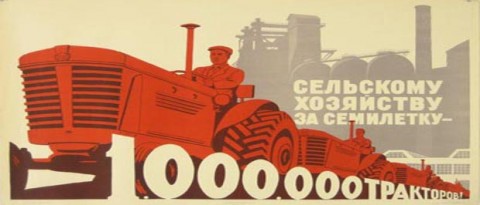

One of the recurring themes of Soviet propaganda was the tractor. Think for example of the film “Zemlya” by Alexander Dovzhenko, which features the triumphant arrival of the first tractor in a village and leaves no doubt that communism is to thank. Fast forward eighty years and this press release leaves no doubt that the President of Georgia is to thank for the arrival of 126 tractors to Georgia.

The tractors will be allocated to 12 service centers across Georgia, giving small farmers access to modern agricultural equipment. It sounds like a great idea, it sounds like a zombie from the Soviet past. Once upon a time, Machine and Tractor stations (Машинно-тракторная станции) supplied equipment to cooperatives, before the equipment was transferred to the Kolkhoz itself.

As with most government interventions the government providing access to equipment could be justified by market failures. If markets would work efficiently small farmers would just purchase equipment themselves, possibly financed by bank loans. This apparently is not happening. One possible interpretation is that small farmers have no profitable use for tractors or other equipment.

More interestingly, if small farmers have a profitable use for tractors or other equipment, it could indicate that they are unable to purchase it because of a market failure. Maybe access to bank loans is the problem, in which case the government should try to address the market failure in credit markets instead of just purchasing tractors. Or it could be because tractors are large investments that are only worthwhile for large farms, or a number of small farmers banding together. But in this case the small farmers could just form a cooperative, and purchase and share the tractor. Or alternatively, private entrepreneurs rent out tractors for a few hours or days to individual farmers. This indicates that the government should encourage the formation of cooperatives instead of just purchasing tractors and providing them via service stations.

Why are service station the worst possible solution? Because there is no built-in guarantee that the tractors will be used efficiently. There are two issues to consider here – incentives and information. Consider small farmers purchasing tractors themselves – either individually or via a cooperative. They face the right incentives as it is in their own interest to use the tractor as efficiently as is possible. They do not face an information problem since in principle they know how the tractor is used most efficiently. This holds even in a cooperative, if the cooperative is well-designed and sufficiently small.

Contrast this with a government service station. The first problem is information, as the manager of the station will have no idea whether it is more efficient to give the tractor to farmer A or farmer B. Farmers themselves have no incentive to volunteer this information, and even worse the manager of the service station will have no incentive to really find out either. Of course there is a solution: Just charge farmers and rent out the tractor at the market rate. But for this the government is not needed, as this service could be provided by private entrepreneurs.

Comments

You may be right in theory. In the Georgian reality, I am not so sure. The donor community (surely, USAID, but maybe also others) have created in recent years a few dozens of privately operated versions of "MTS" (Machine and Tractor Station). These centers provide services to small farmers and farmer cooperatives in their locale.

However, what I heard from people associated with these donor projects (our former students), is that each "MTS" acts as a local monopoly, charging small farmers full monopoly prices given how inelastic (and urgent) is farmer demand for their services. Paradoxically, they do so despite being heavily subsidized by US taxpayers. This, for sure, is not an optimal outcome.

In the current situation, as long as farmer cooperatives remain very weak, Georgia's farming "industry" may be too fragmented, to small, and too seasonal to provide strong incentives for new entry and support competition in farming services. Probably the vast majority of existing "MTS" have been created through donor intervention.

One has to analyze the cost structure in farming services to better understand how many farming service providers can the Georgian market support and what kind of industry structure may ultimately emerge. The fact that fixed costs (price of tractors) and interest rates are very high suggests that the number of firms that can survive in farming services may be very small.

Now, I am not sure what is the best policy response in this situation. You are right that strengthening farming cooperatives should be one option. As far as I can tell, this has been in fact recognized by the government. The tax legislation is about to be changed and donors are ready to support new and existing service coops.

