One of the definitions of a safety net that one can find on the internet is the following: “a net placed to catch an acrobat or similar performer in case of a fall”. This brings to my mind images of thrilling performances I saw at the circus when I was a child. I have to admit in most cases a safety net was used. It was only removed on some rare occasions, and the increased tension became palpable. We knew that only the best acrobats could dare perform in those conditions because even a slight mistake or distraction could lead to disastrous consequences.

Born in this context, the term safety net has soon been extended beyond circuses. The same internet source, right below the standard definition adds: “fig. a safeguard against possible hardship or adversity: a safety net for workers who lose their jobs”.

Imagine you are a European worker in a time of crisis. You are the only breadwinner in your family and you become unemployed. Your families situation is going to worsen significantly, but you know that – at least for some time - you and your family will be able to survive thanks to your unemployment benefits and to other forms of social support. In the meantime, hopefully, you will be able to get a new job – maybe thanks to the help of a public employment agency - or will at least be admitted into some publicly sponsored training program increasing your probability to get back to work.

Imagine that, instead of being fired, you get sick. Luckily most of the costs for your care will be covered by the public healthcare system. You will continue receiving your salary (with a reduction as the length of the period of sickness goes beyond a certain number of days) for at least a few months, typically until you can go back to work. If your sickness is really serious, at some point you will not receive compensation but you will keep your job unless you stay away from your workplace continuously for a very long period. Should you lose your job, you will still be able to rely, for a while, on unemployment benefits and on additional forms of social support. Your family will be suffering of course, but at least you will be able to “gain some time” to try finding a solution.

Now imagine a different scenario.

You lose your job. You get one month severance pay but no unemployment benefits. The labor market is hardly creating new jobs, so you have a high probability of not finding a good job and will have to either accept being unemployed for a long period of time or to work in badly paid temporary jobs, maybe in very dangerous working places (because nobody is in charge of checking working conditions). In case you choose not to take the risk, and to try looking for safer jobs, most likely during your unemployment period you will not receive any training and certainly no support from (non-existing) public employment agencies.

What if you are sick? All the healthcare costs fall on you. If you have private health insurance, you get some assistance. If not, you have to use your savings in order to get some treatment. You receive one month worth of salary, after which your employer is free to fire you without having to give you any compensation. So you suddenly find yourself sick and not only unable to help your family but being a burden to them, with no public support and no income. To be fair, you might receive some sort of assistance, after you have applied to the government for support as a needy household, if your situation has deteriorated so much that you cannot ensure even your subsistence (maybe by selling assets). But don’t expect the support to be that high.

The picture looks much different, doesn’t it?

This second case is not that of a fictional country. It is just a representation of the conditions of most workers in Georgia.

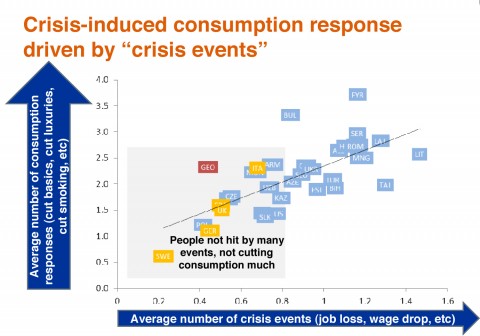

If you keep this in mind, you will not be surprised when looking at the following pictures taken from the latest EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) Transition Report, titled: “Crisis and Transition: the People’s Perspective”. The tables and pictures included in the report are based on a series of household surveys conducted by EBRD in a number of transition countries plus a few selected countries of Western Europe. The aim of this study was to study how crisis had affected household’s welfare in order to draw some conclusion about the potential vulnerability of countries and households to future crises.

In this first graph, Georgia (in red) stands out quite a bit above the regression line. This is defined as an “outlier”. In this case being an outlier means that Georgian households, despite having been themselves hit by a relative small number of negative events, appear to have suffered much more than households in similar situations in other countries. In other words, they were forced to cut their consumption much more than households in other countries.

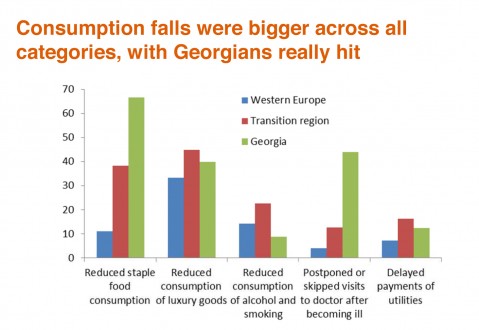

The second graph (below) allows us to see where Georgian households had to cut their consumption. Of course, cutting the consumption of luxury goods is not the same as cutting on food or healthcare. Looking at the second picture, if possible, makes things look even worse. Most households had to cut exactly where one would hope they would not have to: staple food consumption and visits to doctors.

