Back in 1991, I attended a big “Does Socialism Have a Future?” conference hosted by my alma mater, the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The session I remember most vividly featured a Hungarian dissident, a poet, ridiculing ineffective communist propaganda. “Communists”, he told a sympathetic audience, “tried to convince us that jeans can cause impotence in young males, and that Coca Cola is bad for people’s health”. At this point, a trembling female voice could be heard in the back of the conference hall: “But Coca Cola is bad for people’s health!

◊ ◊ ◊

The introduction of capitalism to Russia and the rest of the communist block was spearheaded by the arrival of coveted Western consumer goods. Capitalism came in several flavors. I will never forget the peppermint gum – a single piece! – offered to me, an 8-year-old Soviet kid, by a good-hearted Finnish tourist. This was an amazing stroke of good luck. Attracted by Russian vodka, binge-drinking Finns inundated St. Petersburg in the 1970s, but few of them distributed peppermint gum.

A more systematic exposure to capitalistic flavors started in 1974, with the opening of the first Soviet Pepsi factory in Novorossiysk. Since rubles, for which Pepsi was sold in the Soviet Union, could not be converted into dollars, the capitalist genius found a creative solution: to barter Pepsi for Stolichnaya vodka (one liter of Pepsi concentrate for one liter of Stolichnaya), and – later – for Soviet warships and submarines.

It took 16 years, as well as Glasnost and Perestroika, for another major American brand to land on the “dark side of the moon”. When the first McDonald’s fast food restaurant opened in Moscow on 31 January 1990, it served a mind-boggling 30,000 visitors in a single day, setting a new world record. Dying for a barbecue-flavored bite of American capitalism, Muscovites queued for over 6 hours outside the restaurant. Inadvertently, while doing so, they had their backs turned towards the statue of Alexander Pushkin, a key symbol of Russian literature and culture.

While Pushkin might have been turning in his grave at this bizarre sight, a 1990 commercial on Soviet TV claimed that the “new generation [of Soviet citizens] chose Pepsi”. In more than one way, consumerism, symbolized by Pepsi and McDonald’s, merely substituted for Marx and Lenin in the mind of Homo Sovieticus, as beautifully satirized in Victor Pelevin’s bestseller Generation P (Homo Zapiens in Andrew Bromfield’s English translation).

◊ ◊ ◊

The transition from socialism to capitalism was anything but linear or smooth. Some aspects of transition – privatization of state owned property, price liberalization and even macro-stabilization – were achieved within three-to-five years by most newly capitalist states. What followed, however, was a far cry from the imagined consumerist heaven, at least for the vast majority of rank-and-file ex-Soviet citizens who became increasingly concerned with simple survival. Not Pepsi. Not McDonald’s. Physical survival given the absence of jobs; with no security from crime; no social safety nets; and, not infrequently, no electricity either.

Yet while post-Soviet economies and politics may often look like a caricature of the free-market-and-liberal-democracy vision, Western-style consumerism and fascination with Western consumption patterns remain an important ideological fixture of the Eastern European landscape.

Consumption of alcohol is an interesting case in point.

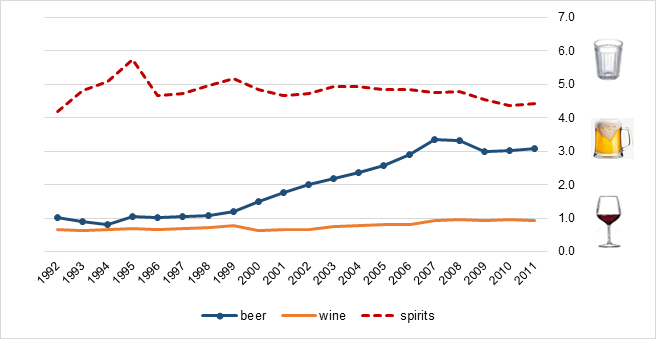

Figure 1: Per capita(*) alcohol consumption (in liters of pure alcohol) in former Soviet Union, 1992-2011

Soviet alcohol consumption was dominated by strong spirits, such as Russian vodka, Georgian chacha, and Armenian “cognac” (brandy). Wine was second, mainly consumed in the traditional vine cultivation areas (Georgia, Moldova, Crimea). Finally, though quite popular with Soviet males, beer was third – available on tap or by the glass through specialized kiosks and street kegs (much like kvass).

With all government restrictions on the production and sale of alcohol removed, the start of the transition to capitalism and democracy was associated with a large spike in alcoholism and deaths from related causes. Consumption of spirits remained very high until 2011 (the last year for which we have WHO data), although it shows a gradual decline. Throughout the same period, we observe a very moderate increase in the consumption of wine, and a very strong growth in the consumption of beer. This data suggests that the young Pepsi generation not only adopted Pepsi but also the associated life style – hanging out in bars, night clubs and restaurants, as opposed to getting drunk in entrance halls and stairwells of shabby Soviet condominiums.

The same changes can be observed in individual countries. For example, with 15.76 liters per capita, Russia’s alcohol consumption in 2011 was still the fourth highest in Europe. Yet by 2013 it dropped to 13.5 liters, a level comparable with those of the European Union. Moreover, wine and beer are gradually overtaking spirits as most popular alcoholic beverages for Russian drinkers.

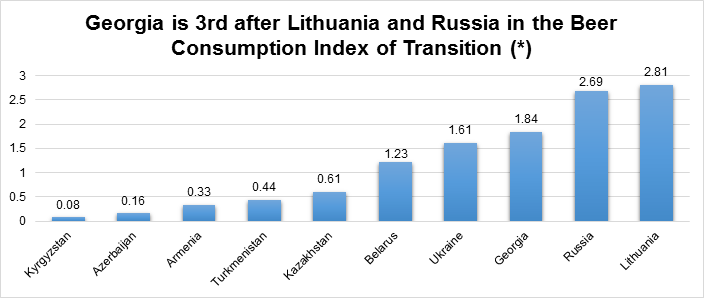

The extent to which different countries switched to beer drinking serves as a yardstick for measuring how far they have adapted to Western life styles and consumption habits. Using WHO data on the change in beer consumption between 1990 and 2011, the Beer Consumption Index of Transition from Socialism to Capitalism places Georgia third, after Lithuania (1) and Russia (2), and before Ukraine (4) and Belarus (5). Armenia and Azerbaijan – however – seem to drink far less beer. In the latter case, the predominantly Muslim religion of the country is probably the reason for the statistic.

The gradual transition to softer alcoholic drinks, as observed in the former Soviet space, is clearly a good thing. It is to be hoped that this change in consumption habits – and culture – will soon be followed by improvements in economic performance, social solidarity and governance, allowing “transition countries” to rise above consumerism and nationalism, and finally reach the promised land of prosperity and peace.

◊ ◊ ◊

The Jewish people spent forty years circling the Sinai Peninsula before being allowed into the “Promised Land”. This time was required for new generations to grow up, generations that had never known slavery, and who were accordingly less likely to acquire a recidivistic taste for the pagan deities of old, such as the Golden Calf (a biblical metaphor for unbridled self-interest and corruption?). Assuming that human nature has not fundamentally changed since Moses’ time, we may have only another 13 years to walk in the desert. But don’t hold your breath!

The main idea for this article was contributed by Laura Manukyan from ISET-PI's Social Policy Research Center, who also assisted with research and data analysis. I would also like to acknowledge Martin Smith’s help with the title, as well as his musical and painstakingly precise editorial suggestions – from which I have learned a lot!

Comments