Far from being the root of all evil, money is one of the most spectacularly useful human inventions. On par with the technology of a wheel, the technology of money has made civilization as we know it possible. But what kind of technology does money replace?

Narayana Kocherlakota (JET 1998) argues that money is a form of memory. Here is an example: John has apples and wants bananas. Mary has oranges and wants apples. Paul has bananas but wants oranges. When John and Mary meet, John can accept money from Mary in exchange for apples and use this money to buy bananas from Paul. Alternatively, however, John can give Mary a gift of apples. If the gift is made, Paul will give John bananas in the future (and be able to receive a gift of oranges from Mary). If the gifts are not exchanged, everyone stays with what they had before.

Viewed in this way, monetary exchange is nothing but an intricate web of gifts. Money is just a way of “remembering” the past deeds – a way for Mary to let Paul know that John has fulfilled his side of the bargain by giving her a gift in the past.

And so, throughout our working lives we accumulate the tokens of memory. Hoping that in the future, when we are no longer able to work, these tokens will remind people of how much they valued the things we did for them in past and will reward us in return.

Surely, this hope may not always be fulfilled. Hyperinflation is one example of such a break of trust, a form of collective amnesia, when the society no longer remembers the past. In one of the worst cases, Hungary in 1946, the memory slates were being wiped in half approximately every 16 hours.

The stores of value, other than paper money, exist, of course. Gold, jewelry, houses, and even skills we acquire over lifetime are used for that purpose. But these things too hold only as much value as the people around us are willing to attach to them - at the moment of time we need to make the exchange.

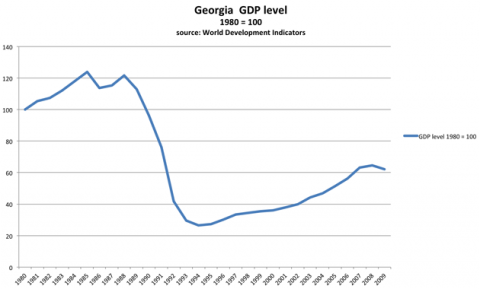

The graph below shows the output collapse in the Republic of Georgia in the 1990s. People lost life savings throughout the Soviet Union. But more than that – all of a sudden like in a fairytale gone wrong, a mathematician turned into a taxi driver and a physicist sold second hand clothes on the street.

On the individual level this would be equivalent to waking up one morning to find that you have lost your place in the community, the friends you trusted, the knowledge and skills you have accumulated throughout your life. Such cataclysms are rare, but once they happen, they affect people profoundly. It may take more than one lifetime to re-establish the society. And both individually and collectively it may take us a while to do the same or better than we once had.

So what is the best store of value? I’m afraid I don’t have a good answer to that. Perhaps the examples of economic cataclysms can remind us of the importance of good institutions. With the severe malfunction of the institutional frameworks, even the very important skills can become suddenly useless, and even the best of people will lose their memory.

Comments

I often find it very instructive to abstract from the veil of money, and to just look at the real economy. In principle any financial crisis does not destroy any real production capacity. Thus countries should in theory be able to wheather any financial crisis without any GDP loss. In theory because any financial crisis will redistribute, change incentives and most importantly will not be meet by an optimal response of the government or central bank.

In constract, the collapse of the Soviet Union also brought some real disruptions. Some in the form of war or suddenly closed borders. But more importantly, by suddenly removing all distortions the Soviet planned economy had.

True, in theory monetary events should be neutral, but in practice they almost never are. This may be because “purely” monetary phenomena (such as hyperinflation) are almost always symptoms of deeper problems in the real economy, and in that sense are never “pure”.

But even if we abstract from all of the accompanying problems, the redistribution of wealth on such a scale is in itself capable of causing a collapse of the real sector. In part because the redistribution destroys internal demand. (Take for example the good old “Zaporozhets” cars: after the collapse of the USSR the demand for them disappeared. And not because the locals no longer wished to buy them - mostly because they could not afford to).

I really liked this post, as it discusses some important concepts that are sometimes not fully understood (or remembered) even by those (for example economists) who should be most aware of them.

The real disruption that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union is the results of many factors. For sure the efforts to eliminate existing distortions, with the consequent massive reallocation of factors of production, played a big role. When distortions are massive, it is almost impossible to get rid of them without causing any negative consequences. This by itself, however, is not enough to explain the extent and the depth of the crisis that hit most transition countries.

The truth is that an economy is not just a machine whose purpose is to maximize output and individuals and institutions are not just nuts and bolts one can easily replace once they are malfunctioning, easily shifting from one model to another. The destruction of institutions and of networks, together with the loss of memory and trust can have (and indeed had) a devastating impact on societies and on countries. An impact that can take very long to be reabsorbed.

