This week, the Georgian public was shocked when a gross lack of competence and aptitude among the country’s teachers was unveiled. As DFWatch.net reports on March 10th (quoting a Georgian source), of the 10,552 teachers registered for a competence check that took place in January, only 6,477 showed up in the first place, and of these, only 1,101 passed the test. However, the Georgian economy is struck by severe deficits in knowledge and skills in many sectors, and to find such examples, one does not have to look at industries that operate close to the technological frontier.

In this two-part article, we report on the efforts of UNDP and ISET to shed light on the availability of relevant knowledge and skills in Georgian agriculture. This week, we will speak about the motivation of a study we conduct on this topic and the methodological problems that we faced so far. Next week, we will present and discuss some of our findings.

Being a farmer in Georgia is a status, not a qualification. However, the increasing importance of knowledge, skills, and competences in Georgia’s rural economy calls for professionalization. The future farmer in Georgia will have a formal qualification from a vocational school which provides the relevant knowledge and skills to run a profitable farm, gain sufficient income for his or her family, and supply high quality food to domestic and export markets. Based on such a formal qualification, the future Georgian farmer will have access to public and private extension systems (“agricultural extension systems” are providing technical and/or managerial advice to farmers, both through public authorities or private companies, which enables to deal with the challenges facing modern agri-businesses). Looking to Europe, we can identify a very clear principle: only with a formal agricultural qualification, a farmer is eligible to benefit from public support schemes and subsidies. This is where Georgian agriculture is heading.

RURAL KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS GAPS

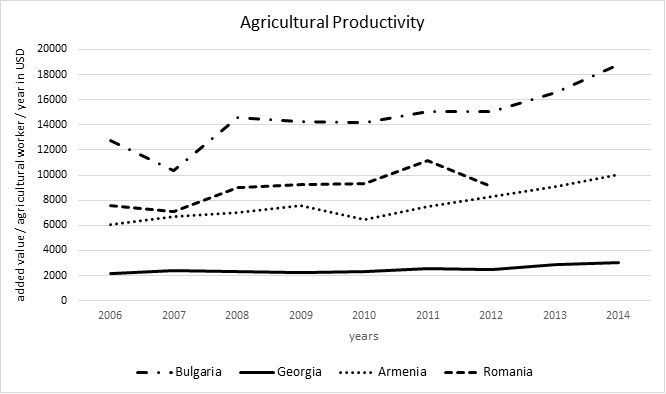

Agriculture is generally considered to be one of the sectors of the Georgian economy which has the greatest development potential. Productivity leaps seem to be overdue and are expected to occur in the next years (simply based on the fact that Georgian agricultural is extremely unproductive and improvements should be easy to achieve). However, as can be seen in the chart, these expectations were so far not even rudimentarily fulfilled: while agricultural productivity picked up in other transition countries, Georgian productivity dynamics resemble a flat line. To what extent can this disappointing outcome be explained by knowledge gaps and skill deficits of Georgian farmers?

To address this question, UNDP commissioned a survey among 3,000 Georgian rural households (within the framework of the UNDP project “Modernization of the Vocational Education and Training and Extension Systems Related to Agriculture in Georgia”, supported by the Swiss Cooperation Office South Caucasus). The survey elicited the economic statuses and performances of the respondents and requested a self-assessment of the knowledge and skills in many different agriculture-related activities. The survey focuses on the abundance or scarcity of agricultural human capital, which is a key determinant of agricultural productivity for four reasons.

Firstly, knowledge and skills are important in themselves. There is a direct impact on the output of the farm if the farmer knows when it is the best time to seed, how to prepare the soil, and how to make use of irrigation, to name just a few of those activities that require knowledge.

Secondly, knowledge is indispensable for the use of technology, which is in turn an important driver of productivity. Without operating and mechanical skills, even simple agricultural machinery cannot be used and maintained, let alone the high-tech equipment deployed in developed countries. Moreover, a lack of knowledge can turn out disastrous in a mechanized agricultural production, as it jeopardizes expensive machines and equipment.

Thirdly, skills are needed to acquire capital for investments. A bank will not hand out a credit if there are no sound recordings of production amounts, costs, and prices, which are the basis for any profitability analysis. Collecting and recording such numbers requires basic knowledge in accounting and farm management. More generally, it is no exaggeration to say that credible competence of a farmer is a precondition for any investor to provide money.

Fourthly, exploiting beneficial or coping with difficult natural conditions depends on knowledge, too. For example, the quality of soil is not an unchangeable parameter but can be improved through crop rotation and other soil fertility measures but can also be spoiled by a farmer not qualified in soil cultivation.

COPING WITH DUNNING AND KRUGER

Usually, we would expect that knowledge gaps and output are negatively correlated, i.e. the greater the reported knowledge gaps, the lower the output, and vice versa. However, in the survey we observe equally often a reverse relationship, where bigger knowledge gaps are associated with higher output. Such an apparently nonsensical correlation is in fact very common in studies that rely on self-assessments, and it is known as the Dunning-Kruger effect (Kruger and Dunning: "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77, 1999, pp. 1121–34).

