agricultural productivity stood at only 77 percent of where it was at nearly two decades ago.

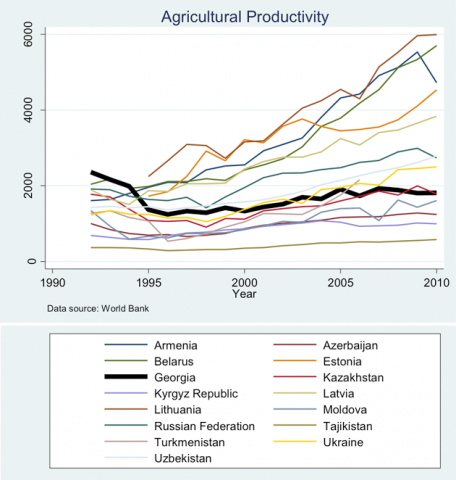

The graphs below illustrate the puzzle of agricultural productivity in Georgia. The first graph is of agriculture value added per agricultural worker in constant 2000 US dollars (the data come from the World Bank). The second graph is of agricultural productivity relative to its level in 1992, multiplied by 100. If this index equals 100, for instance, this means agricultural productivity during a particular year was exactly the same as it was in 1992. If the index equals 200, this means agricultural productivity has doubled since 1992, and so on.

Note that Estonia and Lithuania are absent from the second graph due to missing data from 1992 to 1994. Nevertheless, it is clear from the figures in the first graph that Estonia and Lithuania have experienced tremendous growth in agricultural productivity over the past two decades.

While agricultural productivity is currently much lower in Tajikistan or the Kyrgyz Republic, Georgia appears to stand alone in terms of never recovering to its previous level of agricultural productivity.

So, the question remains: why hasn’t agricultural productivity improved in Georgia over the past two decades, while it has at least recovered in every other former Soviet republic? It is even more puzzling to consider why agricultural productivity has grown by nearly 200 percent in Armenia since 1992, while it has declined in Georgia since then. These are certainly interesting questions for future research.

Comments

Well, low agricultural productivity in Georgia stems from a wide variety problems. Here are few of them: low priority on the government agenda for so many years, inadequacy of irrigation systems, lack of inputs, lack of technology, lack of knowledge, low commercialization of ag. output, etc. Counterpart Int'l has conducted quite an extensive study on the subject in 2011. It's an interesting read. Here is the document itself http://www.counterpart.org/our-work/projects/analytical-foundations-assessment-for-the-agricultural-sector-in-georgia

[...] ISET poses questions regarding why Georgia’s agricultural productivity remains below 1992 levels, [...]

Interesting questions, and I am sure the incoming Ministers will be pondering how to address this. Some brief responses have been listed at our blog at http://wp.me/p1Vbfq-3Q

Adam, your blog was reposted in http://yfngeorgia.wordpress.com/2012/10/11/agricultural-productivity-in-georgia/. with a rather comprehensive set of comments:

(1) Law and order in the Georgian countryside was arguably amongst the worst in the former Soviet Union until 2003. A lawless situation is not conducive to people investing in their farms, even if they had funds to do so, and so technology that could have enhanced productivity was not introduced.

(2) The civil-war era collapse of the Kolkheti drainage system resulted in vast areas of reclaimed land in Samegrelo, Guria and Ajara suffering indundation. To this date, huge tracts that could be planted profitably to orchard crops are left fallow because the watertable is less than 30 cm below the surface. In country with less than 2 million Ha of agricultural land, this is a major loss of potential that has yet to be seriously addressed. Other CIS countries have not suffered this problem to the same extent to my knowledge, even swampy Belarus.

(3) The degradation of the country’s irrigation system has also held back increases in productivity. In Central and Eastern Georgia, availability of irrigation water when needed can increase gross margins for vegetable producers by over GEL 10,000 per hectare, or more starkly, represent the difference between a harvest and no harvest. Other countries in the CIS either do not suffer the annual July/August drought that besets Georgia every year, or have irrigation systems that function better than Georgia’s.

(4) Blended fertilisers are sold for almost double the world price in Georgia, and custom blends of solid fertiliser are not available. Until recently only one company made nitrogenous fertiliser locally, Rustavi Azot. This contributes to the staggering statistic that only 40% of Georgian farms use chemical fertilisers at all. Yields of common field crops are hence only 30-50% of international norms, independent of seed and other crop care issues. Russia has amongst the world’s largest potash reserves and cheap gas for making nitrogenous fertilisers, and so for farmers to utilise simple NPK fertilisers is more affordable.

(5) The statistics provided consolidate all agricultural subsectors, but productivity changes have not been uniform across all subsectors. For example, physical productivity of the corporate poultry subsector in Georgia is reasonably high, approximately 20% below European standards but still equivalent to poultry juggernauts like Thailand and China. Profit margins from such operations in Georgia are much higher than more competitive markets. Rays of sunshine like this are obscured by the mass of discouraging data from other, larger subsectors.

(6) Some market factors have held back financial productivity, for example the Russian ban on Georgian wine imports. Georgia’s vineyards have made physical productivity improvements over the past decade, but the collapse of the major market means that this won’t be revealed in the World Bank financial productivity figures. Likewise, subsectors like fresh herbs that used to be shipped almost entirely to Russia have suffered major blows, despite making improvements in physical productivity, which will affect the World Bank figures.

(7) Ukraine and Russia have been leasing large tracts of land to several hundred foreign farming companies over the past two decades, who bring modern European and North American technology and management techniques to their own enterprises. Inevitably, neighbours will copy their techniques, and local executives of these firms strike off on their own to put these skills to work in their own ventures. In Georgia, there are only a handful of foreign farming ventures, and most of them are less than five years old, so there has not yet been the opportunity for these ventures to act as de facto extension centres.

No doubt the incoming Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Economy personnel will be pondering these questions over the next few months.

Excellent points – thanks for sharing. I do wonder what happened in Armenia in the early 1990s that put agricultural productivity there on such a different path. Or whether there is something going on with the official productivity statistics, even. Also puzzling is what happened to reported productivity in Armenia in 2010, when it went from around $5,500 per agricultural worker to $4,700 per worker in only a year. There may be some measurement error here.

UNDP Georgia has recently completed a comprehensive analysis assessing and comparing the productivity of agriculture in Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. This work suggests that the infrastructure left from the Former Soviet Union (FSU) is better utilized in Armenia than in Georgia. Particularly, the collapse of the irrigation system in Georgia is one of the key causes for the low productivity there. The concentration of the agricultural machinery is also higher in Armenia than in Georgia. The usage of nitrogen fertilizer is twice as low in Armenia relative to Georgia, however.

But, comparing the rural life stories of our Georgian and Armenian students I did not get the feeling that the Armenian farmers’ standard of living is several times higher than that of their Georgian partners. Both groups are more similar than different to each other .

So, maybe the key to this puzzle is in the other end of the agricultural value chain? Here, I would like to divert your attention from the primary agricultural production to the ability of the countries’ processing industry to add value. A good example is the local (high value) brandy industry, which successfully recaptured its FSU market during the past decade, processes more than 90% of the grape produced in Armenia.

Georgia's economy declined between 1988 to 1994 by 78.2% according the WB WDI. This was the largest decline of all union republics, and also the largest economic decline of any one country in the 20th century. Georgia's economy has only reached 63.54% of 1988 GDP in 2013 (in constant prices). This value destruction was precipitated by tremendous destruction of productive capacity in Georgia. Hence it is not surprising that the productivity decline in the agriculture sector still has not recovered to 1991 levels. Manufacturing decline would arguably show a more serious decline to date.