Twenty years ago, on 26 December 1991, USSR broke into 15 pieces, 15 independent states. Amid great hopes, each of these states embarked on a path of transition: from socialism, from one-party state system, from the relative security of a small city apartment, a dacha, and a Lada to… an uncertain future.

For the small Baltic pieces of the USSR puzzle, this road led to EU membership and all of the associated goodies. For many others, however, this may have been a “transition from nowhere to no place” (see the eponymous 2004 bestseller by my number one contemporary fiction writer Victor Pelevin. (In Russian: Диалектика Переходного Периода (из Ниоткуда в Никуда)).

One way to come to this sobering conclusion is to look at the extent to which “democracy” has taken root in the former USSR space. This can be done, for instance, by looking at the so-called “democracy index” compiled by The Economist. According to this index, not a single former Soviet republic progressed to “full democracy” by 2010, though the three Baltic states are getting close – topping the list of “flawed democracies”. Moldova and Ukraine are close to the bottom of the “flawed democracies” list, squeezed in between Mongolia and Namibia. The other 10 are classified as either “hybrid regimes” or outright “autocracies”.

An economist might want to analyze the progress of democracy through the prism of competition policy. After all, democratic governance is often justified as a framework for the free competition of ideas (this is the true essence of democratic politics, which we all love to hate). A political system can be analyzed as a market in which parties compete over peoples’ votes. And just like in any market, we may find that different political system exhibit different degrees of competitiveness.

The more competitive a political system, the more likely it is to produce optimal outcomes (collective choices). Just like in economics, competition implies greater responsiveness to popular demand, better “service”, product innovation, meritocratic hiring and promotion policies.

A rather popular measure of economic competition among firms is the so-called Herfindahl–Hirschman Index, or HHI). It is defined as the sum of the squares of firms’ market shares (expressed as fractions) within an industry.

- HHI takes a value of 0 if the industry consists of a very large number of very small firms.

- HHI takes the value of 1 if the market consists of one firm (monopoly) that dominates the entire industry.

- Higher HHI implies lower degree of competition and greater market power in the hands of the largest player(s).

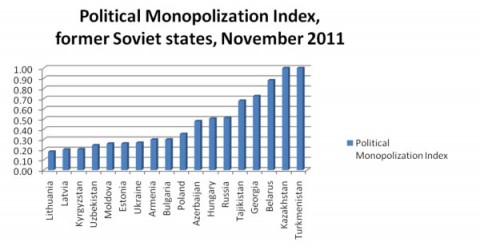

To measure the extent of democratic transition for the ex-Soviet states, we calculated a version of the HHI index which we call HH Political Monopolization Index (HH-PMI). Instead of market shares, HH-PMI uses the shares of seats held by political parties in the national parliaments. It takes the value of 1 for single-party “democracies” and a relatively low value (but certainly not 0) for parliaments populated by many parties of roughly equal size. To provide a benchmark, we added a few randomly selected Eastern European countries. The results are as follows:

This index does not provide an accurate picture of the true state of democratic transition. In particular, it flatters such “democracies” as Uzbekistan and Russia, where a semblance of political competition is carefully maintained by the ruling elites through the creation of “pet party projects “(PPP). See the recent scandal involving the Kremlin puppeteers, the Pravoe Delo (Right Cause) PPP and Mikhail Prokhorov.

Former USSR countries are not doomed to fail as democracies. To the extent their citizens retained any freedom of choice, they can choose differently - by using the ballot box, or by taking their cause to the streets.

Comments

Eric, a nice and valuable effort. But consider this: when Herfindahl index is used by economists (even though not many of the talk about this) it is assumed that there is a free entry to the industry (at least in case when index is 0). Although the same thing applies to creating a new political party the data that you are using is truncated from below but the minimum required percentages to get to the parliament that exist in these countries. So, it actually will be reasonable to look at the election results in percentages and include the parties that did not make it to the parliament. Although it is also true that those parties are not that involved in political decision making, and that the data on complete election results is harder to get.

A very good point, Zak! The version of HH-PMI that I calculated for this post reflects one thing: political pluralism within a parliament (the Uzbek example shows that even this is not always true). Given how imperfectly any elections reflect the underlying political preferences, my HH-PMI index does not do justice to the strength of a country's civil society. The latter could be assessed in the following two ways:

(1) If we are interested in political pluralism as a social phenomenon (strength of "civil society") we should be calculating HH-PMI using data from opinion polls measuring political preferences, not election results.