Dunning and Kruger, two US psychologists, conducted an experiment in which students had to solve exercises in English grammar. Afterwards, they were supposed to estimate how well they did in comparison with the rest of the group. It turned out that those who were in the bottom quartile “grossly overestimated their abilities relative to their peers”, while those who were in the top quartile slightly underestimated themselves. Dunning and Kruger’s explanation is that the knowledge needed to assess one’s own performance is the same as the knowledge which determines the performance itself: “The skills that enable one to construct a grammatical sentence are the same skills necessary to recognize a grammatical sentence, and thus are the same skills necessary to determine if a grammatical mistake has been made”.

The Dunning-Kruger effect suggests that those Georgian farmers who have little knowledge in a certain area will often not recognize their deficits, as the recognition of the usefulness of additional knowledge requires that one knows already something about the respective activity.

As in other studies, our solution to this problem was to assume that whenever a reported knowledge gap was correlated with the output, it must affect the output negatively. If the Dunning-Kruger effect was present and the reported effect was positive, we restricted ourselves to identify that knowledge gap as performance-relevant without estimating the size of the effect.

WHY THIS STUDY?

The primary goal of UNDP is to understand which are the relevant knowledge and skills gaps of Georgian farmers. This analysis will be the basis for designing and upgrading the Georgian system of vocational education and training on the one hand, and of agricultural extension on the other hand. Yet, the data allows to analyze other urgent issues in Georgian agriculture.

For example, we will identify the characteristics that indicate the economic survival of a farm and estimate the likelihood that the operations will be discontinued. This information is not only important to direct training and extension activities to the right farmers, but also to target the right groups when it comes to social welfare measures and agricultural structure policies. We will also connect our findings with existing survey data on credit supply and default rates, relating knowledge gaps and farm characteristics to one of the most severe impediments of Georgian agriculture, namely the notorious shortage of capital.

In the continuation of this article in the next week, we will present and discuss some interesting results from the pilot report of this project.

Comments

At first glance, anyone who reads this post come up the question: how can we explain this approximately constant productivity in agricultural sector?. The answer we can find in knowledge and professionalism as you mentioned. Actually there is enough lack of knowledge in Georgian agricultural sector to explain this productivity gap at least partially, but there are farmers who really know what they are doing and doing it well. I agree the statement Being a farmer in Georgia is a status, not qualification however we cannot generalize this to all farmers. Farmers need help to extend their knowledge and if there are some of them who overestimate their awareness in agricultural it does not mean that we do not do anything. It have to be mentioned also that not only knowledge and professionalism can explain this gap. The other factor is lack of investment.

So, if we want strong agricultural sector with strong farmers who will success at least to provide domestic market with healthy products we need some strong measures to be held and again as you mentioned this measures should have sufficient outcome to increase the productivity.

Thank you for such a good article.

Dear Nodar, I certainly agree that a lack of investment is a major issue. Its just that investment is also constrained by a lack of knowledge (including business planning skills, but not only)

I completely agree to you point of view professor Livny. The lack of that knowledge as you said can be considered as the origin all of these issues in my opinion. Taking some structural changes should start from there.

Since you are talking about knowledge, this may be a good occasion to advertise that much is being done to advance that knowledge – and its catching on. Farmers do seem interested of knowledge is offered in ways thats actually useful.

https://twitter.com/HansGutbrod/status/702482430364688384

One (significant) gap is that donors seem a bit slower to catch on than the Georgian farmers themselves. So maybe this is where we should really look for the problem. (Fortunately there are a few bright spots.)

Hans, I could not agree more. Donors and governments are too conservative. They are too much focused on traditional institutions: schools, universities, colleges, etc. Also, there is too much inertia in the whole business of knowledge certification. In todays world there are much more efficient ways to acquire knowledge and skills than being lectured by a professor (regardless of age and qualification). There must also exist better ways to get ones knowledge and skills certified. In many professional areas, such as accounting and IT, certification is already a private business (I am aware of ACCA, CMA, Cisco and Microsoft certificates, but there must be many other options as well). It may only be a matter of time before privately-provided certification expands to other areas. Why does it have to be a government prerogative to certify agronomists or civil engineers? In some areas, certification would be best handled by a national certifying body; in others it can be conducted globally.

Eric, looking to the reform of vocational education and training (VET) in Georgia, I cannot confirm your statement donors and governments are too conservative. I guess, the VET reform in Georgia is much more innovative and forward looking than any other educational reform project in the country. Comparing Georgia with other countries in the region, we can see that Georgia is a front-runner, at least among the countries supported under the Torino Process. UNDP and others donors have supported the reform and will continue to do so. But I guess it is important to mention, what the reform is about and I am pleased to share with you one important document to look into: http://mes.gov.ge/uploads/1.VET%20STrategy_AP_EN.pdf

The key issue of the reform is private sector involvement. UNDP has supported the modular programme development for agricultural VET programmes since 2013 and we facilitated a process with intensive private sector participation for the definition of learning outcomes and training topics. We supported the development of a work-based learning concept which will be implemented in cooperation with the private sector as equal partner.

Please allow me one additional comment: in a way you are comparing formal education with non-formal education. I dont think that you would like to demolish formal education and I hope we are both on the same page about the needs of a qualitative formal education. The modular programme approach allows to have more targeted support for those beneficiaries who are not able or willing to attend full programmes. One major aim of the current VET reform is, to bring the non-formal and the formal education more close together to be able to address current labor market needs, especially skills development!

well, as a private sector representative (arguably with experience to share, on skills development, since we export & hold certifications) we look forward to hearing/working with UNDP and the VET programmes. We certainly would love to hear more, and participate in the partnership described above.