With this in mind, one can argue that it was also the incapability of the western economists who were called to give advices about how to deal with transition to see and understand this (maybe because too confident in the "thaumaturgic properties" of free markets or in the general applicability of their economic models - created to explain the functioning of market economies in "ordinary times") who made things worse.

The final outcome, as we know, was a lot of (partially avoidable) suffering and hardship for people living in transition countries. To go back to the original topic of the post, money is just a tool. But we should never forget what it really represents, and what makes it a real "store of value". Otherwise, we are bound to repeat past mistakes. Let's hope this will not happen.

Well said...

Yes, money is an instrument of memory – and not only in terms of finance, but also from the viewpoint of history and linguistics. The name of the British “pound of sterling” keeps the memory of 453 grams of silver stamped with a star – “sterre” + diminutive suffix “-ling”. That must have been an amount with considerable purchasing power.. The etymology of the Russian “ruble” informs of the way the money was made (“Russ. “rubit’” = “the axe”, or “cut”). The Ukrainian “hryvnia” after its rebirth in the 1990s immediately linked Ukraine with its historic past of 1,500 years ago, when this currency was in use. The American (Canadian, Australian, etc.) “dollar” testifies to the common Germanic past of the present-day nations: Low German “daler” (“Taler”) is short for “Joachimstal” – a town where this coin was first minted.

Continuity, tradition, authority are very powerful symbolic aspects of money.

The images we usually see on bills and coins are national landmarks, historical and cultural figures, anything that attests to the continuity of the nation and establishes the link with the past.

Ancient Roman coins in the times of the Republic had images on gods engraved on them. In the Imperial times these were replaced by the profiles of sovereigns.

The Ukrainian hryvnia has images of writers, poets, as well as the prominent rulers of Kyivska Rus and the Cossack Republic.

Although sometimes the desire to convey historical continuity has unintended consequences. If you look at the old 1 hryvnia bill you can still see the image of the ancient city of Khersones lying in ruins - with the prominent inscription: "The Central Bank of Ukraine" :-)

Societies are susceptible to outbursts of collective amnesia - naive attempts to rewrite history, change national symbols, idols and ideology. Bolshevism of 1917 is one example. Bolshevism of 1991 is another. The results are in many way similar - the long-term historical trend quickly reasserts itself along every possible dimension: political, economic, cultural, etc.

I can suggest a way of thinking about the "best" store of value. This has to be something that cannot be taken from you, whether through expropriation or collective amnesia of one sort of another. I have some concrete ideas to put forward, but, first, would like to hear what others have to say on the topic :-)

I read a very nice phrase in a Zoo at Columbus, Ohio, that I believe gives a hint about what could be the "best" store of value.

"When planning for a year, plant corn. When planning for a decade, plant trees. When planning for life, educate your children".

Surely that depends on what you mean by education.

For one thing, there are plenty of people who have given good formal education to their otherwise selfish and ungrateful offsprings.

But even if understood properly, there are other aspects to the education problem – namely, the significant social spillover effects.

For example: in Ukraine nowadays giving bribes has almost become a social norm. When asked how they think their children will live, people usually reply: just like everyone else. The problem for me is that the kind of upbringing I am likely to give to my children will not prepare them to be "successful" and live like everyone else in this type of society.

Our discussion here takes a new and very interesting twist: what is the best store of VALUES (in plural). This has relatively little to do with money and a lot with education and upbringing, including protection from negative spillover effects ("peer effects" as they are called in the economics of education literature). Such protection may be, indeed, extremely expensive.

First, we have to make sure that our kids are surrounded by kids that exhibit positive externalities. Thus, when selecting a primary school we mostly worry about other kids and not the quality of formal teaching per se. Quality of teaching and accreditation begin to play a role at the high school level. We may also want to reduce our kids' exposure to TV (soap operas).

Second, we (the parents) have to devote a lot of our own time - to be with the kids and educate them by example (I don't believe in moralizing).

Actually, storing money or assets for one's children may negatively affect their upbringing (certainly above a certain threshold).

moonshine, you are absolutely right. To some extent spending a lot of time with your children (not passively - as in sitting in front of TV while they are playing in the corner - but actively engaged with them) can even counter the negative "peer effects".

Children whose primary source of love and recognition is at home are more independent-minded, and less susceptible to the peer pressure. But the time and effort this method of upbringing requires on the part of the parents is so great, that very few are even capable of doing it. The parents that do are beyond admiration - in my mind they are true heros.

I don't think storing assets for your children is necessarily a bad thing - it is the focus on material values that may be damaging. Of course the two attitudes are unfortunately very much correlated. (to quote Vysotsky "Кто без страха и упрека, тот всегда не при деньгах":-))

To come back to the post - it seems to me, a good way of investing in your own (and your children's) future is the investment in health. Following yourself and instilling in them the "mens sana in corpore sano" - the gift of good habits, good memories, and good values - that is truly something that can never be taken away!