(2) Another alternative is to calculate HH-PMI using the actual proportion of votes cast for each party (rather than proportion of seats). This method is better than the one based on seat allocation because it removes distortions associated with the minimum threshold requirement, gerrymandering (redrawing of electoral districts), and the formula used to reallocate "surplus" votes (an important problem that is not very well known to the general public). This method also has one potential advantage over method (1): much larger sample size. However, if self-selection into voting is not random (as one would suspect to be the case in "managed democracies"), the results of elections and the index will be highly biased. The second problem is loss of information concerning parties and candidates that were barred from participation in the election (recent examples abound).

This is a good demonstration who you can misuse scientific methods. I am sure that this is terrible proxy to measure democratic transition. One way to check, there are a lot of indexes that measure the depth of democratization, take that variables and just find correlation with these numbers. I am pretty sure it will be close to Zero...Some non-linear associations can be checked as well.

There is also a lot of criticism of those type of indices, so what exactly would lack of correlation be indicative of?

What is better is to find a counter-example, a country where such an index has a high value (much higher than 0.5, the case of two equal-size parties), but where the level of democracy is clearly at an appropriate level.

First, with the exception of Uzbekistan, HH-PMI is quite consistent (or correlated, if Lasha prefers this term) with The Economist Democracy Index that I referred to in the post. Please think of a counter example, as suggested by RT (e.g. a country with a high value of HH-PMI that we would think of as a great democracy).

Second, I am not saying that HH-PMI is a perfect measure of democratic deepening. For one thing, it is subject to manipulation through the PPP mechanism described in the post (see also my comment on Uzbekistan). I would rather say that a low degree of political monopolization (or, conversely, high degree of political pluralism), as measured by HH-PMI, is a good starting point for a democratic polity to emerge, a necessary but not sufficient condition for democratic deepening.

Third, I like HH-PMI for its simplicity and robustness. It certainly does not depend on anybody's subjective judgement.

Fourth, and related to the above point, any other index I am familiar with is calculated as a weighted average of scores a country gets on a certain set of characteristics that are that are deemed important for democracy. Such indices are subject to criticism for three obvious reasons:

a) They are based on "expert" surveys. The results therefore critically depend on sample size and choice of experts (who are surely not selected at random);

b) There is no universal agreement on which characteristics define democracy. For instance, are access to education and income inequality important attributes? Some would say that having access to healthcare, job and food security are more important attributes of democracy than having the right to vote every four or five year;

c) A priori there is no correct way to assign weights to particular characteristics of democratic governance (freedom of media, freedom of political association, freedom of elections, etc.)

There was a question raised on Uzbekistan -- is that really 0.2?

The true value of the HH-PMI index for Uzbekistan should be 1. Uzbekistan is a great example of the PPP manipulation mechanism at work. All four major parties that combine for 135 seats were approved (sic!) for participation in the 27 December 2010 election support president Kerimov, there is no real opposition in the country. Moreover, according to Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uzbekistani_parliamentary_election,_2009%E2%80%932010, "several opposition politicians have alleged that all candidates also had to be approved by the government before they would be placed on the ballot". A fifth party ("ecological movement") was granted fifteen seats in the parliament, one seat per region, without participating in the election.

It would be interesting to correlate your HH-PMI (corrected for the "pet party" factor) with the weighted average of HHI for countries' major industries and a measure of economic diversification. I have a feeling the correlation would be significant and positive...

You are welcome to try, Yasya

Eyeballing the data, it appears that you are right with the exception of Belarus and Georgia. Both are quite diversified (not having any natural resources to speak of) and yet their parliaments are dominated by a single party. Other than that it does seem that having a large natural resource extraction sector helps establish a political monopoly of sorts.

Without having done the regression I already have a theory about it :-)

Economic interests necessitate political representation. (e.g. the rising merchants and industrialists in Great Britain pushed for the Reform Bill of 1832; the newly emerging "managerial class" in Ukraine helped finance the Orange Revolution). Therefore, the more diversified the country's economy and the more competitive the industrial structure, the more diverse are economic interests, and the more plurality and competitiveness one may see in the political system.

(Of course a diversified economy does not immediately translate into a diversified parliament. For example, in Georgia the "middle class" may still be relatively week economically as well as politically, but this will change as the country develops).

There is a potential feedback effect from political competitiveness to the industrial structure as well: tightly controlled parliaments would tend to pass the laws which help concentrate economic power in the hands of the select few.

The countries with large natural resource endowments seem to be an interesting special case. One may argue that in these countries the political systems are "natural monopolies", as the economy consists of only one naturally monopolistic industry.

That said, however, I myself do not much buy into the argument of "naturally autocratic" states. The feedback effect mentioned above can seriously entrench the power of the few, making the economic (and political) diversification all but impossible without a revolution of sorts.

