In the last week's Khachapuri Index column in The Financial we took a break from agriculture and focused instead on the energy sector of Georgia. While the bulk of khachapuri cost is related to home grown agricultural products, to actually cook khachapuri one has to use energy. And though the share of energy in the total cost is very low, less than 6% (15 tetri, if using gas; 16 – if using electrical oven), it does not make the sector any less interesting to discuss.

Let us begin by stating the obvious: ever since we started our Khachapuri Index survey in August 2008, the prices of energy (natural gas and electricity) have not changed, having a moderating effect on the seasonal fluctuations of the index. The reason the price of energy has not changed is very simple – both electricity and natural gas tariffs are regulated by the Georgian National Energy and Water supply Regulatory Commission (GNEWRC). While formally independent, GNEWRC heeds the friendly advice from the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. And the Ministry’s advice apparently is: keep these (politically sensitive) prices constant.

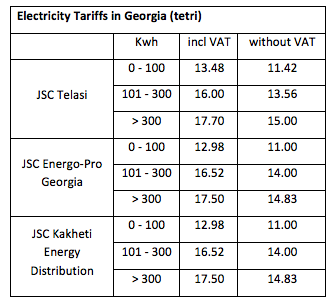

As far as electricity is concerned, there is a tiny geographic variation in tariffs (see table). In Tbilisi, where electricity is distributed by Telasi, household tariffs are a bit higher than in Kakheti (Kakheti Energy Distribution Company) and the rest of Georgia (Energo-Pro Georgia). All three companies, however, apply the same incentive scheme, whereby the more one consumes the more one pays per unit (the highest tariff is about 1/3 higher than the lowest). And all three were not allowed to change their tariffs in recent years.

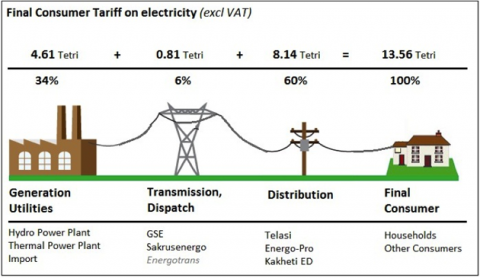

There is a long chain (actually, a cable) connecting consumers and producers of electricity in Georgia, and an interesting question is how much of the price we pay goes to which operator along this chain. Electricity travels a long distance from the generating companies (mostly hydro) through high voltage lines maintained by a state monopoly Georgian State Electrosystem (GSE) and Sakrusenergo. It arrives at the privately owned distribution monopolies: Telasi, Energo-Pro Georgia, and Kakheti Energy Distribution, and only then flows to our houses after being transformed into low voltage.

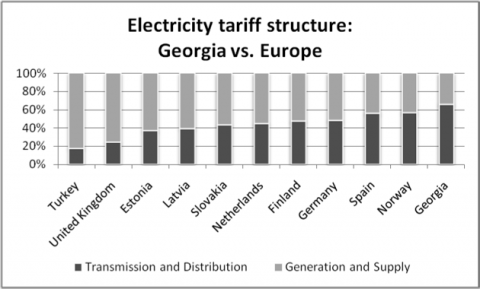

The electricity tariff we pay is allocated among these three types of actors in unequal shares. The lion’s share of the tariff, about 60%, goes to the distributors. About 34% is received by the generating companies. The smallest share, 6%, remains with the transmissions system operators. To some extent, this may be logical given that these actors face rather different costs. However, the allocation formula could also be challenged on the basis of comparison with other countries around the world. It turns out that the share of network costs (distribution and transmission) in the final price of electricity is higher in Georgia than in most European countries. On the one hand, this is easy to understand given that the bulk of Georgian generation is based on a cheap resource - water. In particular, the two largest Georgian hydropower stations, Enguri and Vardnili (both in state ownership) sell electricity at a ridiculously low tariff of less than 1.2 tetri per kWh (less than 10% of the final consumer price). And these two are responsible for between 40 and 50% of total generation! Still, Georgian distributors get a better deal than their counterparts in Norway, another hydro-based country.