At the same time, having some public provision of farming services may help reduce prices down to marginal cost (plus a reasonable markup to cover the cost of financing, and "normal profit"). At present, farming services are being provided by private entrepreneurs at well above the competitive market rate (even though their costs have been heavily subsidized by US taxpayers). I may be wrong, but in this situation government action could be justified even on theoretical grounds.

Yes, indeed in a monopolistic environment introducing government provided farming services as oompetitors improves the situation. But it is a second-best solution.

I think what is really of interest here is the fact that farming service providers are local monopolies and charge inflated monopoly prices. Farmers are apparently willing to pay these inflated prices. Instead of purchasing farming equipment themselves, financed by bank loans. Or by forming a cooperative. This suggests that access to finance is a problem, and that the barriers to forming a cooperative are high.

More importantly, why is there no entry by competitors? If prices are indeed inflated farming services should be a very profitable business venture! But apparently this is not happening and it is unclear why. If we would understand the why we might be able to develop policy prescriptions.

Of the reasons mentioned - to fragmented, to small, and too seasonal - I think the first two would call for consolidation of farms, not public tractor service stations. The later I think is unlikely, as it would probably justify giving up agriculture.

I agree with Eric. Yes, you'd hope for market entry by competitors, but this is not happening for a number of reasons, and working on the supply of credit may create other distortions.

And sure, farms should be consolidated, but this is not something you can do quickly, for all sorts of reasons. (The tax on unfarmed land had been proposed as well, and may be a very good idea.)

In practice, the availability of more machines in the country-side may help kick-start a good cycle.

Now what one should really do is track empirically what will go on with these tractors...

I think it is obvious why they prefer to rent the tractors instead of buying them … this is all about access to finance.

Some of the rural households do not want to take loans from banks because their incomes are not predictable and it is very seasonal, depends on weather, diseases, market demand, etc. I was young to remember but I heard that there use to be weather guns, which scatters clouds and prevents the hail. We do not have even that now, I’m not talking about the agricultural insurance. Today we have “bad” and “good” years depending how often it rains, because there is no irrigation system anywhere, and what I see in Georgian villages is not functioning irrigation pipes with some parts already stolen for scrap-iron (it is a good business actually, price of 1 t. iron is above 350 GEL, but what is the price of freedom?).

Those who still have some regular income, or they think they do, and want to take a loan, in most of the cases they are rejected by banks; usually they can’t affirm their income. Remember that I’m talking about a typical villager. They do not even go to bank, because they know their chances are almost zero. Mostly, banks only agree to give a mortgage loan, to be on a safe side in such a risky environment as I described above.

There is another way for those people, who were rejected from banks, to get the money, they can take mortgage loan from a private persons for about 5% monthly interest rate. Yes, that high. You can hardly do your business with IRR more than that, that’s why I often hear about the families who lost their houses because they were unable to pay the loan. These unsuccessful stories frighten people around and they become risk averse.

This is a one big chain and government should intervene at some point and try to fix this market failure. They can even charge a small fee for tractors, that would create incentives for villagers to use if efficiently.

I think that idea about consolidation of farms doesn’t have future in Georgia, mentally they do not want any kind of unions any more?

It is a very interesting discussion. Possibly I can contribute somewhat as I am a grown up farm boy, a ‘skilled agricultural worker with exam’ and an agricultural economist and a general economist.

To clarify the issue it might be helpful to look at the experience of other countries, such as Germany. We have small farms in some regions which could be much better of either buying machinery services from machinery contractors, forming a machinery ring with individual ownership of the machines but renting the free capacity to other members of the ring, or even setting up partnerships with joint ownership of the machines. All alternatives had the potential to improve the well-being of many individual farmers. The actual situation shows that many of the farmers suffer from unused capacity of machinery and labor. There is disguised unemployment on many farms and inefficient use of machinery. There are even 30 to 40 percent of full-time farms which make a loss from year to year, indication that they eat up their equity. Hence, these farms would have been better off renting out the land and doing nothing. Of course, there were many extension worker and agricultural economists who tried to convince farmers to join a machinery ring or even to set up a partnership. The breakthrough came only during the last two decades. Note: The use of machineries would have been profitable before! What are the reasons for the delay? Expected profitability is certainly a necessary condition for setting up a private enterprise, but is not a sufficient condition. Uncertainty and risk may be against it.