Neither of these cuts bode well for future Georgian households, as they are likely to have long lasting (negative) effects on them. Especially as a new world crisis seems to be approaching.

Why this discussion about Georgia and safety nets? Because for some time now Georgia has been presented consistently as a showcase country with an impressive reform track (including an extremely liberal labor market reform that has drastically reduced all forms of workers’ protection) and equally impressive growth rates.

Much less has been said about how Georgian people have been affected by these reforms. For sure the picture that emerges from the EBRD study is of a country where households are extremely vulnerable to any slowing down of the economy or worsening of the macroeconomic conditions. Much more than in most other countries.

Again, looking at the EBRD study, we can see that this is related to at least two factors: on one hand the extremely weak safety net provided by the state; on the other hand, the limited success (so far) in translating high growth rates into a substantial amount of new, “good quality” jobs.

This is what led the EBRD, after presenting these results to suggest the following two key priorities for the Georgian government.

“…to create a basis for export led growth… […] but also to establish an effective social safety net”.

I would like to conclude with my personal answer to the question: “who needs a safety net?”

A lot of people, I would say, especially in times of crisis like these ones. After all, even the best acrobats would not dare performing all the time without it, especially when they are trying their most dangerous performances for the first time and when preconditions are less then perfect. Why? Because the cost of failure would be too high.

Like in the case of acrobats – even more, as they are not risking their lives only – policy makers have the responsibility of taking into account in their evaluations what could go wrong and think of ways to minimize negative impacts on the population.

Most economists would agree that only a sustainable increase in the welfare of citizens (including the most vulnerable ones) is the true sign of development of a country in the long run. Assuring this, as someone sometimes seems to forget, requires also creating and maintaining – especially when markets are less than perfect, a solid social safety net.

Comments

There are a lot of problems to be dealt with, definately... But approach "Nothing or Everything" is not an economic way of thinking.

It is very nice to talk about safety net. Everyone would like to get extra money at hard times. But at what price??? What is the cost of providing social benefits? Not only direct costs, but what happens with incentives as well?

"In the economic sphere an act, a habit, an institution, a law produces not only one effect, but a series of effects. Of these effects, the first alone is immediate; it appears simultaneously with its cause; it is seen. The other effects emerge only subsequently; they are not seen; we are fortunate if we foresee them"

"What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen" - Bastiat, Frédéric

Safety net is a attractive name, but the synonyms (things that are not seen while talking about SAFETY NET) of it are: Higher taxes, rigid labor markets, High government spendings... Now, there are a lot of solid scientific, empirical research about the relations between these variables and Economic growth...

Lasha, two points:

1. Social safety nets do imply somewhat higher taxes, somewhat more rigid labor markets and somewhathigher government spending. However, each society or polity can decide how much safety to provide and at what price (in terms of higher taxes, spending, etc.). EBRD's and Norberto's point is that Georgia provides 0 (zero) social insurance. Now, while Georgia can not be as generous to its poor as Sweden it could surely provide a bit more than 0 (in a targeted way) without causing too many distortions. In fact, it could do so in a budget-neutral way at the expense of e.g. a few roads. Of course, there is a trade off between higher GDP (tomorrow) and jobs, health or education for the poor (today). This very trade-off is at the core of politics in most countries. The Georgian people will face this trade-off when they go to vote in a few months. They will have an opportunity to reconfirm their choice in 2013.

2. My second point is that social safety nets imply not only costs but also benefits. And very importantly, these benefits accrue not only to the poor but also to the elites. This is why the latter have started introducing social safety nets in the 19th century, well before the rise of modern democracies. [To the best of my knowledge, one of the first states to introduce social safety nets was Bismark's Germany which was anything but democratic.] Essentially, social safety nets are the price the rich and powerful are willing to pay in order not to be hated, to ensure protection of (their) property rights and political stability. Coming back to my previous point and Georgia, I would argue that by providing zero social insurance, the Georgian "rich and powerful" are buying very little love, property rights protection and political stability.

Several points to be recalled:

The current problems of Greece, Spain, Italy. Reasons?!

Wealfare State (Socialism) is attractive and politicians definately know this. Public choice?!

Even in the language of neo-classical economics, Employment benefit is not a public good, why it should be provided by government? Private isurance markets, personal responsibility?!

I am not against the idea of safety net (I also do not like to see paople in trobles), but it should be based on correct incentives, personal responsibility and free markets.