Thus, the question remains whether or not the three distribution monopolies could be pushed by the regulator to operate at a lower profit margin. This question may become more pressing when additional hydropower stations become operational in a couple of years. Greater competition at the generation stage may increase the relative market power of distribution monopolies, allowing them to squeeze the new hydropower stations. However, this may not necessarily translate into lower consumer prices. For that to happen, the regulator would have to step in. Alternatively, if Georgian hydro-generators get improved access to the Turkish market, they would be in a position to negotiate higher prices and reduce the share of distribution companies in the final consumer tariff (assuming the regulator will keep it fixed).

Comments

Is there any data on the absolute cost of Transmission & Distribution, and Generation & Supply, compared to other countries? How do the percentage shares compare to countries at a similar income level as Georgia?

Yes, the data on absolute costs is available for some countries (Mainly for EU countries from Eurostat) and in vast majority of countries the absolute costs are higher compared to Georgia at both stage. For example in Romania Transmission & Distribution and Generation & Supply costs are costs are accordingly 0.05 and 0.032 Euros per kWh (2011 data). The same costs for some other countries:

Slovakia: 0.074 and 0.065 Euros

Bulgaria: 0.03 and 0.042 Euros

Cyprus: 0.036 and 0.167 Euros

Nice post! Describes in an easy ways the long way of electrons coming to our houses.

Looking to the chart, one question comes to mind: Is this supply, wholesale supply or retail sale supply?

Usually supply in electricity sector refers to retail sale supply, which is separate service from distribution. In Georgia there is only one bundled service called "distribution" which combines "lines business"(distribution) and supply activities (billing, customer service, etc.). So if this is the case, how figures will change?

I think, article seems very reasonable. Only point I would remark, is that inclusion of the energy factor in khachapuri index is a big deal , as long as food and energy products can be considered in the same category because of their high (extreme) price sensitivity. This is the possible point, which can be challenged on the basis of monthly inflation.

Yes, it is retail price. For Georgia it is not separated electricity and line service prices at distribution stage. However, if we do so it will probably decrease the share of line service cost.

Irakli: I understand that in the chart that compares Georgia and other countries the cost of supply activities (metering, billing, etc.) is subsumed under "transmission and distribution" as far as Georgia is concerned. But what about other countries? And also, what is the cost of these activities as % of final consumer price?

In the EU " transmission and distribution (Network Costs)" accounts only for electricity transfer service (at Transmission & Distribution level). All are costs are considered under "Energy (generation) and Supply" (Metering and billing service, cost of electricity and mark-up by retailers).

The official tariff (set by GNEWRC) for transferring electricity by distribution companies in Georgia is less than 1.4 tetri (with 220/380 V lines and for qualified enterprises and other distribution companies), which is about 10% of the final consumer tariff without VAT. We don't know what is this tariff for other consumers (for households for example, despite the fact that even they are eligible to buy electricity directly from small hydro power plants).

We should recall that those tariff were set five years ago. At that time distribution was unprofitable business, companies suffered from high technical/commercial losses and theft, while large investments were needed to finalize individual electricity meter instalation project and increase system efficient.

Now things have changed and distributors earn abnormal profit; further, to satisfy investors required return, new HPPs will have to set generation price at 5 $c/kwh. So we will definitely see some developemts in the market.

An excellent point! What may have been the right thing 5 years ago, may not be be justified today. I doubt GNEWRC has the expertise to determine whether or not the earlier investment in meters and distribution infrastructure has been recouped and whether the current level of profits is justified.

There is another issue to look into as well. Does the current quality of service provided by the distribution companies correspond to the level of prices they can extract from consumers? I am talking about the frequent supply interruptions, the technical quality of electricity supplied (I doubt it is of very good quality given how often I have to replace electrical bulbs in my apartment), the manner of dealing with customers. I hate the idea of being disconnected having missed the payment deadline by one day (for instance, because of a business trip or desease). Again, this may have been justified 8 or 7 years ago when it was important to eradicate the culture of non-payment and theft, but not today when everyone got used to the idea of making regular payments. Importantly, monitoring and regulating the quality of service is also the responsibility of GNEWRC.

To summarize, rules have to be reviewed and revised from time to time. In the electricity sector as well as in any other bureaucratically regulated system. However, for that to happen there has to be a crisis or protest. There is too much inertia in any bureaucracy to generate a timely change. It is much more convenient for a bureaucrat to live with the existing rules rather than to spend time and energy on trying to change them. This may be particularly difficult if there are powerful pro-status quo interests in the sector. Such as the regulated distribution monopolies.