Protectionism and any kind of import restrictions have supporters in every country, and Georgia is no exception. Recently, I attended a lunch meeting on the need for an antidumping law, organized by Georgian Lawyers for Independent Professions, Governing for Growth (G4G), and the Society of Free Individuals. Participants from different sectors and institutions presented their views on the possible economic consequences of antidumping regulations currently being discussed by the Georgian government. From an economist’s perspective, I believe there are number of factors to be considered and analyzed before the final decision to adopt the law is made. The rationale behind anti-dumping duties is to save domestic jobs, but they can also lead to higher prices for domestic consumers and reduce competitiveness of domestic companies on international markets.

|

| Gigla Mikautadze of Private Sector Development Research Center at ISET-PI attending an antidumping law discussion held by EPAC. |

According to the Government of Georgia, a draft law on antidumping is now complete, but the Ministry of Economy is still considering the risks of the new regulation. “The Antidumping Law is elaborated in accordance with the WTO regulations. However, everyone should realize that this law is not a panacea,”1 said Dimitry Kumsishvili, Vice Prime Minister of Georgia. The stated purpose of the draft law is to help ensure competition by imposing protective measures on imported goods that the government believes are sold below “normal value,” defined as the market price in the exporting country.

The idea of antidumping finds its roots in the United States, where the Antidumping Act was enacted by the US Congress under the heading of "Unfair Competition" in 1916. Once antidumping was effectively applied in a number of cases involving troublesome imports, and local producers benefited from it, supporters of this type of regulation started to grow, especially after wide scale trade liberalization which put competing domestic industries under bigger pressure.