First, machinery contractors were not at sure that offering the service would have been profitable for them. They have to know whether farmers will actually buy and will actually pay on time (this might be a big problem in Georgia). The contractor has to guess how many hours per year he will be able to sell the service. That depends very much of the cropping pattern in the region and the annual weather conditions. Most likely the contractor will not be able to get agreements on forward contracts and if so he can hardly enforce them. Moreover, he needs specific knowledge how to handle the machineries, including repairing them, and acting as a business man who knows business economics and who can deal with farmers personally. One can imagine that there are few people who are competent in all of these fields.

First conclusion: Even if more use of machinery in Georgian agriculture could be profitable from a macro-economic point of view machinery contractors may not start a business because of lack of know -how and experience, uncertainty about market demand, uncertainty about payment on time of customers.

Second, formation of associations or cooperatives: Whether membership of a coop will pay for the individual farmer largely depends on two aspects: First, how much the individual farmer has to pay at the inception of the coop for the purchase of machinery and for the management of the coop and second, how certain he is about the benefits. The second point bears a significant level of risk. It depends first of all on the rules of the coop and how these are enforced. Moreover, the benefit in individual years can vary significantly depending on the weather and the point of time the individual farmer gets access to the machinery. If famers are not certain that the coop or association will be managed efficiently and in a transparent way, they may not be willing to become member. The trustworthiness of the management is of most importance.

Third, the setting up of machinery rings: There are many machinery rings in Germany nowadays, but it took long to convince farmers. Most important is that the ring is diversified in machineries and faces diversified demands of services and above all has a professional management. It is difficult to start on large-scale in a country which has no experience with these schemes. Note: It may be argued that there are many people in Georgia who can build on their experience in former times where they worked with machineries. However, a contractor or a leader of a coop or a machinery ring has to be not only an expert in technical matters, but also in leading a company. He has to know how to extend the market, increase the use of available capacity, calculate the charges, find out the trustworthiness of client, and make sure that clients pay and so on.

Second conclusion: It is nearly impossible for a founder of a coop or a machinery ring to guaranty that the undertaking will be profitable. There are many uncertainties. No wonder that even clever business men who even would get access to credit have been reluctant to set up respective activities. It should be noted, that the EU Commission is willing to support financially the setting up of producer associations for the first couple of years. The subsidy allows hiring qualified staff. Some of the supported association survived after the gestation period but not all of them.

Is the creation of machinery stations a real alternative?

First, what is the alternative? Continuation as it is? Supporting the alternatives? Continuation as it is seems to be the worst alternative. Setting up a MS would lead to an improvement however as mentioned by some discussants it may undermine the evolution of a private market. To minimize the danger one could foresee the following: MS could be considered as an interim solution. They have to be privatized within a given period of time, say five years. The justification of MS is that they prepare the market for private agents. Farmers learn that machinery rings or machinery contractors or associations or even partnerships can be good for them. In order to maximize these effects MS have to run the business in full transparency. They should have a Supervisory Board with Honorary members of farmers and civil servants. One main task of MS should be that they train young people in the all the wide ranging types of running such an enterprise. It should be clear that the success of the MS largely depends on the management. It might be advisable to send potential would-be leaders of MS and of coops and of associations to foreign countries for some weeks in order to gain experience.