An excellent theory. Here is a possible refinement (to account for the Georgian case).

To generate political pluralism you need economic diversity AND organization/cohesion/leadership attached to each sector.

Small traders and restaurateurs (the bulk of Georgia's emerging middle class) are inherently unorganized, atomized and lacking prominent leadership (small traders are not made of the right material to provide leadership, that's why they stay small). Small traders are very good social material to support the emergence of dictatorships.

Economic diversity can translate into political diversity if the various economic interests are sufficiently organized and endowed with sufficient resources to compete for power.

Absolutely!

It seems that taking advantage of the economies of scale is beneficial not only economically. It is instrumental in acquiring a political voice.

Borrowing from Industrial Organization theory we may talk about the “optimal firm size” and the optimal level of economic diversification to create a system of political pluralism with effective checks on the executive power...

Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Moldova before Estonia, Poland, Hungary. Moreover, Azerbaijan and Armenia before Hungary... If all these do not seem very strange to you, then definately you understand democracy differently than I do [even in a very technical sense, I do not undesrtand . I am sure pretty you think that in 1990s Microsoft was monopolizing market and harming consumers

Lasha, please read my other comments. Uzbekistan is a special case. Its true index is 1. Kyrgyzstan parliament is quite fragmented, reflecting a true plurality of political preferences. It is quite democratic in this sense (there are no restrictions on any freedoms, and people are free to speak, form associations, parties, etc.). It surely has a long way to go in terms of institution building, poverty reduction, etc.

In any case, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Estonia, Poland and Hungary have HH-PMI values below 0.5, which allows for ideas to be contested. In countries with HH-PMI values below 0.5 the largest party would most likely have to form a coalition. This in itself forces a political bargaining and compromises. The lower the index, the harder it becomes to build a coalition, pass laws, accept budgets, etc.

Lasha, please read my other comments. Uzbekistan is a special case. Its true index is 1. Kyrgyzstan parliament is quite fragmented, reflecting a true plurality of political preferences. It is quite democratic in this sense (there are no restrictions on any freedoms, and people are free to speak, form associations, parties, etc.). It surely has a long way to go in terms of institution building, poverty reduction, etc.

In any case, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Estonia, Poland and Hungary have HH-PMI values below 0.5, which allows for ideas to be contested. In countries with HH-PMI values below 0.5 the largest party would most likely have to form a coalition. This in itself forces a political bargaining and compromises. The lower the index, the harder it becomes to build a coalition, pass laws, accept budgets, etc.

By the way, Eric, have you calculated the values of index for the USA, UK, New Zealand, Germany ...?

Eric, I understand your points. You are right while telling "It is quite democratic in this sense". My critics concerns the idea that you put in the words "in this sense". I think that the index "in this sense" does not capture the "true" sense of democratic transformation.

I am not a fan of democratic political system, but for me it is associated with equality before the law; civil liberties; human rights; judicial independence; freedom of political expression; freedom of speech; freedom of the press. In this sense, it is difficult to except the results.

"The lower the index, the harder it becomes to build a coalition, pass laws, accept budgets, etc." - Yes, in the environment where democratic institutions already exist and work, but the study covers countries where political competition is more associated with rent-seeking.

Thank you for replies.

Just to reiterate: an index of political pluralism such as HH-PMI, does not capture "the true sense of democratic transformation". It is a necessary condition for a true democratic transformation to occur. I find it very hard to see how "equality before the law; civil liberties; human rights; judicial independence; freedom of political expression; freedom of speech; freedom of the press" can be promoted and protected in a single-party "democracy".

Also, as someone who reads Ludwig von Mises, you should appreciate the value of competition in any sphere, including politics. Political competition, as we all know, is particularly vulnerable to government intervention through meddling with constitutional and electoral law, licensing and registration of parties, legal prosecution and expulsion of political opponents, abuse of administrative power and resources (money, access to media, etc.). When HH-PMI is above 0.6 (which is equivalent to one party having more than 70% of the seats) you can be sure that some if not all of the above tactics are being employed.

A side remark: the lower the index, ceteris paribus, the harder it becomes to build a coalition, pass laws, accept budgets, etc., in any environment. Whether democratic institutions are developed or not. I believe this is a theorem in game theory (the "core" is smaller).

Your point on rent-seeking suggests an interesting topic for research: how does political competition affect rent-seeking behavior and welfare?

Many other commentators have pointed out the flaws of the HH-PMI, so there is no need to give further examples of countries where it would misstate the democratic development. In fact this just shows how difficult it is to measure democratic development in an "objective" way.