| Main users of antidumping | Main targets of antidumping | ||

| India | 38 | China | 63 |

| Brazil | 35 | South Korea | 18 |

| Australia | 22 | India | 15 |

| USA | 19 | Chinese Tapei | 13 |

| EU | 14 | USA | 11 |

| Mexico | 14 | Malaysia | 10 |

| Canada | 13 | Thailand | 9 |

| Indonesia | 12 | EU | 8 |

| Turkey | 12 | Turkey | 8 |

Source: www.antidumpingpublishing.com

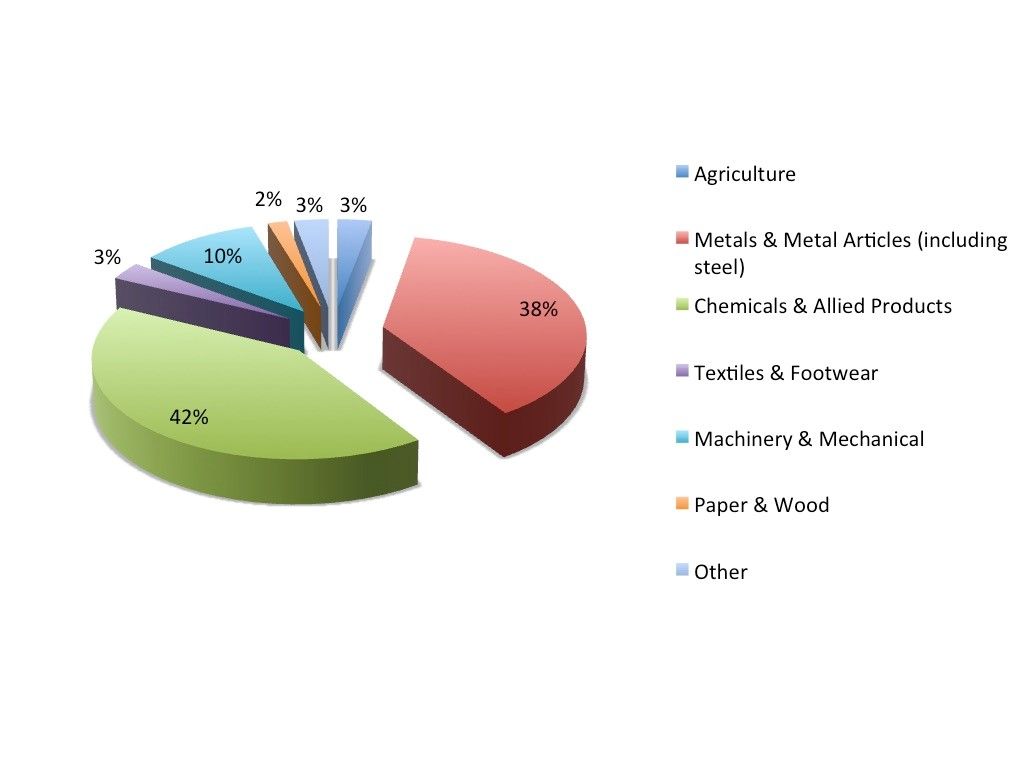

It is also interesting to analyze the sectors involved in antidumping investigations. The main appeals happen in traditional capital-intensive industry sectors, such as metallurgy, chemicals, machinery etc., due to the inflexibility and high fixed costs of these industries. Usually, these sectors are also quite labor intensive, hence very sensitive from a social policy perspective.

Governments usually impose antidumping duties based on investigations. An antidumping investigation occurs when the proper state agency, upon a valid complaint from a local industry, tries to determine whether imported goods are being sold at below-the-price in the producer country, i.e. being 'dumped'. These investigations require significant human and institutional resources in order to gather solid evidence of antidumping against suspected importers.

Recently, Georgia itself became a suspect in an antidumping case when, in 2015, the EU Commission initiated an antidumping proceeding concerning imports of certain manganese oxides originating in Georgia. In the absence of reliable data on domestic prices, export prices from Georgia in the EU were compared to the prices in the United States of America and to the constructed normal value which takes into account the estimated manufacturing costs, sales, general and administrative costs, and profit in Georgia. At the end of 2016, the complainant had to withdraw their claim, since the investigation had not brought to light any evidence of dumping, and the case was closed.

Going back to the need for an antidumping law in Georgia, in evaluating the threats of dumping, we have to take into account the size of the local market and the insignificant role of the country on the world market in all industries. It is very doubtful that Georgia faces a genuine threat of dumping from its trade partners. During the last 25 years, there has been no evidence of dumping, aside from the cheap import of various products which are never welcomed by local producers, but which do benefit consumers and producers who use the imports as inputs to their own production.

Supporters of antidumping usually question whether the pricing practices of foreign firms are fair, which, in my opinion, is the wrong question to ask. Before enacting any antidumping law, we should be asking whether it is in the national interest to provide protection for domestic producers. Even if importers’ prices are “unfair,” that does not necessarily mean that protection is in the national interest.

In addition, while thinking of antidumping regulation, we must not forget its impact on bureaucracy. As mentioned above, antidumping actions are based on comprehensive investigations, requiring well trained staff and a strong institutional set-up. “Antidumping is a bureaucratic, not a legal process,”2 says Finger in Antidumping: How it Works and who Gets Hurt, and it will definitely increase compliance costs and the risk of corruption. The main goal of Georgia at this moment is to improve the business environment in order to promote foreign direct investments and economic growth. Therefore, any kind of new regulation must be considered carefully.

To summarize, lawmakers should analyze not only the benefits created for particular interested groups, but also the costs and losses for other players on the market. Procedures should be clear about the costs of the requested protection, and the identities of the persons or groups who will bear those costs. For instance, if the targeted imports are needed materials, more expensive import means higher costs for producers, and will possibly effect domestic jobs. It is obvious that the government will always be under pressure from local producers, interested groups, and lobby organizations demanding import limitations, but before imposing any restrictions they must review such potential issues in detail and decide whether they deserve relief from the liberalization policy.

1 http://www.economy.ge/en/media/news/dimitry-kumsishvili-comments-on-antidumping-law

2 Finger: Antidumping: How it Works and who Gets Hurt, the University of Michigan, P. 23, 1993

Comments

The purpose of anti-dumping regulations is not only to serve some lobby groups, as claimed in this article. In Georgias specific case, such regulations could help attract new (foreign and domestic) investment in modern agriculture. The logic is very simple: investment is a risky endeavor. To the extent that the government can reduce systemic risks, more investment will happen.