Do farmers have profitable use of machinery? It depends on what is meant under profitable use. If we mean standard definition of profitable use, then the answer might be “no” because in reality rural population of Georgia is very poor and agricultural machinery as well as irrigation are kind of basic needs for them. Agriculture is seasonal and for some activities the season lasts for 4-5 month and farmers should use this time to generate the income for the whole year. Here nobody talks about the surpluses because the main goal is to generate at least some income. The same is true for service providers. We know that farmers who buy machinery should have right incentives and should be interested in generating as much profit as possible. And some of them do this by using their monopolistic power and overcharging farmers. This is one extremeness. The other extremeness is that farmers provide services to their neighbors/relatives for free. The only cost incurred by neighbor/relative is a fuel. Since Georgian understanding of family and neighborhood is very wide, it might happen that the half of the village is served for free. Service centers and cooperatives are very likely to work in the same way.

As to the lack of information it does not seem to be a big problem because in my opinion farmers approaching the service center are similar to each other. The most efficient farmers have their own tractors. So the most vulnerable farmers here are small scale farmers with small number of livestock and small plots of land. They don’t have enough stable income to buy farming equipment or get and pay for loan.

One important point is that in order to make agricultural activities efficient, one needs not only tractors but a lot of other aggregates like mowers, balers, choppers, rakes etc. Tractors without these supplements can be used only for limited number of activities. Finally the amount of money needed is quite large and small scale farmer can afford this only through loan. And if a farmer has a loan then he most probably should serve others for money which cannot be done by everybody because of the above mentioned reasons or lack of time to work on others’ farms during the season. I think that poor access to credit is not a major problem here.

To conclude I think that poverty of majority of rural population and some features of their mentality are the main problems. Farmers believe that they cannot charge neighbors for services. Plus majority of them thinks that cooperatives are useless. In this case government’s intervention can at least increase competition between service providers, thus reduce service prices and increase availability of agricultural machinery in the region. The ideal solution of course would be if farmers could buy the equipment themselves but since this is not possible let them at least rent it.

More clever recent research differentiates between "micro-scale growers" and "emerging farmers". micro-scale growers in Georgian case are "accidental" growers --- people who own 1-1.5ha land around their house. 25 years ago they had "official" jobs and "good" salaries and were "farming" as an optional extra. Now most of them do not have any income from outside their homes and cannot pay in advance for tractor services.

Emerging farmers are farmers who made some money in other sectors or at managerial positions at bigger agricultural firms, have knowledge and invest in small or medium sized land plots. These type of people can pay for agency service.

what do micro-scale growers really want is "again a proper job" outside their homes and not retrofitting their commercially inefficient small orchard. Governments in my opinion should still provide tractor services to this category but meanwhile try to create "outside home" jobs for them. Aid agencies should NOT target micro-scale growers but should assist emerging farmers.

Since majority of farmers in Georgia are micro-scale growers as you call them it might take another 25 years for the government to provide all of them with a proper job. That's because first of all they need to have a proper education to work in schools, municipal centers, hospitals etc and secondly you need to have a lot of these job places in the village. Do we have all these components in majority of Georgian villages? I think we don't. So the problem is very complex and taking into account that in our country unemployment is a severe problem even for urban population I doubt that government can solve it for rural population.

Paying for services is another issue. Farmer can pay for services with money or in kind. The latter is a very common practice in Kvemo Kartli region of Georgia. So it cannot be said that small scale farmers cannot pay for services because in kind can be sold at the market later. Apart from in kind payments monetary payments are still possible because farmer might be selling milk to the milk collection center (Cheese factory), get money for this and then pay for machinery services. That's a common practice in many villages of Samtskhe-Javakheti region of Georgia.

As to emerging farmer, if he has proper education and decided to make a business out of his investment then he should be able to convince the bank that his initiative has high returns and will pay back soon. Businessmen do not approach aid agencies they approach banks.

Thanks for all the great comments! Let's hope at least some students of the class of 2013 will choose agecon related thesis topics. A serious evaluation of the new MTS would be a great topic.

It is a very interesting discussion. Paying for services is another issue. A farmer can pay for services with money or in kind. The latter is a very common practice in Kvemo Kartli region of Georgia. for best reviews of lawngears visit our site https://lawngears.net/