I think Greece, Spain and Italy are instructive. As is Sweden. Designing a social safety net that sets the right incentives and doesn't threaten fiscal sustainability is hard. As is making sure that social security is not expanding at an unsustainable pace by populist governments.

Is it likely that Georgia is a country that could get it right? I have my doubts, given the low level of social capital, and given the lack of (constructive) political competition.

More importantly, no country seemed to have gotten it right. Instead, the more successful countries had to fix their social welfare system over and over again. The less successful countries such as Greece did not.

Great to have a nicely developed social safety, but a country also needs the political institutions and culture that will fix and reform social welfare whenever necessary.

Michael,

"More importantly, no country seemed to have gotten it right. Instead, the more successful countries had to fix their social welfare system over and over again. The less successful countries such as Greece did not."

Exactly! Moreover, no country will manage to get it right, at least, under democratic system (to many problems to write them here). Advising Georgia to have employment benefit system is destructive. Developed countries can bear the system somehow, even they have or will face serious problems...

Also, I do not think that Sweden is an instructive case in the good sense.

One more thing, when it is difficult to design something, it should be left. We enjoy many things that are the results of spontaneous order. Government is not a mechanism to coordinate in a good way and set correct incentives.

Interesting difference between the staple food and the alcohol. Goes well with my conspicuous consumption paper.

I am happy to see that my blog post has stimulated a lively debate, which was exactly its purpose.

From the discussion it has clearly emerged that choosing the optimal level of social protection requires dealing with a potential trade-off between equity and efficiency considerations. The existence and the importance of this trade-off is one of the points raised more often by those who desire a small and shrinking government role. Still, it can be argued that the trade-off does not always exist. This means that in some cases it is theoretically possible to increase equity and efficiency at the same time.

In absence of a safety net, poverty is a concrete risk for many individuals who live in developing countries. Even worse, poverty can be self-perpetuating and damage not only poor individuals but also the development perspectives of the country in which they live. Growth by itself may not be sufficient to solve these issues. The extent to which growth leads to true and sustainable development depends crucially from the characteristics of the process and from how benefits from growth are distributed across the members of a society. For all of these reasons, any forward looking policy maker would try to minimize the risk that a substantial part of the population falls into poverty when negative external shocks hit. The risk, otherwise, could be that an initial shock triggered a dangerous and vicious circle of growing poverty, inequality and underdevelopment. In such a situation, an excessively small government, with limited functions and a little budget, would not necessarily lead to a faster development than a more active and larger one.

Of course, devising a well functioning welfare system (which does not necessarily mean turning a market economy into a socialist economy) can be difficult and maintaining it can be costly. However, these difficulties and costs have not prevented the countries we define now as "developed" from developing. Obviously, we cannot know how these countries would have performed without a welfare state. What we can say for sure, however, is that they did not perform too badly having one if they are now “developed countries”. One might even argue that their welfare systems helped those countries achieving what they achieved in several ways (for example by increasing social cohesion and mutual trust, encouraging risk-taking and the accumulation of human capital, reducing social conflicts and political instability to cite a few).

It has been argued that, even in the most developed countries (take Germany for example) the welfare state had to be adjusted and revised from time to time. This is certainly true, and for sure more adjustments will be necessary in the future. This, however, is not a distinctive feature of the welfare state and of modern societies. All human institutions have always required revisions and adjustments, exactly because of human nature and of the changing environment in which societies and economies live and develop. When a new institution appears it is typically because it has to satisfy some needs of the society that creates it. As the society evolves, individuals adapt and the environment changes, old institutions need to be adjusted as well. Incentive structures that were optimal at a given stage have to be rethought and modified.

Even the market is an institution and, as such, is not perfect. While it is true that letting market forces free to operate can help using scarce resources more efficiently, it is also recognized by most economists that markets can fail as well and cause problems at least as serious as those associated with a “big government” (especially for developing countries). Failing to recognize this, hoping that some invisible force will take care of everything, is not only conceptually wrong. It is a recipe for disaster.

So, are we bound to fail whatever path we choose? Not necessarily. But we must recognize that no existing system or institutional setting is perfect and no alternative is costless. Success requires a continuous monitoring of the economic, social and political environment, and the willingness and the possibility to intervene when necessary. All potential costs and benefits of alternative institutional arrangements and of alternative policies should be understood by the public. It is the responsibility of economists to make these costs and benefits clear. It will be then up to the people (or societies if you prefer), to decide what path they prefer to take. Be it with or without a safety net.

I actually stumbled right here by a different page as well as thought I might as well examine things out there. I like things i see and so i am just following you. Look forward to discovering your web page again.