The WTO affords its members with a number of protective (not protectionist, but protective!) measures to ensure a stable, less risky environment for domestic businesses. Such are, for example, safeguard measures __ defined as “emergency actions with respect to increased imports of particular products, where such imports have caused or threaten to cause serious injury to the importing Members domestic industry (Article 2). Such measures, which in broad terms take the form of suspension of concessions or obligations, can consist of quantitative import restrictions or of duty increases to higher than bound rates. They are one of three types of contingent trade protection measures, along with anti-dumping and countervailing measures, available to WTO Members. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/safeg_e/safeg_info_e.htm.

When applied, contingent trade protection measures can and are routinely challenged in courts, adding a degree of transparency to the whole process (as described in the article in case of Georgian manganese exports). These measures can also be very short in duration (for example 3-6 months), not giving lobby groups the opportunity to hide behind protectionist walls.

The article further claims that during the last 25 years, there has been no evidence of dumping, aside from the cheap import of various products which are never welcomed by local producers, but which do benefit consumers and producers who use the imports as inputs to their own production. How does the author know that there has been no evidence of dumping? There have certainly been suggestions, including in ISETs own Food Price Index publication, that Turkish producers may have been dumping their agricultural products on the Georgian market following the Russian ban on imports from Turkey. The whole drama of the current policy discussion is whether or not Georgia should adopt a legal framework allowing for such instances to be properly investigated. Until then we wont know whether there has or has not been any evidence of dumping. The author, however, seems to know the answer without any investigation.

Eric, many thanks for your comments.

I agree, that the declared goal of antidumping is to “protect” the local producers, but very often it is used for other, political purposes. Yes, it is pure politics when government protects a single producer or sector, but does not consider effects on others. In most cases, it is impossible to quantify all costs and benefits, and make them comparable. This is why antidumping is difficult to evaluate.

You are right. Investors need guarantees, but I do not think that the Government has to guarantee a minimum price. Even if the government prevents cheap import, what about other local producers? Can government forbid so called “penetration strategy” and prohibit local producers to set “unfair” prices? This is also a risk, but the investors are usually aware of it. So the state should ensure high competition instead of imposing price controls.

But in general, dumping can be harmful for a particular producer only, if it is permanent and targeted. The short-term actions cannot damage seriously and they cause insignificant shocks. Selling product permanently at a price that is lower than cost, causes loses for the importer. The only reason why the importer would follow the dumping strategy is to eliminate competitors and to become a monopoly. In a competitive market with many players, it is almost impossible a) to “kill” all competitors and b) to remain a monopoly in long term, if there is free access to this market.

The statement on missing dumping cases does not belong to me. It was mentioned by the representative of MoESD. You would ask, how they can know this. They conducted simple investigations for every claim they received from Georgian companies. 2 products were mentioned during our meeting: flour and eggs. In both cases, neither import price was lower than local price, nor was the share of import significant.

I think, we should not spend our resources looking for a black cat in a dark room. We should rather concentrate on other important things, namely, how to increase efficiency and how to become more competitive in international market.

It is not true that only permanent and targeted dumping can be harmful to domestic producers. Three-four months of dumping could push into bankruptcy a new greenhouse project carrying millions of dollars in debt. If forced to sell below its own cost, it may not be able to repay its debt (unless the owners can inject additional cash).

It is also not true that dumping is necessarily or only about killing competitors. In case of agriculture, dumping is mainly about getting rid of excess production which has a short shelf life. Fruit, vegetables or eggs would be classical examples. For example, when Russia closed its market for Turkish products, Turkish agribusinesses must have tried to sell their products elsewhere, at any price. It was not about killing competitors, but rather minimizing losses.

If you are not the author of a particular statement in your article, you should cite your sources, be it MoESD or anybody else.

And, by the way, nobody - neither me nor WTO - suggests governments should be in the business of guaranteeing minimum prices. WTO rules allow governments to insure domestic producers (and future investors) against unfair competition and/or help them in case of emergency.